プレプレート

石井一裕

ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学 医学部

仲嶋一範

慶應義塾大学 医学部

DOI:10.14931/bsd.7497 原稿受付日:2018年2月5日 原稿完成日:

担当編集委員:大隅 典子(東北大学 大学院医学系研究科 附属創生応用医学研究センター 脳神経科学コアセンター 発生発達神経科学分野)

英語名:preplate、同義語:primordial plexiform layer

プレプレートは、大脳皮質の発生において皮質板の出現よりも早期に髄膜と脳室帯との間に形成される薄い層構造である。発生の初期に一過的にのみ認められ、発達とともに脳表層側の辺縁帯と深層側のサブプレートに分割される。リーリンを分泌することにより大脳皮質の発生過程を制御しているカハールレチウス細胞、将来サブプレートを構成する神経細胞、コンドロイチン硫酸プロテオグリカンやフィブロネクチンなどの細胞外基質などからなる(図1)。

①カハールレチウス細胞、②将来サブプレートとなる神経細胞、③細胞外基質、④神経上皮細胞

プレプレートとは

プレプレートは、大脳皮質の発生において皮質板の出現よりも早期に髄膜と脳室帯との間に形成される薄い層構造であり、最初に最終分裂を終えた神経細胞、細胞外基質、水平方向に投射する皮質求心性線維等から構成される[1][2][3]。

マウスでは胎生11日頃からプレプレートは出現する。その後に脳室帯で誕生する神経細胞は脳表層側に放射状に移動してプレプレート内に進入する。その結果 、プレプレートは脳表層側のカハールレチウス細胞(Cajal-Retzius cell)を含む辺縁帯と深層側のサブプレートに分割され、胎生13日頃からは両者の間に皮質板と呼ばれる神経細胞層を同定できるようになる。すなわち、プレプレートと呼ばれる構造は皮質発生の初期に一過的にのみ認められるものである[4][5][6][7][8]。

構成

プレプレートは、皮質発生の最初期に最終分裂を終えた神経細胞からなり、誕生場所を異にした複数の集団から構成される。しかし、その構成要素は現在でも不明な点が多い。以下に、現在知られている構成細胞と、その他の構造物について概説する。

カハールレチウス細胞

Cajal-Retzius cell

カハールレチウス細胞は、サブプレートニューロンより早生まれであるとされている。cortical hem、ventral pallium、pallial septumを起源とし、誕生後軟膜直下を脳表面に対し平行に移動してプレプレートの一部を構成する[9]。細胞体から放射状に樹状突起を延ばし、形態的には双極性から多極性を示す[10]。また神経細胞移動や大脳皮質層形成において重要な機能分子であるリーリン(Reelin)を分泌することにより大脳皮質の発生過程を制御している[11][12]。

将来サブプレートとなる神経細胞

将来サブプレートを構成する神経細胞は、カハールレチウス細胞の産生時期に続いて脳室帯で誕生し、脳表層側に放射状に移動してプレプレートを構成する。一部の細胞はrostro-medial telencephalic wall (RMTW) からも誕生し、脳表面に平行な移動によりプレプレート内に進入するとされている[13]。

プレプレートの分割後、これらの細胞は深層側のサブプレートに配置されサブプレートニューロンと呼ばれるようになる。サブプレートニューロンは皮質板を構成する他の神経細胞よりも早期に分化するため、この時期より樹状突起形成や外套下部への軸索投射がみられる[14]。この皮質板形成初期の軸索投射をpioneer projectionと呼び、視床皮質投射の線維を皮質板にガイドする役割を担う[15]。

また、サブプレートニューロンには細胞形態や発現遺伝子が異なるものが含まれており、複数の集団から構成されると考えられている[16][17]。

マウスでは生後にサブプレートニューロンの多くはアポトーシスを起こして消失する。ただし、調べられた全ての動物種で一部の細胞は成体まで残る(第VIb層)。

また、統合失調症では白質内に異所性の神経細胞が増加することが報告されているが、そのうちのNADPHジアフォラーゼ染色により同定されるinterstitial white matter neuronは白質内に残存したサブプレートニューロンと考えられている[18]。

その他の神経細胞

ヒトにおいて、プレプレート内に抑制性アミノ酸であるγ-アミノ酪酸(γ-aminobutyric acid:GABA)と転写因子Nkx2.1または転写因子Dlxとを共発現した神経細胞の存在が報告されており、これらは大脳基底核原基(ganglionic eminence:GE)由来のGABA作動性抑制性神経細胞の特徴を持つと考えられている[19]。

従来は、大脳皮質発生期において皮質内に最初に出現する神経細胞はカハールレチウス細胞と将来サブプレートとなる細胞と考えられてきた。しかし、これらの細胞よりも早期にプレプレート内に出現する神経細胞の存在もラットで報告されている[20][21]。

また、ヒトにおいて、脳室帯で神経細胞の産生が始まるよりも前に、神経細胞マーカーであるTU20を発現するpredecessor neuronが軟膜直下に存在し、後に転写因子Tbr1を発現することが報告された。この細胞の役割に関してはまだ不明であるが、水平に伸びる長い樹状突起により軸索の投射や後続の移動細胞をガイドしていることが示唆されている[22]。

細胞外基質 (extracellular matrix)

プレプレート内には細胞成分の他に多くの細胞外基質や細胞外分泌タンパク質が含まれる。細胞外基質としてはコンドロイチン硫酸プロテオグリカン(chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans:CSPGs)やフィブロネクチン、細胞外分泌タンパク質としてはリーリンがその代表的なものである。

CSPGsはプレプレートニューロンから分泌されると考えられており、その分布はプレプレートニューロンの分布に依存する。リーリン分子を欠損したリーラーマウス(reeler)ではプレプレートの分割が起きずプレプレートニューロンが異所的に脳表面近くに分布することが知られているが(後述)、リーラーにおいてCSPGsの分布がその異所性のプレプレートニューロンの分布に一致することが、CSPGs の分布がプレプレートニューロンに依存するとされる根拠の一つである。プレプレートにおけるCSPGsの役割は、軸索形成を阻害するという他の部位で見られる機能とは異なり、視床皮質線維と皮質遠心性線維とをサブプレート直下で分離することに関与しているとの報告もある[23][24][5]が、まだ未解明な部分が多い。

その他の構造物

ネコの胎児における観察で、皮質板が出現するよりも早期に、プレプレート内を脳表面に対して平行な方向に皮質求心性線維が投射することが報告されている[25]。

ヒトでも同様にプレプレート内に皮質求心性線維の投射を認め、当初はモノアミン神経線維(monoaminergic fiber)の投射と推測された。しかし、カテコールアミン合成系酵素であるチロシン水酸化酵素(tyrosine hydroxylase:TH)による免疫染色の結果、皮質板出現後においてはTH陽性の線維を皮質第I層とサブプレートに認めたものの、プレプレート期においては認めなかったとの報告もある[26][21]。

プレプレートの分割とリーリン

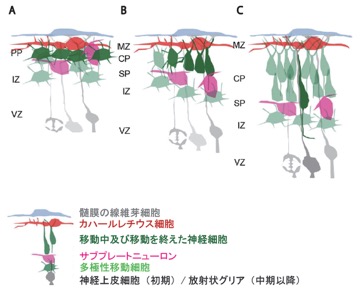

A. 将来皮質第VI層の細胞になる神経細胞が多極性移動細胞の形態をとってプレプレート内に進入する。

B. 将来皮質第VI層の細胞になる神経細胞が多極性移動細胞の形態をとった後に放射状に形態・向きを変える。それに伴いプレプレートの分割が起き、CPが出現する。

C. 後続の移動神経細胞が次々とCPに進入し、早生まれの細胞がより深層に、遅生まれの細胞がより表層に位置するinside-out様式の層構造を形成する。

PP: プレプレート (preplate)、MZ: 辺縁帯 (marginal zone)、CP: 皮質板 (cortical plate)、SP: サブプレート (subplate)、IZ: 中間帯 (intermediate zone)、VZ: 脳室帯 (ventricular zone)

[27]を改変

マウスでは胎生13日頃より、将来皮質板第VI層となる神経細胞がプレプレート内に進入する。その結果、胎生13日頃よりプレプレートの分割が起こる(図2)。

リーリンを欠損したリーラーマウスでは、プレプレートの分割が起きず軟膜直下にカハールレチウス細胞、サブプレートニューロン、一部のⅥ層ニューロン等が入り混じった層であるスーパープレートを形成する。更に後続の移動細胞はinside-out様式の層構造を形成できず層構造が概ね逆転したoutside-in構造となる[28]。

また、脳室帯に異所性にリーリンを発現させたマウスとリーラーマウスとをかけ合わせて作成したマウスでは、プレプレートの分割が部分的にレスキューされること[29]、リーリンの下流分子のグアニンヌクレオチド交換因子(guanine nucleotide exchange factor:GEF)である C3Gのノックアウトマウスではプレプレートの分割が起きないこと[30]等、プレプレートの分割にリーリンシグナルが必要であることを示唆する研究結果が多数報告されている。

関連項目

参考文献

- ↑

Marin-Padilla, M. (1971).

Early prenatal ontogenesis of the cerebral cortex (neocortex) of the cat (Felis domestica). A Golgi study. I. The primordial neocortical organization. Zeitschrift fur Anatomie und Entwicklungsgeschichte, 134(2), 117-45. [PubMed:4932608] [WorldCat] - ↑

Stewart, G.R., & Pearlman, A.L. (1987).

Fibronectin-like immunoreactivity in the developing cerebral cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 7(10), 3325-33. [PubMed:3668630] [WorldCat] - ↑

Bystron, I., Blakemore, C., & Rakic, P. (2008).

Development of the human cerebral cortex: Boulder Committee revisited. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 9(2), 110-22. [PubMed:18209730] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Caviness, V.S. (1982).

Neocortical histogenesis in normal and reeler mice: a developmental study based upon [3H]thymidine autoradiography. Brain research, 256(3), 293-302. [PubMed:7104762] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 5.0 5.1

Sheppard, A.M., & Pearlman, A.L. (1997).

Abnormal reorganization of preplate neurons and their associated extracellular matrix: an early manifestation of altered neocortical development in the reeler mutant mouse. The Journal of comparative neurology, 378(2), 173-9. [PubMed:9120058] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Rice, D.S., & Curran, T. (2001).

Role of the reelin signaling pathway in central nervous system development. Annual review of neuroscience, 24, 1005-39. [PubMed:11520926] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tissir, F., & Goffinet, A.M. (2003).

Reelin and brain development. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 4(6), 496-505. [PubMed:12778121] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 仲嶋一範

脳の発生学 第4章 ニューロンの移動と層および神経核の形成

化学同人(東京): 53-71 :2013 - ↑

Bielle, F., Griveau, A., Narboux-Nême, N., Vigneau, S., Sigrist, M., Arber, S., ..., & Pierani, A. (2005).

Multiple origins of Cajal-Retzius cells at the borders of the developing pallium. Nature neuroscience, 8(8), 1002-12. [PubMed:16041369] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Marín-Padilla, M. (1990).

Three-dimensional structural organization of layer I of the human cerebral cortex: a Golgi study. The Journal of comparative neurology, 299(1), 89-105. [PubMed:2212113] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

D'Arcangelo, G., Miao, G.G., Chen, S.C., Soares, H.D., Morgan, J.I., & Curran, T. (1995).

A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler. Nature, 374(6524), 719-23. [PubMed:7715726] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ogawa, M., Miyata, T., Nakajima, K., Yagyu, K., Seike, M., Ikenaka, K., ..., & Mikoshiba, K. (1995).

The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons. Neuron, 14(5), 899-912. [PubMed:7748558] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Pedraza, M., Hoerder-Suabedissen, A., Albert-Maestro, M.A., Molnár, Z., & De Carlos, J.A. (2014).

Extracortical origin of some murine subplate cell populations. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(23), 8613-8. [PubMed:24778253] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

McConnell, S.K., Ghosh, A., & Shatz, C.J. (1989).

Subplate neurons pioneer the first axon pathway from the cerebral cortex. Science (New York, N.Y.), 245(4921), 978-82. [PubMed:2475909] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ghosh, A., Antonini, A., McConnell, S.K., & Shatz, C.J. (1990).

Requirement for subplate neurons in the formation of thalamocortical connections. Nature, 347(6289), 179-81. [PubMed:2395469] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Oeschger, F.M., Wang, W.Z., Lee, S., García-Moreno, F., Goffinet, A.M., Arbonés, M.L., ..., & Molnár, Z. (2012).

Gene expression analysis of the embryonic subplate. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 22(6), 1343-59. [PubMed:21862448] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hoerder-Suabedissen, A., & Molnár, Z. (2015).

Development, evolution and pathology of neocortical subplate neurons. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 16(3), 133-46. [PubMed:25697157] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Akbarian, S., Bunney, W.E., Potkin, S.G., Wigal, S.B., Hagman, J.O., Sandman, C.A., & Jones, E.G. (1993).

Altered distribution of nicotinamide-adenine dinucleotide phosphate-diaphorase cells in frontal lobe of schizophrenics implies disturbances of cortical development. Archives of general psychiatry, 50(3), 169-77. [PubMed:7679891] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Rakic, S., & Zecevic, N. (2003).

Emerging complexity of layer I in human cerebral cortex. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 13(10), 1072-83. [PubMed:12967924] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Meyer, G., Soria, J.M., Martínez-Galán, J.R., Martín-Clemente, B., & Fairén, A. (1998).

Different origins and developmental histories of transient neurons in the marginal zone of the fetal and neonatal rat cortex. The Journal of comparative neurology, 397(4), 493-518. [PubMed:9699912] [WorldCat] - ↑ 21.0 21.1

Zecevic, N., Milosevic, A., Rakic, S., & Marín-Padilla, M. (1999).

Early development and composition of the human primordial plexiform layer: An immunohistochemical study. The Journal of comparative neurology, 412(2), 241-54. [PubMed:10441754] [WorldCat] - ↑

Bystron, I., Rakic, P., Molnár, Z., & Blakemore, C. (2006).

The first neurons of the human cerebral cortex. Nature neuroscience, 9(7), 880-6. [PubMed:16783367] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Bicknese, A.R., Sheppard, A.M., O'Leary, D.D., & Pearlman, A.L. (1994).

Thalamocortical axons extend along a chondroitin sulfate proteoglycan-enriched pathway coincident with the neocortical subplate and distinct from the efferent path. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 14(6), 3500-10. [PubMed:8207468] [WorldCat] - ↑

Miller, B., Sheppard, A.M., Bicknese, A.R., & Pearlman, A.L. (1995).

Chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans in the developing cerebral cortex: the distribution of neurocan distinguishes forming afferent and efferent axonal pathways. The Journal of comparative neurology, 355(4), 615-28. [PubMed:7636035] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Marin-Padilla, M. (1978).

Dual origin of the mammalian neocortex and evolution of the cortical plate. Anatomy and embryology, 152(2), 109-26. [PubMed:637312] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Zecevic, N., & Verney, C. (1995).

Development of the catecholamine neurons in human embryos and fetuses, with special emphasis on the innervation of the cerebral cortex. The Journal of comparative neurology, 351(4), 509-35. [PubMed:7721981] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Olson, E.C. (2014).

Analysis of preplate splitting and early cortical development illuminates the biology of neurological disease. Frontiers in pediatrics, 2, 121. [PubMed:25426475] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Honda, T., Kobayashi, K., Mikoshiba, K., & Nakajima, K. (2011).

Regulation of cortical neuron migration by the Reelin signaling pathway. Neurochemical research, 36(7), 1270-9. [PubMed:21253854] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Magdaleno, S., Keshvara, L., & Curran, T. (2002).

Rescue of ataxia and preplate splitting by ectopic expression of Reelin in reeler mice. Neuron, 33(4), 573-86. [PubMed:11856531] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Voss, A.K., Britto, J.M., Dixon, M.P., Sheikh, B.N., Collin, C., Tan, S.S., & Thomas, T. (2008).

C3G regulates cortical neuron migration, preplate splitting and radial glial cell attachment. Development (Cambridge, England), 135(12), 2139-49. [PubMed:18506028] [WorldCat] [DOI]