「視覚前野」の版間の差分

細 (.) |

細 (,) |

||

| 15行目: | 15行目: | ||

==視覚前野とは== | ==視覚前野とは== | ||

哺乳類の大脳新皮質の視覚野の一部で、後頭葉の視覚連合野(後頭連合野)、あるいは後頭葉から一次視覚野(V1)を除いた部分。細胞構築学的にはブロードマンの脳地図の18野、19野に相当する。18野を[[前有線皮質]]([[傍有線野]]、prestriate cortex)、19野を[[周有線皮質]]([[周線条野]]、[[後頭眼野]]、parastriate cortex)、視覚前全体野を[[外線条皮質]]([[有線外皮質]]、extrastriate cortex、circumstriate cortex)と呼ぶ。当初、一次視覚野(V1)に隣接する領域を広く視覚前野ないし視覚連合野と称した。1960年代以降、ニューロンの発火活動や神経投射の研究により、ニューロンの応答特性、受容野の大きさや位置、ニューロン間の結合関係に着目した機能的な領野の区分が[[wikipedia:ja:ネコ|ネコ]]や[[wikipedia:ja:ネコ|サル]]で盛んになった。また[[免疫組織化学]]的な[[染色法]] | 哺乳類の大脳新皮質の視覚野の一部で、後頭葉の視覚連合野(後頭連合野)、あるいは後頭葉から一次視覚野(V1)を除いた部分。細胞構築学的にはブロードマンの脳地図の18野、19野に相当する。18野を[[前有線皮質]]([[傍有線野]]、prestriate cortex)、19野を[[周有線皮質]]([[周線条野]]、[[後頭眼野]]、parastriate cortex)、視覚前全体野を[[外線条皮質]]([[有線外皮質]]、extrastriate cortex、circumstriate cortex)と呼ぶ。当初、一次視覚野(V1)に隣接する領域を広く視覚前野ないし視覚連合野と称した。1960年代以降、ニューロンの発火活動や神経投射の研究により、ニューロンの応答特性、受容野の大きさや位置、ニューロン間の結合関係に着目した機能的な領野の区分が[[wikipedia:ja:ネコ|ネコ]]や[[wikipedia:ja:ネコ|サル]]で盛んになった。また[[免疫組織化学]]的な[[染色法]]の進歩による細胞構築学的な研究も進んだ。1980年代以降、[[fMRI]]や[[光計測]]等の発達により視野地図の広がりの可視化(イメージング)する研究が進んだ。現在ではV2、V3、V4、V5/MT、V6等の機能的な領野が同定され、個別の領野として扱われることが多い。機能的な領野区分はマカカ属サル([[wikipedia:ja:アカゲザル|アカゲザル]]、[[wikipedia:ja:ニホンザル|ニホンザル]]など)で最も進んでいるが、細部や高次領域(V3、V4、V6)については研究者間で見解の相違がある。動物種によっても区分法や名称が異なる。 | ||

==機能的な領野の区分== | ==機能的な領野の区分== | ||

| 23行目: | 23行目: | ||

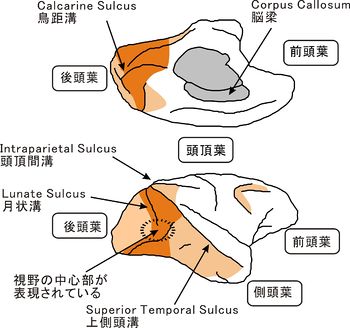

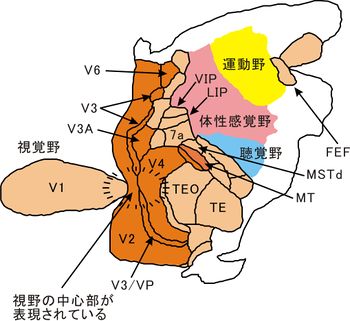

[[Image:視覚前野図4-2.jpg|400px|thumb|350px|'''図2.マカカ属サルの大脳皮質の展開図(右半球)'''<br>大脳皮質の表面をのばして表示したもので、内側で切って上下に開いたように表示してある。右側が前頭葉(前側)、左側が後頭葉(後側)。橙色の部分が視覚前野、肌色がその他の視覚野を示す。(Felleman and Van Essen (1991)<ref name=ref4><pubmed>1822724</pubmed></ref> Fig.2を改変)]] | [[Image:視覚前野図4-2.jpg|400px|thumb|350px|'''図2.マカカ属サルの大脳皮質の展開図(右半球)'''<br>大脳皮質の表面をのばして表示したもので、内側で切って上下に開いたように表示してある。右側が前頭葉(前側)、左側が後頭葉(後側)。橙色の部分が視覚前野、肌色がその他の視覚野を示す。(Felleman and Van Essen (1991)<ref name=ref4><pubmed>1822724</pubmed></ref> Fig.2を改変)]] | ||

V1と同様に、視覚前野のニューロンは(古典的)受容野より視覚入力を受け、レチノトピー(網膜部位の再現)の性質を示す(詳細は受容野を参照)。片半球の1つの機能的な領野は反対側の視野を映す一枚のトポグラフィックな[[視野地図]]を持つ。受容野の位置が[[中心視野]](fovea)から周辺視野に移るにつれて、受容野の大きさは一定の割合で大きくなる。マカカ属サルのV2、V3、V4はV1の前方に帯状に広がり、大脳皮質の腹側の領域が反対側の視野の上半分(上視野)を表し、背側の領域が視野の下半分(下視野)を表し、その間の領域が[[中心視野]](fovea)を表す。V1、V2、V3、V4の[[中心視野]](fovea)を表す領域は[[月状溝]](lunate sulcus)の終端部付近に収束している。この付近では受容野が小さくその差違が明瞭でないので、これらの領域の境界を詳細に定めることが難しい。V2、V3の大部分が月状溝内部にある。V3は腹側と背側の2つの領域に分かれるとする説もある(後述。V3の項を参照)。領野の境界は視野の垂直子午線(vertical meridian)ないし水平子午線(horizontal meridian)を表す。垂直子午線付近のニューロンは[[脳梁]]を介する反対側の半球から入力を受け、両側の視野にまたがる受容野を持つ。V5/MTは上側頭溝(superior temporal sulcus、STS)内部に、V6は頭頂後頭溝内部にあり、上視野と下視野が連続した一枚の視野地図を持つ。非侵襲的な計測法(fMRI)の発展により、視野地図のイメージングによるヒトの領野区分が進んだ。V1、V2、V5/MTのようなマカカ属サルと相同な領野(ホモログ)が同定されているが、V3、V4、V6等の高次領域については諸説ある(後述。V3、V4、V6の項を参照)。ネコや[[wikipedia:ja:フェレット|フェレット]]ではV1、V2、V3をそのまま17野、18野、19野と呼ぶことが一般的である<ref><pubmed>8439738</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>11884357</pubmed></ref>。ネコやフェレットの高次領域の区分は確立されていない。サルの視覚前野がV1から主な入力を受けるのに対して、ネコやフェレットでは、[[外側膝状体]]から17野、18野、19野に並行な投射が存在する<ref><pubmed>231475</pubmed></ref>。マウスやラットの大脳皮質にもV1より高次の視覚領域が複数存在することが知られているが、個別の領野として確立されるに至っていない<ref><pubmed>1184785</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>661689</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>6776164</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>2358036</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>7690066</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>8335065</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>17366604</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

==階層的なネットワークと視覚情報の中間処理== | ==階層的なネットワークと視覚情報の中間処理== | ||

| 45行目: | 37行目: | ||

==重層的なネットワークと視覚情報の修飾== | ==重層的なネットワークと視覚情報の修飾== | ||

前項ではV1から高次視覚野へと向かうフィードフォワード投射の寄与を強調したが、視覚前野ではそれ以外の領野内の水平結合や視覚路内におけるフィードバック投射の寄与も大きく、また背側と腹側の視覚路間にも結合が存在する。そのため視覚前野の階層ネットワーク内の視覚情報は収束と拡散を繰り返し、ニューロンは受容野内に呈示された刺激特徴に反応するだけではなく、受容野周囲の視覚情報や視覚以外の情報による修飾作用を強く受けている。外側膝状体やV1と異なり、ある領野に局所的な損傷を与えても、視野に欠損(暗点)が生じない。 | |||

===非古典的受容野からの修飾=== | ===非古典的受容野からの修飾=== | ||

視覚前野のニューロンは受容野外に呈示されて視覚刺激に反応することはない。しかし、V1と同様に受容野の周囲に広がる非古典的受容野より刺激特徴に選択的な修飾作用を受けるものがある。V2のニューロンには最適刺激を受容野にまで拡大すると、むしろ反応が抑制されるものがある(周辺抑制)。一方、受容野内の刺激と受容野外の刺激を組みあわせにより、むしろ反応が増強(促通)するものもある。V2では受容野外に並ぶ線分の直列性に依存して、受容野に呈示した線分への反応が増強される(文脈依存性修飾作用、contextual modulation)<ref><pubmed>11050142</pubmed></ref>。また周辺抑制の分布が不均一なために、受容野を横切る輪郭線の形状、縞模様の変化、境界線を挟んだ図と地の向き対して選択的な反応を示すことが示されている<ref name=refb><pubmed>11967544</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>16768360</pubmed></ref><ref name=refc><pubmed>21091803</pubmed></ref>。V4やV5/MTにも最適な刺激を受容野外にまで拡大すると反応が抑制されるニューロンがあり、受容野内外の奥行きや運動の対比が強調しているとされる<ref name=ref6><pubmed>2213146</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>7479984</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>11068007</pubmed></ref>([[受容野]]を参照)。 | |||

===大局的な情報=== | ===大局的な情報=== | ||

視覚前野の様々な階層で、ニューロンは刺激全体が表す大局的な性質に対して選択性を示す。その反応は、受容野内に呈示されている視覚刺激の物理特性よりも、むしろ[[知覚]]される刺激の“見え”に近い。 | |||

====主観的輪郭==== | ====主観的輪郭==== | ||

subjective contour | subjective contour | ||

:[[wikipedia:ja:カニッツァの三角形|カニッツァの三角形]] | :[[wikipedia:ja:カニッツァの三角形|カニッツァの三角形]]や縞模様の端部では、刺激や端点の配列から存在しない面や輪郭線を知覚できる。この主観的輪郭線の傾きに選択的に反応するニューロンがV2で見つかっている<ref><pubmed>6539501</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>2723747</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>2723748</pubmed></ref>。 | ||

====境界線の帰属==== | ====境界線の帰属==== | ||

border ownership | border ownership | ||

: | :図と背景(地)の境界線は常に“図”の輪郭線として知覚される。受容野を横切る輪郭線のコントラスとの向きよりも、刺激全体が表す図と地の向きに選択的に反応するニューロンがV2で見つかっている<ref><pubmed>10964965</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>15996555</pubmed></ref>。 | ||

==== | ====逆相関ステレオグラム==== | ||

anti-correlated stereogram | anti-correlated stereogram | ||

: | :ドットパターンによりある奥行きを持つ面を表す。点刺激の輝度コントラストを左右の目で逆にすると、点刺激は見えても対応付けられず、奥行きをもった面を知覚できなくなる(両眼視差の対応問題、corresponding problem)。V2ドットパターンによりある奥行きを持つ面を表すV2、V4のニューロンで反応が減弱することが、これと合致する<ref><pubmed>12597865</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>15371518</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>17959744</pubmed></ref>。 | ||

====色の恒常性、明るさの恒常性==== | ====色の恒常性、明るさの恒常性==== | ||

2016年4月4日 (月) 17:05時点における版

伊藤南

東京医科歯科大学生体機能支援システム学分野

DOI:10.14931/bsd.3705 原稿受付日:2013年5月24日 原稿完成日:2015年月日

担当編集委員:藤田一郎(大阪大学 大学院生命機能研究科)

英語名:extrastriate cortex、circumstriate cortex 独:extrastriärer Kortex 仏:cortex extrastrié

同義語:外線条皮質、有線外皮質、後頭連合野

視覚前野(しかくぜんや)は哺乳類の大脳新皮質の視覚野の一部で、後頭葉の視覚連合野(後頭連合野)、ブロードマンの18、19野に相当する。さらにV2、V3、V3A、V4、V5/MT、V6等の機能的領野に区分される。第一次視覚野(V1、17野)より主な入力を受けて視覚情報処理を行う。各領野のニューロンは受容野を持ち、レチノトピーの性質を示して、片半球の領野が反対側の半視野を表す。これらの領野は階層的な結合関係を持ち、上の階層の領野ほど受容野が大きく、より複雑な刺激特徴や大局的な情報を抽出表現する。主に2つの視覚経路に分かれており、腹側視覚路はV2、V4を介して下側頭葉(側頭連合野)に出力し、物体の形状や物体表面の性質(明るさ、色、模様)を表し、視覚対象の認識や形状の表象に寄与する。背側皮質視覚路はV2、V3、V5/MT、V6を介して後頭頂葉(頭頂連合野)に出力し、3次元的な空間配置、空間の構造、動きを表して、眼や腕の運動制御に寄与する。

視覚前野とは

哺乳類の大脳新皮質の視覚野の一部で、後頭葉の視覚連合野(後頭連合野)、あるいは後頭葉から一次視覚野(V1)を除いた部分。細胞構築学的にはブロードマンの脳地図の18野、19野に相当する。18野を前有線皮質(傍有線野、prestriate cortex)、19野を周有線皮質(周線条野、後頭眼野、parastriate cortex)、視覚前全体野を外線条皮質(有線外皮質、extrastriate cortex、circumstriate cortex)と呼ぶ。当初、一次視覚野(V1)に隣接する領域を広く視覚前野ないし視覚連合野と称した。1960年代以降、ニューロンの発火活動や神経投射の研究により、ニューロンの応答特性、受容野の大きさや位置、ニューロン間の結合関係に着目した機能的な領野の区分がネコやサルで盛んになった。また免疫組織化学的な染色法の進歩による細胞構築学的な研究も進んだ。1980年代以降、fMRIや光計測等の発達により視野地図の広がりの可視化(イメージング)する研究が進んだ。現在ではV2、V3、V4、V5/MT、V6等の機能的な領野が同定され、個別の領野として扱われることが多い。機能的な領野区分はマカカ属サル(アカゲザル、ニホンザルなど)で最も進んでいるが、細部や高次領域(V3、V4、V6)については研究者間で見解の相違がある。動物種によっても区分法や名称が異なる。

機能的な領野の区分

大脳皮質の表面をのばして表示したもので、内側で切って上下に開いたように表示してある。右側が前頭葉(前側)、左側が後頭葉(後側)。橙色の部分が視覚前野、肌色がその他の視覚野を示す。(Felleman and Van Essen (1991)[1] Fig.2を改変)

V1と同様に、視覚前野のニューロンは(古典的)受容野より視覚入力を受け、レチノトピー(網膜部位の再現)の性質を示す(詳細は受容野を参照)。片半球の1つの機能的な領野は反対側の視野を映す一枚のトポグラフィックな視野地図を持つ。受容野の位置が中心視野(fovea)から周辺視野に移るにつれて、受容野の大きさは一定の割合で大きくなる。マカカ属サルのV2、V3、V4はV1の前方に帯状に広がり、大脳皮質の腹側の領域が反対側の視野の上半分(上視野)を表し、背側の領域が視野の下半分(下視野)を表し、その間の領域が中心視野(fovea)を表す。V1、V2、V3、V4の中心視野(fovea)を表す領域は月状溝(lunate sulcus)の終端部付近に収束している。この付近では受容野が小さくその差違が明瞭でないので、これらの領域の境界を詳細に定めることが難しい。V2、V3の大部分が月状溝内部にある。V3は腹側と背側の2つの領域に分かれるとする説もある(後述。V3の項を参照)。領野の境界は視野の垂直子午線(vertical meridian)ないし水平子午線(horizontal meridian)を表す。垂直子午線付近のニューロンは脳梁を介する反対側の半球から入力を受け、両側の視野にまたがる受容野を持つ。V5/MTは上側頭溝(superior temporal sulcus、STS)内部に、V6は頭頂後頭溝内部にあり、上視野と下視野が連続した一枚の視野地図を持つ。非侵襲的な計測法(fMRI)の発展により、視野地図のイメージングによるヒトの領野区分が進んだ。V1、V2、V5/MTのようなマカカ属サルと相同な領野(ホモログ)が同定されているが、V3、V4、V6等の高次領域については諸説ある(後述。V3、V4、V6の項を参照)。ネコやフェレットではV1、V2、V3をそのまま17野、18野、19野と呼ぶことが一般的である[2][3]。ネコやフェレットの高次領域の区分は確立されていない。サルの視覚前野がV1から主な入力を受けるのに対して、ネコやフェレットでは、外側膝状体から17野、18野、19野に並行な投射が存在する[4]。マウスやラットの大脳皮質にもV1より高次の視覚領域が複数存在することが知られているが、個別の領野として確立されるに至っていない[5][6][7][8][9][10][11]。

階層的なネットワークと視覚情報の中間処理

視覚前野の機能的な領野は階層的な結合関係を持ち、V1と高次視覚野(側頭葉、頭頂葉)の間で、視覚情報の中間処理を行う。視覚情報の流れは主に背側視覚路と腹側視覚路とに分かれる[12][13][14][15][16][17](詳細は視覚路、受容野を参照)。ニューロンは受容野に呈示される刺激の持つ特定の特徴やパラメータに反応し、刺激特徴やパラメータに対する選択性を示す。レチノトピーの性質より刺激特徴の視野上の位置は受容野の位置として表される。V1のニューロンは小さな受容野内に示された個々の刺激要素(スポットや線分)に反応するが、視覚経路の階層を上がるほど受容野のサイズが大きくなり、近傍のニューロン間で受容野が重複するようになって刺激位置の情報は徐々に失われる。V2やV4ではCOストライプやグロブ(後述。V2、V4野の項を参照)ごとに局所的な視野地図の繰り返しが生じている。一方、受容野内に広がるドットやテクスチャ(肌理、模様)が表す面に対して選択的な反応を示す。V1のニューロンは基本的な刺激特徴(色(輝度)、線の傾き、両眼視差、運動)に選択性を示すが、階層を上がるにつれて受容野内に広がる刺激全体が示す複雑な刺激特徴の組み合わせやパターンに選択性を示すようになる。

背側視覚路

外側膝状体の大細胞系(M経路)由来の入力を受け、その性質(色選択性が無い、輝度コントラスト感度が高い、時間分解能が高い、空間分解能が低い)を引き継ぐ[18][19]。色選択性を持たず、ほとんどのニューロンが運動(方向、速度)や両眼視差に選択性を示す。V2(広線条部)、V3、V5/MT、V6を介して後頭頂葉へ向う。領野間の結合は有髄線維により伝導速度が速く、ミエリン染色で濃く染まる。V1より各領野へ直接投射があり、視覚刺激の呈示開始よりニューロンの反応が生じるまでの時間(潜時)を比較しても領野間の差がほとんどない[20]。MTはドットパターンの一次元の運動方向や注視面を基準とする両眼視差に選択性を示す。その上位にあるMSTdは運動方向の変化(ドットパターンの発散、収縮、回転)に選択性を示す[21]。MST、VIP、7aへの出力はオプティカルフローのような3次元空間での動きの知覚に関与するとされる。一方、V3、V6は両眼視差の変化(3次元方向の運動)に選択性を示す。V6a、LIPへの出力は空間の立体構造や3次元空間での位置関係を表し、視線の移動や物体の把持や操作に利用される[22]。その際は、必ずしも刺激が意識されているわけではない。視覚前野では、刺激物体の動きと眼球や頭部の動きから生じる見かけの動きとはまだ区別されない(V3A、V6の一部のニューロンを除く)。

腹側視覚路

外側膝状体の大細胞系(M経路)と小細胞系(P経路)から同程度の入力を受け、さらに顆粒細胞系(K経路)由来の入力も受けて[23]、多様な刺激特徴に選択性を示す。色情報はP経路を介して専ら腹側視覚路に伝えられるが、V4ニューロンの約半数しか色選択性を示さない。高次の領野ほど潜時が遅い[20]。V2(狭線条部、線条間部)からV4を介して下側頭葉(TEO、TE)へ向う。視覚前野は傾きの変化(輪郭線の折れ曲がり(V2)、円弧、非カルテジアン図形(同心円、らせん、双曲線)、フーリエ図形などの曲線(V4))や両眼視差の変化(受容野内外の相対視差(V2、V4)[24]、3次元方向の線や平面の傾き(V3、V4))に選択性を示す。V1が輝度対比や色対比[25](色覚を参照)に反応するのに対して、特定の色相や彩度(V2、V4)[26]、平面のテクスチャやパターン(V4)に選択性を示す。下側頭葉には、複雑な輪郭線の形状、物体表面の曲面、手や顔のようなもっと複雑な刺激に選択性を示すものがある。下側頭葉への出力は物体の認識や表象(意識に上らせること)に関与するとされる[27][28][29][30]。

重層的なネットワークと視覚情報の修飾

前項ではV1から高次視覚野へと向かうフィードフォワード投射の寄与を強調したが、視覚前野ではそれ以外の領野内の水平結合や視覚路内におけるフィードバック投射の寄与も大きく、また背側と腹側の視覚路間にも結合が存在する。そのため視覚前野の階層ネットワーク内の視覚情報は収束と拡散を繰り返し、ニューロンは受容野内に呈示された刺激特徴に反応するだけではなく、受容野周囲の視覚情報や視覚以外の情報による修飾作用を強く受けている。外側膝状体やV1と異なり、ある領野に局所的な損傷を与えても、視野に欠損(暗点)が生じない。

非古典的受容野からの修飾

視覚前野のニューロンは受容野外に呈示されて視覚刺激に反応することはない。しかし、V1と同様に受容野の周囲に広がる非古典的受容野より刺激特徴に選択的な修飾作用を受けるものがある。V2のニューロンには最適刺激を受容野にまで拡大すると、むしろ反応が抑制されるものがある(周辺抑制)。一方、受容野内の刺激と受容野外の刺激を組みあわせにより、むしろ反応が増強(促通)するものもある。V2では受容野外に並ぶ線分の直列性に依存して、受容野に呈示した線分への反応が増強される(文脈依存性修飾作用、contextual modulation)[31]。また周辺抑制の分布が不均一なために、受容野を横切る輪郭線の形状、縞模様の変化、境界線を挟んだ図と地の向き対して選択的な反応を示すことが示されている[32][33][34]。V4やV5/MTにも最適な刺激を受容野外にまで拡大すると反応が抑制されるニューロンがあり、受容野内外の奥行きや運動の対比が強調しているとされる[35][36][37](受容野を参照)。

大局的な情報

視覚前野の様々な階層で、ニューロンは刺激全体が表す大局的な性質に対して選択性を示す。その反応は、受容野内に呈示されている視覚刺激の物理特性よりも、むしろ知覚される刺激の“見え”に近い。

主観的輪郭

subjective contour

境界線の帰属

border ownership

- 図と背景(地)の境界線は常に“図”の輪郭線として知覚される。受容野を横切る輪郭線のコントラスとの向きよりも、刺激全体が表す図と地の向きに選択的に反応するニューロンがV2で見つかっている[41][42]。

逆相関ステレオグラム

anti-correlated stereogram

- ドットパターンによりある奥行きを持つ面を表す。点刺激の輝度コントラストを左右の目で逆にすると、点刺激は見えても対応付けられず、奥行きをもった面を知覚できなくなる(両眼視差の対応問題、corresponding problem)。V2ドットパターンによりある奥行きを持つ面を表すV2、V4のニューロンで反応が減弱することが、これと合致する[43][44][45]。

色の恒常性、明るさの恒常性

- 刺激の波長成分は視覚刺激の反射特性と照明光により決まるが、モンドリアンのように受容野の周囲に異なる色の刺激を同時に呈示すると、照明条件によらない色相や輝度への選択性を示すものがV4に見つかっている[46]。

窓問題

aperture problem

- 線や縞模様の端点を隠すと、実際の運動方向ではなく、運動速度の最も低い法線方向への運動が知覚される[47]。一方、縞模様が長方形の枠内を動くと、長辺沿いの端点の動きを運動方向として知覚する(バーバーポール錯視)。MTには法線方向の動きよりも受容野外の枠沿いの端点の運動方向に選択性を示すものがある[48]。

格子模様

plaid pattern

- 傾きの異なる縞模様を重ねて動かすと、各縞に対する法線方向の動きが合成されて、格子模様が一方向に動いて見える。MTには格子模様の運動方向に選択性を示すものがある。さらに両眼視差により縞模様がすれ違うように見せたり、縞の重複部分の輝度を調整して半透明の縞模様が重なるように見せると、縞の法線方向に選択的に反応する[49][50][51]。

注意や予測(期待)

我々の視覚情報処理は視覚情報以外の能動的な修飾作用を受けている(空間的注意、選択的注意を参照)。サルを訓練して、特定の場所、刺激物体、色や形などの刺激属性に注意を向けさせた状態で記録すると反応の増強(ゲイン)、刺激選択性の向上(応答特性)、受容野の縮小や移動(空間特性)が観察される[52][53]。顕著な作用がMT[54][55][56][57]やV4[58][59][60][61]で見られる一方で、V1、V2ではそうした修飾作用は弱い[62][63]。V4では注意を向けさせると電気活動の同期性が高まることが報告されている[64]。ヒトでも同様の作用が報告されている[65]。

知覚の神経メカニズム

ある領野の電気活動が特定の視知覚の神経メカニズム(neural correlates)であることを示すには、大局的な情報に選択性を示すことだけでは不十分であり、そうした試みはあまり成功していない。MTの性質は、そうした因果関係をMTで検証することを例外的に可能にしている。

- 大多数のニューロンが運動方向や両眼視差に選択性を示す。

- 同様の選択性を持つニューロンが機能的コラムに集中している。

- 結果的に運動視や立体視が一群のニューロンの活動に依存している。

運動からの構造の知覚

structure from motion

円筒の表面に貼り付けたドットパターンが回転するように、平面上のドットを左右に動かすと回転する円筒に見える。サルを強制選択課題で訓練すると、サルにとっての回転方向の見えを評価できる。両眼視差の情報がないので見かけの回転方向が不定期に変化するが、それと同期して反応が変化するニューロンがMTで見つかった[66]。

ドットパターンの運動方向・奥行きの知覚

ドットパターンの各要素がランダムに動く中で、同じ運動方向や奥行きを持つ要素の割合(コーヒーレンス)が高い程、その検出が容易となる。サルを強制選択課題で訓練すると、刺激のコーヒーレンスと正答率には一定の相関関係があり、サルにとっての運動の見えを評価できる。

- ニューロンの発火頻度と運動の見えが相関すること、

- 一群のニューロンを破壊、麻痺、局所刺激して正答率を操作できること、

- まったくランダムな刺激に対する動物個体の知覚判断の試行間変動が発火頻度の変動と相関する(choice-probability)こと

から、比較的少数のMTニューロンの活動が運動方向の知覚を左右することが示された[67][68][69]。さらに、MTの局所電気刺激による動物の知覚判断への影響を調べた実験から、奥行き知覚とMTニューロンの活動との因果関係が示された[70]。

視覚情報処理のメカニズム

各機能的領野における視覚情報処理を解明するには、ニューロン群の結合関係や反応特性の研究に加えて、数理モデルによる定量的な解析が必要である。すでにV1では様々な数理モデルが提案されている(視差エネルギーモデルを参照)。最近、視覚前野でもこうした解析が盛んになってきた。例えば、視覚刺激の物理特性とニューロンの反応特性の関係の代わりに、直近の領野間の反応特性の関係に着目した、線形加算型の数理モデルが幾つか提案されている。V1の出力を線形加算するモデルがV2[71][32][34]やV5[72][73]のニューロンの反応選択性を説明できることが示されている。これらのモデルでは刺激要素の連続した組み合わせ(輪郭線)に対する反応が、個々の刺激要素(線分)の空間的な配置や組み合わせ方により説明されている。一方、面状に広がる刺激(ドットパターン、テクスチャや自然画像)に対する反応は、刺激に含まれる刺激要素の量により説明されている。より高次の領野でも、輪郭線の形状が刺激要素の組み合わせの線形加算により説明されるモデルがV4や[74][75][76]、IT野[77][78]で提案されている。しかし、自然画像のような面状に広がる刺激に対してはモデルの説明が十分でないとされている[79][80]。データの蓄積にともない、今後も数理モデルによる視覚情報処理メカニズムの解析が進展することが期待される。

各領野の解剖学的特徴とその機能

V2野

18野の一部。V1の主な出力先で、V1から主な入力を受け、V1 へ強いフィードバック投射する。V3、V4、V5へ出力する。チトクローム酸化酵素(CO)の染色によりCOトライプと呼ばれる領域に区分される[81][82][83]。

広線条領域(thick stripe)はV1(4b層)より大細胞系の入力を受け、V3、MTに投射する。運動方向、速度、両眼視差に選択性を示し、背側視覚路に属する。

狭線条領域(thin stripe)はV1(ブロブ)より入力を受けV4に投射する。色相に選択性を示し、腹側視覚路に属する。

線条間領域(淡線条領域)(inter stripe、pale stripe)はV1(2/3層のブロブ間)より小細胞系の入力を受け、V4に投射する。線の傾きやエンドストップ抑制により端点を表す。腹側視覚路に属する。これらの領域はV2内に縞状に交互に分布する。

V1よりも低い空間周波数成分によく反応し、両眼視差に選択性を示すニューロンが多い。大局的な選択性を示す(主観的輪郭線の傾き、輪郭線を挟んだ図と地の向き、負相関ステレオグラム)。奥行き段差による境界線の傾き[32]、受容野を横切る輪郭線の折れ曲がり[84][85]、傾きや周波数成分の異なる縞模様の組み合わせ[86]に選択性を示す。

V3野

18野の一部。背側部(V3d)と腹側部(V3v)に2分される。合わせて一つのV3とする説[87][88]と、異なる領野とする説[89]がある。V3vはVP野(腹側後部領域、ventral posterior area)とも言う[90][91][92][18]。V2(狭線条部、線条間部)から入力を受け、下側頭葉に投射する。視野の下半分を表す。色選択性を示し、腹側視覚路に属する。一方、V3dはV2(広線条部)とV1(4b層)から入力を受け、V3a、V4、V5、V6と後頭頂葉に出力する。視野の上半分を表す。ミエリン染色で濃く染まり、輝度や奥行きに選択性を示すが、色には選択性を示さない。背側皮質視覚路に属する。広域的な動きや奥行き方向の傾き、テクスチャの充填(欠損部の補完)[93]に関わる。

V2とV4の間の領域を3次視覚皮質複合体と言う。ヒトでよく発達しており、サルとの違いが顕著な領域である。V3AはV3d前方に隣接し、別の視野地図をもつ領野である。V1、V2、V3dより入力を受け、MT、MST、LIPへ出力する。サルでは、V3dに比べて速度や奥行きに選択性を示すニューロンが少なく、ドットパターンよりも線刺激に強く反応する。注意の効果が顕著に見られる[94]。視線の向きによらずに、頭部の向きを基準とする方向に選択性を示すものがある[95]。ヒトでは、むしろV3dよりもV3Aの方が運動刺激によく反応し、V3Aに経頭蓋電気刺激(TMS)を与えると速度の知覚が障害される[96]。さらに別な領域(V3B)も存在する[97][98]。

V4野

新世界ザルの背外側野(DL)に相当する。V2(狭線条部、線条間部)、V3、V3aから強い入力を受け、下側頭葉(TEO、TE)、上側頭溝(MT、MST、FST、V4t)、頭頂葉(DP、VIP、LIP、PIP、MST)、前頭葉(FEF)へ出力する。V1、V2、V3にフィードバック投射を返す。中心視の領域がV2の主な投射先であり、V1からも入力を受ける。周辺視の領域はV3、V5から強い入力を受け、上側頭溝や頭頂葉からも広く入力を受ける。背側視覚路に属する。ヒトのV4の区分には諸説がある[99][100]。

1970年代に色に選択的な領域として同定された際には、色恒常性を示すことから色表現の中枢とされた[87]</ref>[101]。1980年代になると輪郭線の形状に選択性を示すことが明らかにされた[102][35][103]。近年、色と形のサブ領域(グロブ)に分かれることが示されている[104][105]。曲線の曲率と傾き[106][74]、縞模様の空間周波数成分と傾き、輪郭線の形状に複雑な応答特性を示す。3次元方向の線の傾き[107]、受容野内外の相対的な奥行き(fine stereopsis)[108]に選択性を示す。大局的な選択性を示す(色恒常性、負相関ステレオグラム)。注意により強い修飾を受ける。

サルのV4を破壊すると、大きさの変化、遮蔽、色恒常性、主観的輪郭線に対応できなくなる、混在している複数の刺激を区別することができなくなる、同一物体の持つ奥行き,明暗,色,位置などの情報を同一物体のものとして関連付けることができなくなる[109][110][111][112]。ヒトのV8が損傷を受けると色覚だけが失われる。このV8をV4の一部とする説と、サルのTEOに相当する領域とする説がある[113][114][115][100]。

MT/V5野

運動方向に選択性をもつ領域(V5)とミエリン染色で濃く染まる領域(MT野、middle temporal area)として別々に同定されたが、後に同じ領域であることが明かにされた[116][117]。チトクローム酸化酵素[118]やCat301抗体[119]で濃く染まる。ヒトでは、隣接する領域(MST等)と合わせて、MT complex、hMT、MT+、V5と呼ぶことが多い[120][121]。背側視覚路に属し、主にV1(4b層)より、他にV2(広線条部)、V1(6層)、V3背側部、V4、V6から入力を受ける[1][122]。周辺視の領域は皮質正中部と脳梁膨大後部からも入力を受ける[123]。主に隣接するMST、FST、V4tへ、他に前頭眼野(FEF)、外側頭頂間野(LIP、VIP)、上丘(SC)へ出力を投射する。また、V1を介さない外側膝状体、視床枕からの直接入力がある[124](盲視を参照)。

大部分(70-85%)のニューロンが刺激の運動方向、速度、両眼視差に選択性を示し[117][125][126]、運動方向と両眼視差の機能的コラム(V1を参照)が存在する[127][49][128]。注視面からの絶対視差(coarse stereopsis)に選択性を示し、反射性輻輳眼球運動の生成に関与するとされる。奥行きの異なる面を区別し、運動視差(奥行きの違いにより生じる運動速度や運動方向の変化)に選択性を示す。運動方向の違いによる境界線に選択性を示す。注意により強い修飾を受ける。サルのMTは運動視や立体視に直接関わる(知覚の神経メカニズムの項を参照)。

ヒトのV5が損傷されると、運動刺激が引き起こす眼球運動が障害され、運動を知覚できずに世界が静的な"フレーム"の連続に感じられる[129][130][131]。MTに経頭蓋磁気刺激を与えると運動知覚が阻害される[132]。一方、3次元的な位置の知覚の阻害は後頭頂葉の損傷による。

V6野

新世界ザルの背内側野(DM)に相当する。当初、ヒトや旧世界ザル(マカカ属サル)には存在しないとされていた。19野の一部で、解剖学的には上頭頂小葉(PO)の一部を占める[133][134][135]。主にMTより入力を受け、隣接するV6Aに出力する。頭頂葉(MST、MIP、VIP、LIP)へも投射する。周辺視によく反応する。エンドストップ抑制が弱く、低空間周波数成分に反応する。ドットパターンよりも大きな物体の輪郭線の運動に反応するが、最適な運動方向とその逆方向を区別しない。物体の動きよりも自己運動の検出に関わるとされる。ミエリン染色で濃く染まる[136]。

関連項目

参考文献

- ↑ 1.0 1.1

Felleman, D.J., & Van Essen, D.C. (1991).

Distributed hierarchical processing in the primate cerebral cortex. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 1(1), 1-47. [PubMed:1822724] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Payne, B.R. (1993).

Evidence for visual cortical area homologs in cat and macaque monkey. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 3(1), 1-25. [PubMed:8439738] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Manger, P.R., Kiper, D., Masiello, I., Murillo, L., Tettoni, L., Hunyadi, Z., & Innocenti, G.M. (2002).

The representation of the visual field in three extrastriate areas of the ferret (Mustela putorius) and the relationship of retinotopy and field boundaries to callosal connectivity. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 12(4), 423-37. [PubMed:11884357] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Stone, J., Dreher, B., & Leventhal, A. (1979).

Hierarchical and parallel mechanisms in the organization of visual cortex. Brain research, 180(3), 345-94. [PubMed:231475] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Caviness, V.S. (1975).

Architectonic map of neocortex of the normal mouse. The Journal of comparative neurology, 164(2), 247-63. [PubMed:1184785] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Schnagl, R.D., Holmes, I.H., & Mackay-Scollay, E.M. (1978).

Coronavirus-like particles in Aboriginals and non-Aboriginals in Western Australia. The Medical journal of Australia, 1(6), 307-9. [PubMed:661689] [WorldCat] - ↑

Wagor, E., Mangini, N.J., & Pearlman, A.L. (1980).

Retinotopic organization of striate and extrastriate visual cortex in the mouse. The Journal of comparative neurology, 193(1), 187-202. [PubMed:6776164] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Coogan, T.A., & Burkhalter, A. (1990).

Conserved patterns of cortico-cortical connections define areal hierarchy in rat visual cortex. Experimental brain research, 80(1), 49-53. [PubMed:2358036] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Coogan, T.A., & Burkhalter, A. (1993).

Hierarchical organization of areas in rat visual cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 13(9), 3749-72. [PubMed:7690066] [WorldCat] - ↑

Montero, V.M. (1993).

Retinotopy of cortical connections between the striate cortex and extrastriate visual areas in the rat. Experimental brain research, 94(1), 1-15. [PubMed:8335065] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Wang, Q., & Burkhalter, A. (2007).

Area map of mouse visual cortex. The Journal of comparative neurology, 502(3), 339-57. [PubMed:17366604] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ L G Ungerleider, M Mishkin

Two cortical visual systems.

Analysis of Visual Behavior (D J Ingle, M A Goodale, R J W Masfield, eds.), MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1982. - ↑

DeYoe, E.A., & Van Essen, D.C. (1988).

Concurrent processing streams in monkey visual cortex. Trends in neurosciences, 11(5), 219-26. [PubMed:2471327] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Gattass, R., Rosa, M.G., Sousa, A.P., Piñon, M.C., Fiorani Júnior, M., & Neuenschwander, S. (1990).

Cortical streams of visual information processing in primates. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas, 23(5), 375-93. [PubMed:1965642] [WorldCat] - ↑

Baizer, J.S., Ungerleider, L.G., & Desimone, R. (1991).

Organization of visual inputs to the inferior temporal and posterior parietal cortex in macaques. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 11(1), 168-90. [PubMed:1702462] [WorldCat] - ↑

Van Essen, D.C., Anderson, C.H., & Felleman, D.J. (1992).

Information processing in the primate visual system: an integrated systems perspective. Science (New York, N.Y.), 255(5043), 419-23. [PubMed:1734518] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ungerleider, L.G., & Haxby, J.V. (1994).

'What' and 'where' in the human brain. Current opinion in neurobiology, 4(2), 157-65. [PubMed:8038571] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 18.0 18.1

Burkhalter, A., & Van Essen, D.C. (1986).

Processing of color, form and disparity information in visual areas VP and V2 of ventral extrastriate cortex in the macaque monkey. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 6(8), 2327-51. [PubMed:3746412] [WorldCat] - ↑

Levitt, J.B., Kiper, D.C., & Movshon, J.A. (1994).

Receptive fields and functional architecture of macaque V2. Journal of neurophysiology, 71(6), 2517-42. [PubMed:7931532] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 20.0 20.1

Schmolesky, M.T., Wang, Y., Hanes, D.P., Thompson, K.G., Leutgeb, S., Schall, J.D., & Leventhal, A.G. (1998).

Signal timing across the macaque visual system. Journal of neurophysiology, 79(6), 3272-8. [PubMed:9636126] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Vaina, L.M. (1998).

Complex motion perception and its deficits. Current opinion in neurobiology, 8(4), 494-502. [PubMed:9751663] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Taira, M., Tsutsui, K.I., Jiang, M., Yara, K., & Sakata, H. (2000).

Parietal neurons represent surface orientation from the gradient of binocular disparity. Journal of neurophysiology, 83(5), 3140-6. [PubMed:10805708] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Maunsell, J.H. (1992).

Functional visual streams. Current opinion in neurobiology, 2(4), 506-10. [PubMed:1525550] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Uka, T., Tanaka, H., Yoshiyama, K., Kato, M., & Fujita, I. (2000).

Disparity selectivity of neurons in monkey inferior temporal cortex. Journal of neurophysiology, 84(1), 120-32. [PubMed:10899190] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Dacey, D.M. (1999).

Primate retina: cell types, circuits and color opponency. Progress in retinal and eye research, 18(6), 737-63. [PubMed:10530750] [WorldCat] - ↑

Xiao, Y., Wang, Y., & Felleman, D.J. (2003).

A spatially organized representation of colour in macaque cortical area V2. Nature, 421(6922), 535-9. [PubMed:12556893] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Desimone, R., Albright, T.D., Gross, C.G., & Bruce, C. (1984).

Stimulus-selective properties of inferior temporal neurons in the macaque. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 4(8), 2051-62. [PubMed:6470767] [WorldCat] - ↑

Fujita, I., Tanaka, K., Ito, M., & Cheng, K. (1992).

Columns for visual features of objects in monkey inferotemporal cortex. Nature, 360(6402), 343-6. [PubMed:1448150] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Kobatake, E., & Tanaka, K. (1994).

Neuronal selectivities to complex object features in the ventral visual pathway of the macaque cerebral cortex. Journal of neurophysiology, 71(3), 856-67. [PubMed:8201425] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hegdé, J., & Van Essen, D.C. (2007).

A comparative study of shape representation in macaque visual areas v2 and v4. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 17(5), 1100-16. [PubMed:16785255] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Bakin, J.S., Nakayama, K., & Gilbert, C.D. (2000).

Visual responses in monkey areas V1 and V2 to three-dimensional surface configurations. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 20(21), 8188-98. [PubMed:11050142] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2

Thomas, O.M., Cumming, B.G., & Parker, A.J. (2002).

A specialization for relative disparity in V2. Nature neuroscience, 5(5), 472-8. [PubMed:11967544] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Sakai, K., & Nishimura, H. (2006).

Surrounding suppression and facilitation in the determination of border ownership. Journal of cognitive neuroscience, 18(4), 562-79. [PubMed:16768360] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 34.0 34.1

Ito, M., & Goda, N. (2011).

Mechanisms underlying the representation of angles embedded within contour stimuli in area V2 of macaque monkeys. The European journal of neuroscience, 33(1), 130-42. [PubMed:21091803] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 35.0 35.1

Schein, S.J., & Desimone, R. (1990).

Spectral properties of V4 neurons in the macaque. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 10(10), 3369-89. [PubMed:2213146] [WorldCat] - ↑

Xiao, D.K., Raiguel, S., Marcar, V., Koenderink, J., & Orban, G.A. (1995).

Spatial heterogeneity of inhibitory surrounds in the middle temporal visual area. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 92(24), 11303-6. [PubMed:7479984] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Born, R.T. (2000).

Center-surround interactions in the middle temporal visual area of the owl monkey. Journal of neurophysiology, 84(5), 2658-69. [PubMed:11068007] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

von der Heydt, R., Peterhans, E., & Baumgartner, G. (1984).

Illusory contours and cortical neuron responses. Science (New York, N.Y.), 224(4654), 1260-2. [PubMed:6539501] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

von der Heydt, R., & Peterhans, E. (1989).

Mechanisms of contour perception in monkey visual cortex. I. Lines of pattern discontinuity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 9(5), 1731-48. [PubMed:2723747] [WorldCat] - ↑

Peterhans, E., & von der Heydt, R. (1989).

Mechanisms of contour perception in monkey visual cortex. II. Contours bridging gaps. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 9(5), 1749-63. [PubMed:2723748] [WorldCat] - ↑

Zhou, H., Friedman, H.S., & von der Heydt, R. (2000).

Coding of border ownership in monkey visual cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 20(17), 6594-611. [PubMed:10964965] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Qiu, F.T., & von der Heydt, R. (2005).

Figure and ground in the visual cortex: v2 combines stereoscopic cues with gestalt rules. Neuron, 47(1), 155-66. [PubMed:15996555] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Janssen, P., Vogels, R., Liu, Y., & Orban, G.A. (2003).

At least at the level of inferior temporal cortex, the stereo correspondence problem is solved. Neuron, 37(4), 693-701. [PubMed:12597865] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tanabe, S., Umeda, K., & Fujita, I. (2004).

Rejection of false matches for binocular correspondence in macaque visual cortical area V4. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 24(37), 8170-80. [PubMed:15371518] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Kumano, H., Tanabe, S., & Fujita, I. (2008).

Spatial frequency integration for binocular correspondence in macaque area V4. Journal of neurophysiology, 99(1), 402-8. [PubMed:17959744] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Zeki, S. (1983).

The distribution of wavelength and orientation selective cells in different areas of monkey visual cortex. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 217(1209), 449-70. [PubMed:6134287] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ J A Movshon, E H Adelson, M S Gizzi, W T Newsome

The analysis of moving visual patterns.

Study Group on Pattern Recognition Mechanisms (C Chagas, R Gattas, C Gross, eds. Vatican City: Pontifica Academia Scientiarum, pp.117-151,1985. - ↑

Pack, C.C., Gartland, A.J., & Born, R.T. (2004).

Integration of Contour and Terminator Signals in Visual Area MT of Alert Macaque. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 24(13), 3268-80. [PubMed:15056706] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 49.0 49.1

Albright, T.D. (1984).

Direction and orientation selectivity of neurons in visual area MT of the macaque. Journal of neurophysiology, 52(6), 1106-30. [PubMed:6520628] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Rodman, H.R., & Albright, T.D. (1987).

Coding of visual stimulus velocity in area MT of the macaque. Vision research, 27(12), 2035-48. [PubMed:3447355] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Stoner, G.R., & Albright, T.D. (1992).

Neural correlates of perceptual motion coherence. Nature, 358(6385), 412-4. [PubMed:1641024] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Desimone, R., & Duncan, J. (1995).

Neural mechanisms of selective visual attention. Annual review of neuroscience, 18, 193-222. [PubMed:7605061] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Maunsell, J.H., & Cook, E.P. (2002).

The role of attention in visual processing. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 357(1424), 1063-72. [PubMed:12217174] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Treue, S., & Maunsell, J.H. (1996).

Attentional modulation of visual motion processing in cortical areas MT and MST. Nature, 382(6591), 539-41. [PubMed:8700227] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Treue, S., & Martínez Trujillo, J.C. (1999).

Feature-based attention influences motion processing gain in macaque visual cortex. Nature, 399(6736), 575-9. [PubMed:10376597] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Treue, S., & Maunsell, J.H. (1999).

Effects of attention on the processing of motion in macaque middle temporal and medial superior temporal visual cortical areas. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 19(17), 7591-602. [PubMed:10460265] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Seidemann, E., & Newsome, W.T. (1999).

Effect of spatial attention on the responses of area MT neurons. Journal of neurophysiology, 81(4), 1783-94. [PubMed:10200212] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Moran, J., & Desimone, R. (1985).

Selective attention gates visual processing in the extrastriate cortex. Science (New York, N.Y.), 229(4715), 782-4. [PubMed:4023713] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Connor, C.E., Preddie, D.C., Gallant, J.L., & Van Essen, D.C. (1997).

Spatial attention effects in macaque area V4. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 17(9), 3201-14. [PubMed:9096154] [WorldCat] - ↑

McAdams, C.J., & Maunsell, J.H. (1999).

Effects of attention on orientation-tuning functions of single neurons in macaque cortical area V4. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 19(1), 431-41. [PubMed:9870971] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Reynolds, J.H., Pasternak, T., & Desimone, R. (2000).

Attention increases sensitivity of V4 neurons. Neuron, 26(3), 703-14. [PubMed:10896165] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Luck, S.J., Chelazzi, L., Hillyard, S.A., & Desimone, R. (1997).

Neural mechanisms of spatial selective attention in areas V1, V2, and V4 of macaque visual cortex. Journal of neurophysiology, 77(1), 24-42. [PubMed:9120566] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Reynolds, J.H., Chelazzi, L., & Desimone, R. (1999).

Competitive mechanisms subserve attention in macaque areas V2 and V4. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 19(5), 1736-53. [PubMed:10024360] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Fries, P., Reynolds, J.H., Rorie, A.E., & Desimone, R. (2001).

Modulation of oscillatory neuronal synchronization by selective visual attention. Science (New York, N.Y.), 291(5508), 1560-3. [PubMed:11222864] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Kastner, S., De Weerd, P., Desimone, R., & Ungerleider, L.G. (1998).

Mechanisms of directed attention in the human extrastriate cortex as revealed by functional MRI. Science (New York, N.Y.), 282(5386), 108-11. [PubMed:9756472] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Bradley, D.C., Chang, G.C., & Andersen, R.A. (1998).

Encoding of three-dimensional structure-from-motion by primate area MT neurons. Nature, 392(6677), 714-7. [PubMed:9565031] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Britten, K.H., Shadlen, M.N., Newsome, W.T., & Movshon, J.A. (1992).

The analysis of visual motion: a comparison of neuronal and psychophysical performance. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 12(12), 4745-65. [PubMed:1464765] [WorldCat] - ↑

Salzman, C.D., Murasugi, C.M., Britten, K.H., & Newsome, W.T. (1992).

Microstimulation in visual area MT: effects on direction discrimination performance. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 12(6), 2331-55. [PubMed:1607944] [WorldCat] - ↑

Newsome, W.T., & Paré, E.B. (1988).

A selective impairment of motion perception following lesions of the middle temporal visual area (MT). The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 8(6), 2201-11. [PubMed:3385495] [WorldCat] - ↑

DeAngelis, G.C., Cumming, B.G., & Newsome, W.T. (1998).

Cortical area MT and the perception of stereoscopic depth. Nature, 394(6694), 677-80. [PubMed:9716130] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Freeman, J., & Simoncelli, E.P. (2011).

Metamers of the ventral stream. Nature neuroscience, 14(9), 1195-201. [PubMed:21841776] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Heeger, D.J., Simoncelli, E.P., & Movshon, J.A. (1996).

Computational models of cortical visual processing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(2), 623-7. [PubMed:8570605] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Rust, N.C., Mante, V., Simoncelli, E.P., & Movshon, J.A. (2006).

How MT cells analyze the motion of visual patterns. Nature neuroscience, 9(11), 1421-31. [PubMed:17041595] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 74.0 74.1

Pasupathy, A., & Connor, C.E. (2001).

Shape representation in area V4: position-specific tuning for boundary conformation. Journal of neurophysiology, 86(5), 2505-19. [PubMed:11698538] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Pasupathy, A., & Connor, C.E. (2002).

Population coding of shape in area V4. Nature neuroscience, 5(12), 1332-8. [PubMed:12426571] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Cadieu, C., Kouh, M., Pasupathy, A., Connor, C.E., Riesenhuber, M., & Poggio, T. (2007).

A model of V4 shape selectivity and invariance. Journal of neurophysiology, 98(3), 1733-50. [PubMed:17596412] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Brincat, S.L., & Connor, C.E. (2004).

Underlying principles of visual shape selectivity in posterior inferotemporal cortex. Nature neuroscience, 7(8), 880-6. [PubMed:15235606] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Yamane, Y., Carlson, E.T., Bowman, K.C., Wang, Z., & Connor, C.E. (2008).

A neural code for three-dimensional object shape in macaque inferotemporal cortex. Nature neuroscience, 11(11), 1352-60. [PubMed:18836443] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

David, S.V., Hayden, B.Y., & Gallant, J.L. (2006).

Spectral receptive field properties explain shape selectivity in area V4. Journal of neurophysiology, 96(6), 3492-505. [PubMed:16987926] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Naselaris, T., Prenger, R.J., Kay, K.N., Oliver, M., & Gallant, J.L. (2009).

Bayesian reconstruction of natural images from human brain activity. Neuron, 63(6), 902-15. [PubMed:19778517] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Roe, A.W., & Ts'o, D.Y. (1995).

Visual topography in primate V2: multiple representation across functional stripes. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 15(5 Pt 2), 3689-715. [PubMed:7751939] [WorldCat] - ↑

Shipp, S., & Zeki, S. (2002).

The functional organization of area V2, I: specialization across stripes and layers. Visual neuroscience, 19(2), 187-210. [PubMed:12385630] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Shipp, S., & Zeki, S. (2002).

The functional organization of area V2, II: the impact of stripes on visual topography. Visual neuroscience, 19(2), 211-31. [PubMed:12385631] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hegdé, J., & Van Essen, D.C. (2000).

Selectivity for complex shapes in primate visual area V2. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 20(5), RC61. [PubMed:10684908] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Ito, M., & Komatsu, H. (2004).

Representation of angles embedded within contour stimuli in area V2 of macaque monkeys. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 24(13), 3313-24. [PubMed:15056711] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Willmore, B.D., Prenger, R.J., & Gallant, J.L. (2010).

Neural representation of natural images in visual area V2. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 30(6), 2102-14. [PubMed:20147538] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 87.0 87.1

Zeki, S.M. (1969).

Representation of central visual fields in prestriate cortex of monkey. Brain research, 14(2), 271-91. [PubMed:4978525] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Lyon, D.C., & Kaas, J.H. (2002).

Evidence for a modified V3 with dorsal and ventral halves in macaque monkeys. Neuron, 33(3), 453-61. [PubMed:11832231] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Allman, J.M., & Kaas, J.H. (1975).

The dorsomedial cortical visual area: a third tier area in the occipital lobe of the owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus). Brain research, 100(3), 473-87. [PubMed:811327] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Gegenfurtner, K.R., Kiper, D.C., & Levitt, J.B. (1997).

Functional properties of neurons in macaque area V3. Journal of neurophysiology, 77(4), 1906-23. [PubMed:9114244] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Newsome, W.T., Maunsell, J.H., & Van Essen, D.C. (1986).

Ventral posterior visual area of the macaque: visual topography and areal boundaries. The Journal of comparative neurology, 252(2), 139-53. [PubMed:3782504] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Burkhalter, A., Felleman, D.J., Newsome, W.T., & Van Essen, D.C. (1986).

Anatomical and physiological asymmetries related to visual areas V3 and VP in macaque extrastriate cortex. Vision research, 26(1), 63-80. [PubMed:3716214] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

De Weerd, P., Gattass, R., Desimone, R., & Ungerleider, L.G. (1995).

Responses of cells in monkey visual cortex during perceptual filling-in of an artificial scotoma. Nature, 377(6551), 731-4. [PubMed:7477262] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Nakamura, K., & Colby, C.L. (2000).

Visual, saccade-related, and cognitive activation of single neurons in monkey extrastriate area V3A. Journal of neurophysiology, 84(2), 677-92. [PubMed:10938295] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Colby, C.L., Duhamel, J.R., & Goldberg, M.E. (1993).

Ventral intraparietal area of the macaque: anatomic location and visual response properties. Journal of neurophysiology, 69(3), 902-14. [PubMed:8385201] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

McKeefry, D.J., Burton, M.P., Vakrou, C., Barrett, B.T., & Morland, A.B. (2008).

Induced deficits in speed perception by transcranial magnetic stimulation of human cortical areas V5/MT+ and V3A. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 28(27), 6848-57. [PubMed:18596160] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Clifford, C.W., Freedman, J.N., & Vaina, L.M. (1998).

First- and second-order motion perception in Gabor micropattern stimuli: psychophysics and computational modelling. Brain research. Cognitive brain research, 6(4), 263-71. [PubMed:9593930] [WorldCat] - ↑

Press, W.A., Brewer, A.A., Dougherty, R.F., Wade, A.R., & Wandell, B.A. (2001).

Visual areas and spatial summation in human visual cortex. Vision research, 41(10-11), 1321-32. [PubMed:11322977] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hansen, K.A., Kay, K.N., & Gallant, J.L. (2007).

Topographic organization in and near human visual area V4. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 27(44), 11896-911. [PubMed:17978030] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 100.0 100.1

Wade, A.R., Brewer, A.A., Rieger, J.W., & Wandell, B.A. (2002).

Functional measurements of human ventral occipital cortex: retinotopy and colour. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 357(1424), 963-73. [PubMed:12217168] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Zeki, S.M. (1973).

Colour coding in rhesus monkey prestriate cortex. Brain research, 53(2), 422-7. [PubMed:4196224] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Essen, D.C., & Zeki, S.M. (1978).

The topographic organization of rhesus monkey prestriate cortex. The Journal of physiology, 277, 193-226. [PubMed:418173] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tanaka, M., Weber, H., & Creutzfeldt, O.D. (1986).

Visual properties and spatial distribution of neurones in the visual association area on the prelunate gyrus of the awake monkey. Experimental brain research, 65(1), 11-37. [PubMed:3803497] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tanigawa, H., Lu, H.D., & Roe, A.W. (2010).

Functional organization for color and orientation in macaque V4. Nature neuroscience, 13(12), 1542-8. [PubMed:21076422] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Conway, B.R., Moeller, S., & Tsao, D.Y. (2007).

Specialized color modules in macaque extrastriate cortex. Neuron, 56(3), 560-73. [PubMed:17988638] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Pasupathy, A., & Connor, C.E. (1999).

Responses to contour features in macaque area V4. Journal of neurophysiology, 82(5), 2490-502. [PubMed:10561421] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hinkle, D.A., & Connor, C.E. (2005).

Quantitative characterization of disparity tuning in ventral pathway area V4. Journal of neurophysiology, 94(4), 2726-37. [PubMed:15987762] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Desimone, R., & Schein, S.J. (1987).

Visual properties of neurons in area V4 of the macaque: sensitivity to stimulus form. Journal of neurophysiology, 57(3), 835-68. [PubMed:3559704] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Walsh, V., Carden, D., Butler, S.R., & Kulikowski, J.J. (1993).

The effects of V4 lesions on the visual abilities of macaques: hue discrimination and colour constancy. Behavioural brain research, 53(1-2), 51-62. [PubMed:8466667] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Schiller, P.H. (1993).

The effects of V4 and middle temporal (MT) area lesions on visual performance in the rhesus monkey. Visual neuroscience, 10(4), 717-46. [PubMed:8338809] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

De Weerd, P., Desimone, R., & Ungerleider, L.G. (1996).

Cue-dependent deficits in grating orientation discrimination after V4 lesions in macaques. Visual neuroscience, 13(3), 529-38. [PubMed:8782380] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

De Weerd, P., Peralta, M.R., Desimone, R., & Ungerleider, L.G. (1999).

Loss of attentional stimulus selection after extrastriate cortical lesions in macaques. Nature neuroscience, 2(8), 753-8. [PubMed:10412066] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Pearlman, A.L., Birch, J., & Meadows, J.C. (1979).

Cerebral color blindness: an acquired defect in hue discrimination. Annals of neurology, 5(3), 253-61. [PubMed:312619] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hadjikhani, N., Liu, A.K., Dale, A.M., Cavanagh, P., & Tootell, R.B. (1998).

Retinotopy and color sensitivity in human visual cortical area V8. Nature neuroscience, 1(3), 235-41. [PubMed:10195149] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tootell, R.B., & Hadjikhani, N. (2001).

Where is 'dorsal V4' in human visual cortex? Retinotopic, topographic and functional evidence. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 11(4), 298-311. [PubMed:11278193] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Allman, J.M., & Kaas, J.H. (1971).

A representation of the visual field in the caudal third of the middle tempral gyrus of the owl monkey (Aotus trivirgatus). Brain research, 31(1), 85-105. [PubMed:4998922] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 117.0 117.1

Dubner, R., & Zeki, S.M. (1971).

Response properties and receptive fields of cells in an anatomically defined region of the superior temporal sulcus in the monkey. Brain research, 35(2), 528-32. [PubMed:5002708] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tootell, R.B., & Taylor, J.B. (1995).

Anatomical evidence for MT and additional cortical visual areas in humans. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 5(1), 39-55. [PubMed:7719129] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Deyoe, E.A., Hockfield, S., Garren, H., & Van Essen, D.C. (1990).

Antibody labeling of functional subdivisions in visual cortex: Cat-301 immunoreactivity in striate and extrastriate cortex of the macaque monkey. Visual neuroscience, 5(1), 67-81. [PubMed:1702988] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tootell, R.B., Reppas, J.B., Kwong, K.K., Malach, R., Born, R.T., Brady, T.J., ..., & Belliveau, J.W. (1995).

Functional analysis of human MT and related visual cortical areas using magnetic resonance imaging. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 15(4), 3215-30. [PubMed:7722658] [WorldCat] - ↑

Watson, J.D., Myers, R., Frackowiak, R.S., Hajnal, J.V., Woods, R.P., Mazziotta, J.C., ..., & Zeki, S. (1993).

Area V5 of the human brain: evidence from a combined study using positron emission tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 3(2), 79-94. [PubMed:8490322] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ungerleider, L.G., & Desimone, R. (1986).

Cortical connections of visual area MT in the macaque. The Journal of comparative neurology, 248(2), 190-222. [PubMed:3722458] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Palmer, S.M., & Rosa, M.G. (2006).

A distinct anatomical network of cortical areas for analysis of motion in far peripheral vision. The European journal of neuroscience, 24(8), 2389-405. [PubMed:17042793] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Sincich, L.C., Park, K.F., Wohlgemuth, M.J., & Horton, J.C. (2004).

Bypassing V1: a direct geniculate input to area MT. Nature neuroscience, 7(10), 1123-8. [PubMed:15378066] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Maunsell, J.H., & Van Essen, D.C. (1983).

Functional properties of neurons in middle temporal visual area of the macaque monkey. I. Selectivity for stimulus direction, speed, and orientation. Journal of neurophysiology, 49(5), 1127-47. [PubMed:6864242] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Felleman, D.J., & Kaas, J.H. (1984).

Receptive-field properties of neurons in middle temporal visual area (MT) of owl monkeys. Journal of neurophysiology, 52(3), 488-513. [PubMed:6481441] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Albright, T.D., Desimone, R., & Gross, C.G. (1984).

Columnar organization of directionally selective cells in visual area MT of the macaque. Journal of neurophysiology, 51(1), 16-31. [PubMed:6693933] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

DeAngelis, G.C., & Newsome, W.T. (1999).

Organization of disparity-selective neurons in macaque area MT. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 19(4), 1398-415. [PubMed:9952417] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Zihl, J., von Cramon, D., & Mai, N. (1983).

Selective disturbance of movement vision after bilateral brain damage. Brain : a journal of neurology, 106 (Pt 2), 313-40. [PubMed:6850272] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hess, R.H., Baker, C.L., & Zihl, J. (1989).

The "motion-blind" patient: low-level spatial and temporal filters. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 9(5), 1628-40. [PubMed:2723744] [WorldCat] - ↑

Baker, C.L., Hess, R.F., & Zihl, J. (1991).

Residual motion perception in a "motion-blind" patient, assessed with limited-lifetime random dot stimuli. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 11(2), 454-61. [PubMed:1992012] [WorldCat] - ↑

Walsh, V., Ellison, A., Battelli, L., & Cowey, A. (1998).

Task-specific impairments and enhancements induced by magnetic stimulation of human visual area V5. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 265(1395), 537-43. [PubMed:9569672] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Galletti, C., Fattori, P., Battaglini, P.P., Shipp, S., & Zeki, S. (1996).

Functional demarcation of a border between areas V6 and V6A in the superior parietal gyrus of the macaque monkey. The European journal of neuroscience, 8(1), 30-52. [PubMed:8713448] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Galletti, C., Fattori, P., Gamberini, M., & Kutz, D.F. (1999).

The cortical visual area V6: brain location and visual topography. The European journal of neuroscience, 11(11), 3922-36. [PubMed:10583481] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Shipp, S., Blanton, M., & Zeki, S. (1998).

A visuo-somatomotor pathway through superior parietal cortex in the macaque monkey: cortical connections of areas V6 and V6A. The European journal of neuroscience, 10(10), 3171-93. [PubMed:9786211] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Rosa, M.G., Palmer, S.M., Gamberini, M., Tweedale, R., Piñon, M.C., & Bourne, J.A. (2005).

Resolving the organization of the New World monkey third visual complex: the dorsal extrastriate cortex of the marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). The Journal of comparative neurology, 483(2), 164-91. [PubMed:15678474] [WorldCat] [DOI]