「帯状皮質運動野」の版間の差分

細編集の要約なし |

細 →解剖 |

||

| (2人の利用者による、間の14版が非表示) | |||

| 1行目: | 1行目: | ||

英語名:cingulate motor area | |||

英略称:CMA | |||

帯状皮質運動野は、[[前頭葉]]内側部の[[帯状溝]](cingulate sulcus)に沿って存在する[[運動野]]である。[[一次運動野]]や[[脊髄]]に直接投射し、この領域を電気刺激すると運動が誘発され、広義の[[運動前野]]の1つとみなされる<ref name=ref1>'''Kandel, E.R., Schwartz, J.H. & Jessell, T.M.''' (eds.)<br>Principles of Neural Science, Edn. 4.<br>McGraw-Hill Medical, 2000</ref> <ref name=ref2>'''丹治順'''<br>脳と運動―アクションを実行させる脳<br>共立出版, 1999</ref>。また、帯状皮質運動野吻側部は、報酬の情報に基づく行動選択などの高次機能にも関与している。 | |||

== 解剖 == | |||

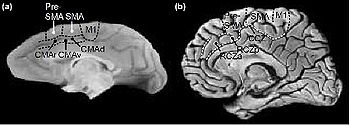

= | [[image:帯状皮質運動野1.jpg|thumb|350px|'''図1. 前頭葉内側部の解剖'''<br>サル (a)、ヒト (b) の前頭葉内側部を示す。CMAr: 帯状皮質運動野吻側部、CMAv: 帯状皮質運動野腹側部、CMAd: 帯状皮質運動野背側部、RCZa: 吻側帯状領域前方部、RCZp: 吻側帯状領域後方部、CCZ: 尾側帯状領域、pre-SMA: 前補足運動野、SMA: 補足運動野、M1: 一次運動野。(文献<ref name=ref73><pubmed>11741015</pubmed></ref>より引用)。CMAr は弓状溝(arcuate sulcus)膝部の前方、すなわち pre-SMA と前後方向にほぼ同レベルにあり、CMAc は弓状溝膝部の尾側、SMA と前後方向にほぼ同レベルにある。]] | ||

[[ | 帯状皮質運動野の解剖は、[[wikipedia:ja:サル|サル]](マカク)においてよく知られている。サルおよびヒトの帯状皮質運動野の位置を(図1)に示す。 | ||

サルを用いた研究によると、帯状皮質運動野は、細胞構築、および線維連絡の違いにより、3つの領域にわけられる。歴史的に、まず吻側部(rostral cingulate motor area; CMAr)、尾側部(caudal cingulate motor area; CMAc)の2領域にわけられ、さらに尾側部が背側部(dorsal cingulate motor area; CMAd)および腹側部(ventral cingulate motor area; CMAv)にわけられた<ref name=ref3><pubmed>2458281</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref4><pubmed>1705965</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref5><pubmed>8670662</pubmed></ref>。CMAr は主に[[ブロードマンの脳地図|ブロードマン]](Brodmann)の [[ブロードマン24野|24c野]]にあたり、帯状溝の上下に広がる。CMAd は帯状溝背側堤に存在する 6c、CMAv は帯状溝腹側堤の [[ブロードマン23野|23c野]] に相当する。サルでは、帯状溝の皮質運動野は帯状回の皮質野とはっきり区別される<ref name=ref6>'''Dum, R.P. & Strick, P.L.'''<br>Cingulate motor areas, in Neurobiology of cingulate cortex and limbic thalamus. <br>eds. B.A. Vogt & M. Gabriel, 415-441 (Birkhauser, Boston; 1993)</ref>。すなわち、帯状皮質運動野は、帯状溝に埋もれており、帯状回には達しない。帯状皮質運動野では、すべての亜領域で前肢を再現する部位が認められるのに対し、頭部、顔面や後肢を再現する部位は必ずしも明瞭ではない<ref name=ref7><pubmed>11860458</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

=== | サルとヒトでは脳の大きさおよび脳溝の走行が異なり、ヒトでは帯状溝の走行が個体間でかなり異なる<ref name=ref8>'''Ono, M., Kubik, S. & Abernathey, C.D.'''<br>Atlas of the cerebral sulci.<br>Thieme, New York; 1990.</ref> <ref name=ref9><pubmed>7499543</pubmed></ref>ため、ヒトにおいて上述の部位と正確に相同な領域は同定できないが、吻側帯状領域(rostral cingulate zone; RCZ)および尾側帯状領域(caudal cingulate zone; CCZ)が帯状皮質運動野に相当する。CCZ は VCA line(vertical commissure anterior line; [[前交連]]を通り、前交連後交連結合線 AC-PC line に垂直な線)付近の [[ブロードマン24野|24野]]にあり、比較的単純な運動課題の遂行にて活動する<ref name=ref5 />。その位置、細胞構築<ref name=ref4 />、および活動パターンから、サルの CMAd に対応すると考えられる<ref name=ref5 />。RCZ は、主に [[ブロードマン32野|32野]]、一部 24c 野にあり、前方の RCZa(anterior portion of the RCZ)と、後方の RCZp(posterior portion of the RCZ)の2領域にわけられる。その活動パターンと位置から、RCZa はサルの CMAr に対応し、残る RCZp は CMAv に対応すると推測されているが、これは CCZ と CMAd の対応と比較し、憶測的である。ヒトの RCZp とサルの CMAv には、解剖学的な乖離がある。サルの CMAv は CMAd の腹側にあるが、ヒトの RCZp は特に上肢領域で CCZ より背側にある。また、サルの CMAv は 23c野にある<ref name=ref4 />が、ヒトの RCZp は主に 32野にある。(ただし、サルの 23 野がヒトの 23 野に相当するとは考えにくい。ヒトの 23野は motor task では活動がみられず、体性感覚刺激にて反応し<ref name=ref10><pubmed>12106480</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref11><pubmed>1519476</pubmed></ref>、電気刺激により、運動ではなく[[体性感覚]]が誘発される<ref name=ref12><pubmed>8467887</pubmed></ref>。) | ||

なお、いわゆる[[前帯状皮質]](anterior cingulate cortex; ACC)とは、帯状回のブロードマン 24a、24b、[[ブロードマン25野|25野]]と、帯状溝内の 24c 野および 32 野を含む広い領域を指す<ref name=ref13><pubmed>11389475</pubmed></ref>。したがって、CMAr は、前帯状皮質に含まれる。前帯状皮質を、背側前帯状皮質(dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; dACC)、吻側前帯状皮質(rostral anterior cingulate cortex; rACC)、の2領域にわけることもあるが、ヒトの dACC は、脳梁膝部(genu of the corpus callosum)から VCA line までの、帯状溝の背側部と腹側部を含む領域(24b-c・32 野)で、認知機能に関与し(cognitive division)、サルの CMAr にほぼ相当する。rACC は、[[脳梁]]膝部より吻側、腹側(24a-c・32 野、25・[[ブロードマン23野|33野]])にあり、情動処理に関係する(affective division)<ref name=ref14><pubmed>10827444</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref15><pubmed>16227444</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

=== 線維連絡 === | |||

帯状皮質運動野は、次の部位から入力を受ける:[[側頭連合野]]前部<ref name=ref16><pubmed>3624555</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref17><pubmed>9443842</pubmed></ref>、[[頭頂連合野]]下部<ref name=ref16><pubmed>3624555</pubmed></ref>、[[前頭前野]]外側面<ref name=ref18><pubmed>8288777</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref19><pubmed>7515081</pubmed></ref>(ただし、[[46 野]]]からの直接入力はわずかで、主に運動前野(PMdr と PMvr)を介して CMAr へ入力する<ref name=ref20><pubmed>15217388</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref21><pubmed>12761828</pubmed></ref>)、[[前補足運動野]](pre-supplementary motor area; pre-SMA)<ref name=ref21><pubmed>12761828</pubmed></ref>、[[帯状回]]<ref name=ref17><pubmed>9443842</pubmed></ref>、[[眼窩前頭皮質]](orbitofrontal cortex)<ref name=ref16><pubmed>3624555</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref17><pubmed>9443842</pubmed></ref>、[[扁桃核]]と[[海馬傍回]]<ref name=ref16><pubmed>3624555</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref17><pubmed>9443842</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref22><pubmed>15335441</pubmed></ref>、[[後頭葉]]([[鳥距溝後部]])<ref name=ref17><pubmed>9443842</pubmed></ref>、[[島皮質]]<ref name=ref16><pubmed>3624555</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref17><pubmed>9443842</pubmed></ref>、[[視床]]([[外側腹側核]]の口領域(VLo)、[[視床髄板内核群]](IL)、さらに、CMAr は[[視床前核]]、CMAc は[[後外側腹側核]](VPL)の口領域および外側腹側核(VL)の尾側部からの入力も受ける)<ref name=ref21 /> <ref name=ref23><pubmed>3624554</pubmed></ref>。また、[[中脳]]から[[ドーパミン]]性の入力も受ける<ref name=ref24><pubmed>2563268</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref25><pubmed>8100725</pubmed></ref>。すなわち、側頭・頭頂連合野から外界環境に関する情報を、[[辺縁系]]から[[情動]]・[[内的欲求]]や身体の状態などに関する情報を、前頭前野から行動全体の遂行状況に関する情報を受け取る。 | |||

帯状皮質運動野からの出力に関しては、[[一次運動野]]、[[脳幹]]([[赤核]]、[[橋]])、[[脊髄]]<ref name=ref3 /> <ref name=ref5 /> <ref name=ref26><pubmed>115545</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref27><pubmed>11164252</pubmed></ref>、[[補足運動野]]<ref name=ref27 />, <ref name=ref28><pubmed>1383283</pubmed></ref>、前補足運動野<ref name=ref27 /> <ref name=ref29><pubmed>7507940</pubmed></ref>、運動前野<ref name=ref30><pubmed>1721118</pubmed></ref>、[[大脳基底核]]([[線条体]]吻側部および[[視床下核]])<ref name=ref7 />へ投射する。 | |||

=== | 前補足運動野と帯状皮質運動野は相互に密接な連絡を持ち、運動の高次のコントロールに強く関与していると考えられる。また、帯状回<ref name=ref16 />、扁桃体<ref name=ref31><pubmed>17099887</pubmed></ref>とも相互に連絡し、帯状皮質運動野内の各亜領域も互いに強く連絡している<ref name=ref17 />。このように、帯状皮質運動野は、内的および外的の情報を受けて、運動出力を行う領野へ情報を送るため、様々な情報に基づいた自発的な行動選択に大きな役割を果たしていると考えられている<ref name=ref17 />。 | ||

帯状皮質運動野の各亜領域では、それぞれ線維連絡のようすが異なり、[[一次運動野]]や頭頂葉、視床などの各対象領野との連絡部位も各亜領域間で異なる。入出力のパターンも異なり、例えば、帯状皮質運動野の尾側部は、一次運動野、補足運動野、前補足運動野から投射を受けるが、吻側部は一次運動野、補足運動野からの投射を受けない<ref name=ref21 />。また、帯状皮質運動野吻側部は、前補足運動野へ豊富に投射するが、一次運動野への投射は多くない。一方、尾側部は一次運動野への投射が多く、前補足運動野への投射は少ない<ref name=ref27 /> <ref name=ref29 />。なお、補足運動野への投射に関しては、吻側部・尾側部から同程度ある<ref name=ref27 />という報告と、尾側部から多く、吻側部からは少ない、という報告<ref name=ref29 />がある。吻側部、尾側部ともに扁桃体からの入力を受けるが、特に吻側部の顔領域への入力が豊富である。扁桃体 → 帯状皮質運動野吻側部 → [[顔面神経核]](橋)の経路が、感情的な表情の表出に関与していると考えられている<ref name=ref31 />。 | |||

== 電気生理学的事項 == | |||

帯状皮質運動野の正確な位置や解剖学的構造が解明される以前の 20世紀半ばに、この領域を電気刺激すると運動が誘発されることが、サルおよびヒトで報告された<ref name=ref13 /> <ref name=ref32><pubmed>14446213</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref33><pubmed>14867993</pubmed></ref>。その後、皮質内微小電気刺激を用いることにより、帯状皮質運動野の各亜領域の特性を観察することが可能になった。帯状皮質運動野尾側部は、比較的低強度(40 μA 以下)の電気刺激にて運動を誘発することが可能で、[[体性局在]]も確認された。一方、吻側部は、刺激強度を増しても常に運動が誘発されるわけではなく、体性局在も不明瞭であった<ref name=ref34><pubmed>1757598</pubmed></ref>。その理由の1つとして、脊髄へ直接投射する細胞の密度が、吻側部よりも尾側部のほうが高いことが考えられている<ref name=ref4 /> <ref name=ref5 />。 | |||

また、動作遂行に際して、この領域の細胞が活動することが知られている。開始信号によって開始する動作と、自発的に開始する動作を遂行する際の細胞活動を調べた研究では<ref name=ref35><pubmed>2016637</pubmed></ref>、帯状皮質運動野の約 40% の細胞は、両条件において同様な活動を呈した。自発的な運動開始の際に選択的に活動する細胞は、前方領域に多くみられた。さらに、動作の開始時点よりかなり早くからの(500 ms - 2 s 前)細胞活動もみられたが、この活動は、主に自発的な運動開始の際にみられ、このような活動を呈する細胞は、前方領域に多かった。したがって、後方領域は運動の実行に直接的に関与し、前方領域はより高次の運動コントロールに関与していることが考えられる<ref name=ref35 />(文献<ref name=ref36><pubmed>12954861</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref37><pubmed>12424298</pubmed></ref>も参照のこと)。また、前方領域、特に CMAr には、運動の実行のみならず、運動の不実行に関与する細胞も多く存在する<ref name=ref36 />。 | |||

== | == 高次機能 == | ||

帯状皮質運動野(主に CMAr)は、最適な行動選択を行うために必要な情報処理に関与する。サルの単一神経細胞記録や[[破壊実験]]によると、この領域は以下のような機能に関わるといわれている。[[報酬]]の情報に基づいた[[運動選択]](reward-based motor selection)<ref name=ref38><pubmed>9812901</pubmed></ref>、[[エラー]]の検出(error detection)<ref name=ref39><pubmed>111772</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref40><pubmed>14526085</pubmed></ref>、行動のイベント経過のモニター<ref name=ref41><pubmed>15703223</pubmed></ref>、正しい[[行動順序]]の探索<ref name=ref42><pubmed>10769392</pubmed></ref>、[[行動の価値]](action value)の推定<ref name=ref43><pubmed>16783368 </pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref44><pubmed>18215627</pubmed></ref>、報酬の予測と[[予測誤差]](prediction error)の検出<ref name=ref45><pubmed>12040201</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref46><pubmed>16207931</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref47><pubmed>17670983</pubmed></ref>、自分自身はとらなかった行動に導かれる「経験していない結果(fictive outcome)」の情報処理<ref name=ref48><pubmed>19443783</pubmed></ref>等である。帯状皮質運動野が、これらのうち、もしくは別の1つの機能に特化していると説明しようとするより、行動(action)・結果(outcome)のモニタリングおよび評価を次の行動につなげる意思決定(decision making)過程に関与すると考えるほうが自然であろう。なお、帯状皮質運動野より前方部分の前帯状皮質においても、予測誤差の検出<ref name=ref49><pubmed>17450137</pubmed></ref>、報酬の有無や報酬量、報酬獲得に必要な労力に関連した活動<ref name=ref50><pubmed>19453638</pubmed></ref>等の報告があり、この領域一帯の細胞は、報酬の情報に基づいた行動選択に関わると考えられる。また、1つの細胞が複数の異なる情報をコードしたり、異なる情報(例えば、報酬が得られる確率と予測誤差など)をコードする細胞が領域内で混在したりしていることもしばしば報告される<ref name=ref47 /> <ref name=ref50 />。 | |||

同様に、ヒトを対象とした [[fMRI]]、[[PET]] の研究においても、エラーの検出など行動の評価(action valuation)に関わる情報処理や、自己の意思による行動選択の際に帯状皮質運動野の活動がみられる<ref name=ref5 /> <ref name=ref51><pubmed>1679944</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref52><pubmed>11707094</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref53><pubmed>15097995</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref54><pubmed>15494729</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

=== | また、[[ストループ課題]](Stroop task)など、2つの情報が干渉し合うような課題を遂行中のヒト脳機能画像研究の結果から、前帯状皮質が反応の競合(response conflict)の検出を行っているという仮説が提唱された<ref name=ref55><pubmed>11488380 </pubmed></ref>。この仮説は、前帯状皮質のエラー検出機能についても一元的に説明できる仮説(conflict monitoring hypothesis)として支配的となった<ref name=ref56><pubmed>9563953</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref57><pubmed>15556023</pubmed></ref>が、その一方で、サルを対象とした単一神経細胞活動記録実験からは、前帯状皮質の conflict monitoring hypothesis を支持する結果は得られていない<ref name=ref40 />, <ref name=ref58><pubmed>15295008</pubmed></ref>。 | ||

帯状皮質運動野は体部位局在を持つが、高次コントロール機能においても、出力様式([[眼球運動]]、[[wikipedia:ja:上肢|上肢]]の運動など)による局在がある<ref name=ref5 /> <ref name=ref59><pubmed>8410148</pubmed></ref>。帯状皮質運動野の[[脳腫]]瘍切除後の患者に、2つの出力様式(手指によるボタン押し、声)で、2種類の課題(2回の刺激に差異があるかを検出する課題と、ストループ課題)を行ったところ、両課題とも手指により反応する際はコントロール群と比較し成績が悪かったが、口答する場合にはコントロール群と同等の成績であったという報告がある<ref name=ref60><pubmed>10491614</pubmed></ref>。サルにおいても、CMAr の前肢領域を[[ムシモール]]によりブロックすると、課題(報酬減少を察知して前肢による運動を別の運動に切り替える課題)の遂行が不可能になるが、後肢領域をブロックしても課題遂行に影響が表れなかったと報告されている<ref name=ref38 />。 | |||

最近の研究結果によると、CMAr およびその前方領域の細胞は、自分自身が運動する際だけでなく、他個体の運動を観察する際や、その両方で活動する<ref name=ref61><pubmed>21256015</pubmed></ref>。また,他個体の行動エラーの検出にも関わる<ref name=ref62><pubmed>22864610</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

== 臨床学的事項 == | |||

一次運動野の顔面領域に障害がある患者も、感情的な表情を表出することができる。これには、辺縁系から帯状皮質運動野を介し、顔面神経核に至る経路が関与していることが推測されている<ref name=ref31 />。 | |||

[[帯状回てんかん]](cingulate cortex seizure)では[[口部自動症]]や複雑な[[身振り自動症]]がみられる。これは、帯状皮質運動野の機能を考える一助となる<ref name=ref63><pubmed>7895011</pubmed></ref>。[[内側側頭葉てんかん]](mesial temporal lobe epilepsy; MTLE)では、運動停止、口部自動症、顔面・頚部・上肢を含む複雑な自動症がみられるが、この原因の1つとして、焦点である扁桃体、側頭葉腹内側部から、CMAr の主に顔面・上肢領域が直接入力を受けることが挙げられる<ref name=ref31 />。 | |||

== | 古くから、帯状皮質運動野を含む障害により、[[無言無動症]](akinetic mutism; [[追視]]があり、[[麻痺]]はなく、反射は正常であるが、自発的な運動が消失し、どのような形でも意思疎通がはかれない状態)をきたすことが報告されている<ref name=ref64><pubmed>14839354</pubmed></ref>。しかし、帯状皮質に限局した障害により、数日以上の無動もしくは無言症をきたしたという報告はなく、この一過性の症状も、周辺領域の一過性の血流障害による可能性が指摘されている<ref name=ref63 />。無言無動症は、前帯状皮質(脳梁膝部付近)と補足運動野を含む領域の両側性障害により引き起こされるという考察がなされている<ref name=ref63 /> <ref name=ref65><pubmed>2849547</pubmed></ref>。 | ||

難治性の[[うつ病]](depression)、[[強迫神経症]](obsessive compulsive disorder; OCD)に外科的治療を行うことがある。術式の1つに前帯状回破壊術(anterior cingulotomy)があり、両側ブロードマン 24/32 野に小破壊巣を作るが、これは、帯状皮質運動野ではなく、[[帯状束]](cingulum bundle)をターゲットとしている<ref name=ref66><pubmed> 19759530</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref67><pubmed>20736994</pubmed></ref>。これらの精神疾患、特に強迫神経症では、[[皮質-基底核-視床ループ]]の1つである[[辺縁系ループ]](limbic loop)が病態に深く関わっていると考えられ、強迫神経症患者における辺縁系ループの各構成要素の活動は、コントロール群と比較し上昇しており、症状を誘発した際にはさらに上昇し、治療により低下してゆく<ref name=ref66 /> <ref name=ref68><pubmed>22138231</pubmed></ref>。手術では、辺縁系ループの連絡を各所で阻害する(上記 anterior cingulotomy や、anterior capsulotomy、subcaudate tractotomy、limbic leukotomy、および[[内包]]前脚腹側部/線条体腹側部(VC/VS)、[[尾状核]]腹側部、視床下核の[[脳深部刺激]](deep brain stimulation; DBS))<ref name=ref66 />。なお、前帯状皮質 は、眼窩前頭皮質などとともに辺縁系ループを構成する。帯状皮質運動野は、これとは別の、[[運動ループ]](motor loop)を構成するのであるが、最近の研究では、辺縁系ループだけでなく、dACC のエラー処理および conflict monitoring の異常や、扁桃体も強迫神経症の病態に関与していると考えられている<ref name=ref68 />。その他、dACC は、[[心的外傷後ストレス障害]](posttraumatic stress disorder; PTSD)、[[不安障害]](anxiety disorders)、[[薬物乱用]]と関わっているといわれている<ref name=ref69><pubmed>17928261</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref70><pubmed>19625997</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref71><pubmed>19716751</pubmed></ref> <ref name=ref72><pubmed>15808502</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

== 参考文献 == | |||

<references /> | |||

(執筆者:吉田今日子、磯田昌岐 担当編集委員:伊佐正) | |||

2012年9月8日 (土) 15:09時点における版

英語名:cingulate motor area

英略称:CMA

帯状皮質運動野は、前頭葉内側部の帯状溝(cingulate sulcus)に沿って存在する運動野である。一次運動野や脊髄に直接投射し、この領域を電気刺激すると運動が誘発され、広義の運動前野の1つとみなされる[1] [2]。また、帯状皮質運動野吻側部は、報酬の情報に基づく行動選択などの高次機能にも関与している。

解剖

サル (a)、ヒト (b) の前頭葉内側部を示す。CMAr: 帯状皮質運動野吻側部、CMAv: 帯状皮質運動野腹側部、CMAd: 帯状皮質運動野背側部、RCZa: 吻側帯状領域前方部、RCZp: 吻側帯状領域後方部、CCZ: 尾側帯状領域、pre-SMA: 前補足運動野、SMA: 補足運動野、M1: 一次運動野。(文献[3]より引用)。CMAr は弓状溝(arcuate sulcus)膝部の前方、すなわち pre-SMA と前後方向にほぼ同レベルにあり、CMAc は弓状溝膝部の尾側、SMA と前後方向にほぼ同レベルにある。

帯状皮質運動野の解剖は、サル(マカク)においてよく知られている。サルおよびヒトの帯状皮質運動野の位置を(図1)に示す。

サルを用いた研究によると、帯状皮質運動野は、細胞構築、および線維連絡の違いにより、3つの領域にわけられる。歴史的に、まず吻側部(rostral cingulate motor area; CMAr)、尾側部(caudal cingulate motor area; CMAc)の2領域にわけられ、さらに尾側部が背側部(dorsal cingulate motor area; CMAd)および腹側部(ventral cingulate motor area; CMAv)にわけられた[4] [5] [6]。CMAr は主にブロードマン(Brodmann)の 24c野にあたり、帯状溝の上下に広がる。CMAd は帯状溝背側堤に存在する 6c、CMAv は帯状溝腹側堤の 23c野 に相当する。サルでは、帯状溝の皮質運動野は帯状回の皮質野とはっきり区別される[7]。すなわち、帯状皮質運動野は、帯状溝に埋もれており、帯状回には達しない。帯状皮質運動野では、すべての亜領域で前肢を再現する部位が認められるのに対し、頭部、顔面や後肢を再現する部位は必ずしも明瞭ではない[8]。

サルとヒトでは脳の大きさおよび脳溝の走行が異なり、ヒトでは帯状溝の走行が個体間でかなり異なる[9] [10]ため、ヒトにおいて上述の部位と正確に相同な領域は同定できないが、吻側帯状領域(rostral cingulate zone; RCZ)および尾側帯状領域(caudal cingulate zone; CCZ)が帯状皮質運動野に相当する。CCZ は VCA line(vertical commissure anterior line; 前交連を通り、前交連後交連結合線 AC-PC line に垂直な線)付近の 24野にあり、比較的単純な運動課題の遂行にて活動する[6]。その位置、細胞構築[5]、および活動パターンから、サルの CMAd に対応すると考えられる[6]。RCZ は、主に 32野、一部 24c 野にあり、前方の RCZa(anterior portion of the RCZ)と、後方の RCZp(posterior portion of the RCZ)の2領域にわけられる。その活動パターンと位置から、RCZa はサルの CMAr に対応し、残る RCZp は CMAv に対応すると推測されているが、これは CCZ と CMAd の対応と比較し、憶測的である。ヒトの RCZp とサルの CMAv には、解剖学的な乖離がある。サルの CMAv は CMAd の腹側にあるが、ヒトの RCZp は特に上肢領域で CCZ より背側にある。また、サルの CMAv は 23c野にある[5]が、ヒトの RCZp は主に 32野にある。(ただし、サルの 23 野がヒトの 23 野に相当するとは考えにくい。ヒトの 23野は motor task では活動がみられず、体性感覚刺激にて反応し[11] [12]、電気刺激により、運動ではなく体性感覚が誘発される[13]。)

なお、いわゆる前帯状皮質(anterior cingulate cortex; ACC)とは、帯状回のブロードマン 24a、24b、25野と、帯状溝内の 24c 野および 32 野を含む広い領域を指す[14]。したがって、CMAr は、前帯状皮質に含まれる。前帯状皮質を、背側前帯状皮質(dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; dACC)、吻側前帯状皮質(rostral anterior cingulate cortex; rACC)、の2領域にわけることもあるが、ヒトの dACC は、脳梁膝部(genu of the corpus callosum)から VCA line までの、帯状溝の背側部と腹側部を含む領域(24b-c・32 野)で、認知機能に関与し(cognitive division)、サルの CMAr にほぼ相当する。rACC は、脳梁膝部より吻側、腹側(24a-c・32 野、25・33野)にあり、情動処理に関係する(affective division)[15] [16]。

線維連絡

帯状皮質運動野は、次の部位から入力を受ける:側頭連合野前部[17] [18]、頭頂連合野下部[17]、前頭前野外側面[19] [20](ただし、46 野]からの直接入力はわずかで、主に運動前野(PMdr と PMvr)を介して CMAr へ入力する[21] [22])、前補足運動野(pre-supplementary motor area; pre-SMA)[22]、帯状回[18]、眼窩前頭皮質(orbitofrontal cortex)[17] [18]、扁桃核と海馬傍回[17] [18] [23]、後頭葉(鳥距溝後部)[18]、島皮質[17] [18]、視床(外側腹側核の口領域(VLo)、視床髄板内核群(IL)、さらに、CMAr は視床前核、CMAc は後外側腹側核(VPL)の口領域および外側腹側核(VL)の尾側部からの入力も受ける)[22] [24]。また、中脳からドーパミン性の入力も受ける[25] [26]。すなわち、側頭・頭頂連合野から外界環境に関する情報を、辺縁系から情動・内的欲求や身体の状態などに関する情報を、前頭前野から行動全体の遂行状況に関する情報を受け取る。

帯状皮質運動野からの出力に関しては、一次運動野、脳幹(赤核、橋)、脊髄[4] [6] [27] [28]、補足運動野[28], [29]、前補足運動野[28] [30]、運動前野[31]、大脳基底核(線条体吻側部および視床下核)[8]へ投射する。

前補足運動野と帯状皮質運動野は相互に密接な連絡を持ち、運動の高次のコントロールに強く関与していると考えられる。また、帯状回[17]、扁桃体[32]とも相互に連絡し、帯状皮質運動野内の各亜領域も互いに強く連絡している[18]。このように、帯状皮質運動野は、内的および外的の情報を受けて、運動出力を行う領野へ情報を送るため、様々な情報に基づいた自発的な行動選択に大きな役割を果たしていると考えられている[18]。

帯状皮質運動野の各亜領域では、それぞれ線維連絡のようすが異なり、一次運動野や頭頂葉、視床などの各対象領野との連絡部位も各亜領域間で異なる。入出力のパターンも異なり、例えば、帯状皮質運動野の尾側部は、一次運動野、補足運動野、前補足運動野から投射を受けるが、吻側部は一次運動野、補足運動野からの投射を受けない[22]。また、帯状皮質運動野吻側部は、前補足運動野へ豊富に投射するが、一次運動野への投射は多くない。一方、尾側部は一次運動野への投射が多く、前補足運動野への投射は少ない[28] [30]。なお、補足運動野への投射に関しては、吻側部・尾側部から同程度ある[28]という報告と、尾側部から多く、吻側部からは少ない、という報告[30]がある。吻側部、尾側部ともに扁桃体からの入力を受けるが、特に吻側部の顔領域への入力が豊富である。扁桃体 → 帯状皮質運動野吻側部 → 顔面神経核(橋)の経路が、感情的な表情の表出に関与していると考えられている[32]。

電気生理学的事項

帯状皮質運動野の正確な位置や解剖学的構造が解明される以前の 20世紀半ばに、この領域を電気刺激すると運動が誘発されることが、サルおよびヒトで報告された[14] [33] [34]。その後、皮質内微小電気刺激を用いることにより、帯状皮質運動野の各亜領域の特性を観察することが可能になった。帯状皮質運動野尾側部は、比較的低強度(40 μA 以下)の電気刺激にて運動を誘発することが可能で、体性局在も確認された。一方、吻側部は、刺激強度を増しても常に運動が誘発されるわけではなく、体性局在も不明瞭であった[35]。その理由の1つとして、脊髄へ直接投射する細胞の密度が、吻側部よりも尾側部のほうが高いことが考えられている[5] [6]。

また、動作遂行に際して、この領域の細胞が活動することが知られている。開始信号によって開始する動作と、自発的に開始する動作を遂行する際の細胞活動を調べた研究では[36]、帯状皮質運動野の約 40% の細胞は、両条件において同様な活動を呈した。自発的な運動開始の際に選択的に活動する細胞は、前方領域に多くみられた。さらに、動作の開始時点よりかなり早くからの(500 ms - 2 s 前)細胞活動もみられたが、この活動は、主に自発的な運動開始の際にみられ、このような活動を呈する細胞は、前方領域に多かった。したがって、後方領域は運動の実行に直接的に関与し、前方領域はより高次の運動コントロールに関与していることが考えられる[36](文献[37] [38]も参照のこと)。また、前方領域、特に CMAr には、運動の実行のみならず、運動の不実行に関与する細胞も多く存在する[37]。

高次機能

帯状皮質運動野(主に CMAr)は、最適な行動選択を行うために必要な情報処理に関与する。サルの単一神経細胞記録や破壊実験によると、この領域は以下のような機能に関わるといわれている。報酬の情報に基づいた運動選択(reward-based motor selection)[39]、エラーの検出(error detection)[40] [41]、行動のイベント経過のモニター[42]、正しい行動順序の探索[43]、行動の価値(action value)の推定[44] [45]、報酬の予測と予測誤差(prediction error)の検出[46] [47] [48]、自分自身はとらなかった行動に導かれる「経験していない結果(fictive outcome)」の情報処理[49]等である。帯状皮質運動野が、これらのうち、もしくは別の1つの機能に特化していると説明しようとするより、行動(action)・結果(outcome)のモニタリングおよび評価を次の行動につなげる意思決定(decision making)過程に関与すると考えるほうが自然であろう。なお、帯状皮質運動野より前方部分の前帯状皮質においても、予測誤差の検出[50]、報酬の有無や報酬量、報酬獲得に必要な労力に関連した活動[51]等の報告があり、この領域一帯の細胞は、報酬の情報に基づいた行動選択に関わると考えられる。また、1つの細胞が複数の異なる情報をコードしたり、異なる情報(例えば、報酬が得られる確率と予測誤差など)をコードする細胞が領域内で混在したりしていることもしばしば報告される[48] [51]。

同様に、ヒトを対象とした fMRI、PET の研究においても、エラーの検出など行動の評価(action valuation)に関わる情報処理や、自己の意思による行動選択の際に帯状皮質運動野の活動がみられる[6] [52] [53] [54] [55]。

また、ストループ課題(Stroop task)など、2つの情報が干渉し合うような課題を遂行中のヒト脳機能画像研究の結果から、前帯状皮質が反応の競合(response conflict)の検出を行っているという仮説が提唱された[56]。この仮説は、前帯状皮質のエラー検出機能についても一元的に説明できる仮説(conflict monitoring hypothesis)として支配的となった[57] [58]が、その一方で、サルを対象とした単一神経細胞活動記録実験からは、前帯状皮質の conflict monitoring hypothesis を支持する結果は得られていない[41], [59]。

帯状皮質運動野は体部位局在を持つが、高次コントロール機能においても、出力様式(眼球運動、上肢の運動など)による局在がある[6] [60]。帯状皮質運動野の脳腫瘍切除後の患者に、2つの出力様式(手指によるボタン押し、声)で、2種類の課題(2回の刺激に差異があるかを検出する課題と、ストループ課題)を行ったところ、両課題とも手指により反応する際はコントロール群と比較し成績が悪かったが、口答する場合にはコントロール群と同等の成績であったという報告がある[61]。サルにおいても、CMAr の前肢領域をムシモールによりブロックすると、課題(報酬減少を察知して前肢による運動を別の運動に切り替える課題)の遂行が不可能になるが、後肢領域をブロックしても課題遂行に影響が表れなかったと報告されている[39]。

最近の研究結果によると、CMAr およびその前方領域の細胞は、自分自身が運動する際だけでなく、他個体の運動を観察する際や、その両方で活動する[62]。また,他個体の行動エラーの検出にも関わる[63]。

臨床学的事項

一次運動野の顔面領域に障害がある患者も、感情的な表情を表出することができる。これには、辺縁系から帯状皮質運動野を介し、顔面神経核に至る経路が関与していることが推測されている[32]。

帯状回てんかん(cingulate cortex seizure)では口部自動症や複雑な身振り自動症がみられる。これは、帯状皮質運動野の機能を考える一助となる[64]。内側側頭葉てんかん(mesial temporal lobe epilepsy; MTLE)では、運動停止、口部自動症、顔面・頚部・上肢を含む複雑な自動症がみられるが、この原因の1つとして、焦点である扁桃体、側頭葉腹内側部から、CMAr の主に顔面・上肢領域が直接入力を受けることが挙げられる[32]。

古くから、帯状皮質運動野を含む障害により、無言無動症(akinetic mutism; 追視があり、麻痺はなく、反射は正常であるが、自発的な運動が消失し、どのような形でも意思疎通がはかれない状態)をきたすことが報告されている[65]。しかし、帯状皮質に限局した障害により、数日以上の無動もしくは無言症をきたしたという報告はなく、この一過性の症状も、周辺領域の一過性の血流障害による可能性が指摘されている[64]。無言無動症は、前帯状皮質(脳梁膝部付近)と補足運動野を含む領域の両側性障害により引き起こされるという考察がなされている[64] [66]。

難治性のうつ病(depression)、強迫神経症(obsessive compulsive disorder; OCD)に外科的治療を行うことがある。術式の1つに前帯状回破壊術(anterior cingulotomy)があり、両側ブロードマン 24/32 野に小破壊巣を作るが、これは、帯状皮質運動野ではなく、帯状束(cingulum bundle)をターゲットとしている[67] [68]。これらの精神疾患、特に強迫神経症では、皮質-基底核-視床ループの1つである辺縁系ループ(limbic loop)が病態に深く関わっていると考えられ、強迫神経症患者における辺縁系ループの各構成要素の活動は、コントロール群と比較し上昇しており、症状を誘発した際にはさらに上昇し、治療により低下してゆく[67] [69]。手術では、辺縁系ループの連絡を各所で阻害する(上記 anterior cingulotomy や、anterior capsulotomy、subcaudate tractotomy、limbic leukotomy、および内包前脚腹側部/線条体腹側部(VC/VS)、尾状核腹側部、視床下核の脳深部刺激(deep brain stimulation; DBS))[67]。なお、前帯状皮質 は、眼窩前頭皮質などとともに辺縁系ループを構成する。帯状皮質運動野は、これとは別の、運動ループ(motor loop)を構成するのであるが、最近の研究では、辺縁系ループだけでなく、dACC のエラー処理および conflict monitoring の異常や、扁桃体も強迫神経症の病態に関与していると考えられている[69]。その他、dACC は、心的外傷後ストレス障害(posttraumatic stress disorder; PTSD)、不安障害(anxiety disorders)、薬物乱用と関わっているといわれている[70] [71] [72] [73]。

参考文献

- ↑ Kandel, E.R., Schwartz, J.H. & Jessell, T.M. (eds.)

Principles of Neural Science, Edn. 4.

McGraw-Hill Medical, 2000 - ↑ 丹治順

脳と運動―アクションを実行させる脳

共立出版, 1999 - ↑

Picard, N., & Strick, P.L. (2001).

Imaging the premotor areas. Current opinion in neurobiology, 11(6), 663-72. [PubMed:11741015] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 4.0 4.1

Hutchins, K.D., Martino, A.M., & Strick, P.L. (1988).

Corticospinal projections from the medial wall of the hemisphere. Experimental brain research, 71(3), 667-72. [PubMed:2458281] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3

Dum, R.P., & Strick, P.L. (1991).

The origin of corticospinal projections from the premotor areas in the frontal lobe. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 11(3), 667-89. [PubMed:1705965] [WorldCat] - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6

Picard, N., & Strick, P.L. (1996).

Motor areas of the medial wall: a review of their location and functional activation. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 6(3), 342-53. [PubMed:8670662] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ Dum, R.P. & Strick, P.L.

Cingulate motor areas, in Neurobiology of cingulate cortex and limbic thalamus.

eds. B.A. Vogt & M. Gabriel, 415-441 (Birkhauser, Boston; 1993) - ↑ 8.0 8.1

Takada, M., Tokuno, H., Hamada, I., Inase, M., Ito, Y., Imanishi, M., ..., & Nambu, A. (2001).

Organization of inputs from cingulate motor areas to basal ganglia in macaque monkey. The European journal of neuroscience, 14(10), 1633-50. [PubMed:11860458] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ Ono, M., Kubik, S. & Abernathey, C.D.

Atlas of the cerebral sulci.

Thieme, New York; 1990. - ↑

Vogt, B.A., Nimchinsky, E.A., Vogt, L.J., & Hof, P.R. (1995).

Human cingulate cortex: surface features, flat maps, and cytoarchitecture. The Journal of comparative neurology, 359(3), 490-506. [PubMed:7499543] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Seitz, R.J., Roland, P.E., Bohm, C., Greitz, T., & Stone-Elander, S. (1991).

Somatosensory Discrimination of Shape: Tactile Exploration and Cerebral Activation. The European journal of neuroscience, 3(6), 481-492. [PubMed:12106480] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Seitz, R.J., & Roland, P.E. (1992).

Vibratory stimulation increases and decreases the regional cerebral blood flow and oxidative metabolism: a positron emission tomography (PET) study. Acta neurologica Scandinavica, 86(1), 60-7. [PubMed:1519476] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Richer, F., Martinez, M., Robert, M., Bouvier, G., & Saint-Hilaire, J.M. (1993).

Stimulation of human somatosensory cortex: tactile and body displacement perceptions in medial regions. Experimental brain research, 93(1), 173-6. [PubMed:8467887] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 14.0 14.1

Paus, T. (2001).

Primate anterior cingulate cortex: where motor control, drive and cognition interface. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 2(6), 417-24. [PubMed:11389475] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Bush, G., Luu, P., & Posner, M.I. (2000).

Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends in cognitive sciences, 4(6), 215-222. [PubMed:10827444] [WorldCat] - ↑

Polli, F.E., Barton, J.J., Cain, M.S., Thakkar, K.N., Rauch, S.L., & Manoach, D.S. (2005).

Rostral and dorsal anterior cingulate cortex make dissociable contributions during antisaccade error commission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(43), 15700-5. [PubMed:16227444] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5

Vogt, B.A., & Pandya, D.N. (1987).

Cingulate cortex of the rhesus monkey: II. Cortical afferents. The Journal of comparative neurology, 262(2), 271-89. [PubMed:3624555] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7

Morecraft, R.J., & Van Hoesen, G.W. (1998).

Convergence of limbic input to the cingulate motor cortex in the rhesus monkey. Brain research bulletin, 45(2), 209-32. [PubMed:9443842] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Morecraft, R.J., & Van Hoesen, G.W. (1993).

Frontal granular cortex input to the cingulate (M3), supplementary (M2) and primary (M1) motor cortices in the rhesus monkey. The Journal of comparative neurology, 337(4), 669-89. [PubMed:8288777] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Lu, M.T., Preston, J.B., & Strick, P.L. (1994).

Interconnections between the prefrontal cortex and the premotor areas in the frontal lobe. The Journal of comparative neurology, 341(3), 375-92. [PubMed:7515081] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Takada, M., Nambu, A., Hatanaka, N., Tachibana, Y., Miyachi, S., Taira, M., & Inase, M. (2004).

Organization of prefrontal outflow toward frontal motor-related areas in macaque monkeys. The European journal of neuroscience, 19(12), 3328-42. [PubMed:15217388] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3

Hatanaka, N., Tokuno, H., Hamada, I., Inase, M., Ito, Y., Imanishi, M., ..., & Takada, M. (2003).

Thalamocortical and intracortical connections of monkey cingulate motor areas. The Journal of comparative neurology, 462(1), 121-38. [PubMed:12761828] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Morecraft, R.J., Stilwell-Morecraft, K.S., & Rossing, W.R. (2004).

The motor cortex and facial expression: new insights from neuroscience. The neurologist, 10(5), 235-49. [PubMed:15335441] [WorldCat] - ↑

Vogt, B.A., Pandya, D.N., & Rosene, D.L. (1987).

Cingulate cortex of the rhesus monkey: I. Cytoarchitecture and thalamic afferents. The Journal of comparative neurology, 262(2), 256-70. [PubMed:3624554] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Gaspar, P., Berger, B., Febvret, A., Vigny, A., & Henry, J.P. (1989).

Catecholamine innervation of the human cerebral cortex as revealed by comparative immunohistochemistry of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase. The Journal of comparative neurology, 279(2), 249-71. [PubMed:2563268] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Williams, S.M., & Goldman-Rakic, P.S. (1993).

Characterization of the dopaminergic innervation of the primate frontal cortex using a dopamine-specific antibody. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 3(3), 199-222. [PubMed:8100725] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Muakkassa, K.F., & Strick, P.L. (1979).

Frontal lobe inputs to primate motor cortex: evidence for four somatotopically organized 'premotor' areas. Brain research, 177(1), 176-82. [PubMed:115545] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4

Wang, Y., Shima, K., Sawamura, H., & Tanji, J. (2001).

Spatial distribution of cingulate cells projecting to the primary, supplementary, and pre-supplementary motor areas: a retrograde multiple labeling study in the macaque monkey. Neuroscience research, 39(1), 39-49. [PubMed:11164252] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Morecraft, R.J., & Van Hoesen, G.W. (1992).

Cingulate input to the primary and supplementary motor cortices in the rhesus monkey: evidence for somatotopy in areas 24c and 23c. The Journal of comparative neurology, 322(4), 471-89. [PubMed:1383283] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2

Luppino, G., Matelli, M., Camarda, R., & Rizzolatti, G. (1993).

Corticocortical connections of area F3 (SMA-proper) and area F6 (pre-SMA) in the macaque monkey. The Journal of comparative neurology, 338(1), 114-40. [PubMed:7507940] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Kurata, K. (1991).

Corticocortical inputs to the dorsal and ventral aspects of the premotor cortex of macaque monkeys. Neuroscience research, 12(1), 263-80. [PubMed:1721118] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3

Morecraft, R.J., McNeal, D.W., Stilwell-Morecraft, K.S., Gedney, M., Ge, J., Schroeder, C.M., & van Hoesen, G.W. (2007).

Amygdala interconnections with the cingulate motor cortex in the rhesus monkey. The Journal of comparative neurology, 500(1), 134-65. [PubMed:17099887] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

SHOWERS, M.J. (1959).

The cingulate gyrus: additional motor area and cortical autonomic regulator. The Journal of comparative neurology, 112, 231-301. [PubMed:14446213] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

PENFIELD, W., & WELCH, K. (1951).

The supplementary motor area of the cerebral cortex; a clinical and experimental study. A.M.A. archives of neurology and psychiatry, 66(3), 289-317. [PubMed:14867993] [WorldCat] - ↑

Luppino, G., Matelli, M., Camarda, R.M., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (1991).

Multiple representations of body movements in mesial area 6 and the adjacent cingulate cortex: an intracortical microstimulation study in the macaque monkey. The Journal of comparative neurology, 311(4), 463-82. [PubMed:1757598] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 36.0 36.1

Shima, K., Aya, K., Mushiake, H., Inase, M., Aizawa, H., & Tanji, J. (1991).

Two movement-related foci in the primate cingulate cortex observed in signal-triggered and self-paced forelimb movements. Journal of neurophysiology, 65(2), 188-202. [PubMed:2016637] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 37.0 37.1

Isomura, Y., Ito, Y., Akazawa, T., Nambu, A., & Takada, M. (2003).

Neural coding of "attention for action" and "response selection" in primate anterior cingulate cortex. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 23(22), 8002-12. [PubMed:12954861] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Russo, G.S., Backus, D.A., Ye, S., & Crutcher, M.D. (2002).

Neural activity in monkey dorsal and ventral cingulate motor areas: comparison with the supplementary motor area. Journal of neurophysiology, 88(5), 2612-29. [PubMed:12424298] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 39.0 39.1

Shima, K., & Tanji, J. (1998).

Role for cingulate motor area cells in voluntary movement selection based on reward. Science (New York, N.Y.), 282(5392), 1335-8. [PubMed:9812901] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Niki, H., & Watanabe, M. (1979).

Prefrontal and cingulate unit activity during timing behavior in the monkey. Brain research, 171(2), 213-24. [PubMed:111772] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 41.0 41.1

Ito, S., Stuphorn, V., Brown, J.W., & Schall, J.D. (2003).

Performance monitoring by the anterior cingulate cortex during saccade countermanding. Science (New York, N.Y.), 302(5642), 120-2. [PubMed:14526085] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hoshi, E., Sawamura, H., & Tanji, J. (2005).

Neurons in the rostral cingulate motor area monitor multiple phases of visuomotor behavior with modest parametric selectivity. Journal of neurophysiology, 94(1), 640-56. [PubMed:15703223] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Procyk, E., Tanaka, Y.L., & Joseph, J.P. (2000).

Anterior cingulate activity during routine and non-routine sequential behaviors in macaques. Nature neuroscience, 3(5), 502-8. [PubMed:10769392] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Kennerley, S.W., Walton, M.E., Behrens, T.E., Buckley, M.J., & Rushworth, M.F. (2006).

Optimal decision making and the anterior cingulate cortex. Nature neuroscience, 9(7), 940-7. [PubMed:16783368] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Quilodran, R., Rothé, M., & Procyk, E. (2008).

Behavioral shifts and action valuation in the anterior cingulate cortex. Neuron, 57(2), 314-25. [PubMed:18215627] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Shidara, M., & Richmond, B.J. (2002).

Anterior cingulate: single neuronal signals related to degree of reward expectancy. Science (New York, N.Y.), 296(5573), 1709-11. [PubMed:12040201] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Amiez, C., Joseph, J.P., & Procyk, E. (2006).

Reward encoding in the monkey anterior cingulate cortex. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 16(7), 1040-55. [PubMed:16207931] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 48.0 48.1

Seo, H., & Lee, D. (2007).

Temporal filtering of reward signals in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex during a mixed-strategy game. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 27(31), 8366-77. [PubMed:17670983] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hayden, B.Y., Pearson, J.M., & Platt, M.L. (2009).

Fictive reward signals in the anterior cingulate cortex. Science (New York, N.Y.), 324(5929), 948-50. [PubMed:19443783] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Matsumoto, M., Matsumoto, K., Abe, H., & Tanaka, K. (2007).

Medial prefrontal cell activity signaling prediction errors of action values. Nature neuroscience, 10(5), 647-56. [PubMed:17450137] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 51.0 51.1

Kennerley, S.W., & Wallis, J.D. (2009).

Evaluating choices by single neurons in the frontal lobe: outcome value encoded across multiple decision variables. The European journal of neuroscience, 29(10), 2061-73. [PubMed:19453638] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Frith, C.D., Friston, K., Liddle, P.F., & Frackowiak, R.S. (1991).

Willed action and the prefrontal cortex in man: a study with PET. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 244(1311), 241-6. [PubMed:1679944] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ullsperger, M., & von Cramon, D.Y. (2001).

Subprocesses of performance monitoring: a dissociation of error processing and response competition revealed by event-related fMRI and ERPs. NeuroImage, 14(6), 1387-401. [PubMed:11707094] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Holroyd, C.B., Nieuwenhuis, S., Yeung, N., Nystrom, L., Mars, R.B., Coles, M.G., & Cohen, J.D. (2004).

Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex shows fMRI response to internal and external error signals. Nature neuroscience, 7(5), 497-8. [PubMed:15097995] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Walton, M.E., Devlin, J.T., & Rushworth, M.F. (2004).

Interactions between decision making and performance monitoring within prefrontal cortex. Nature neuroscience, 7(11), 1259-65. [PubMed:15494729] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Botvinick, M.M., Braver, T.S., Barch, D.M., Carter, C.S., & Cohen, J.D. (2001).

Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological review, 108(3), 624-52. [PubMed:11488380] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Carter, C.S., Braver, T.S., Barch, D.M., Botvinick, M.M., Noll, D., & Cohen, J.D. (1998).

Anterior cingulate cortex, error detection, and the online monitoring of performance. Science (New York, N.Y.), 280(5364), 747-9. [PubMed:9563953] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Botvinick, M.M., Cohen, J.D., & Carter, C.S. (2004).

Conflict monitoring and anterior cingulate cortex: an update. Trends in cognitive sciences, 8(12), 539-46. [PubMed:15556023] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Nakamura, K., Roesch, M.R., & Olson, C.R. (2005).

Neuronal activity in macaque SEF and ACC during performance of tasks involving conflict. Journal of neurophysiology, 93(2), 884-908. [PubMed:15295008] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Paus, T., Petrides, M., Evans, A.C., & Meyer, E. (1993).

Role of the human anterior cingulate cortex in the control of oculomotor, manual, and speech responses: a positron emission tomography study. Journal of neurophysiology, 70(2), 453-69. [PubMed:8410148] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Turken, A.U., & Swick, D. (1999).

Response selection in the human anterior cingulate cortex. Nature neuroscience, 2(10), 920-4. [PubMed:10491614] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Yoshida, K., Saito, N., Iriki, A., & Isoda, M. (2011).

Representation of others' action by neurons in monkey medial frontal cortex. Current biology : CB, 21(3), 249-53. [PubMed:21256015] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Yoshida, K., Saito, N., Iriki, A., & Isoda, M. (2012).

Social error monitoring in macaque frontal cortex. Nature neuroscience, 15(9), 1307-12. [PubMed:22864610] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2

Devinsky, O., Morrell, M.J., & Vogt, B.A. (1995).

Contributions of anterior cingulate cortex to behaviour. Brain : a journal of neurology, 118 ( Pt 1), 279-306. [PubMed:7895011] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

NIELSEN, J.M., & JACOBS, L.L. (1951).

Bilateral lesions of the anterior cingulate gyri; report of case. Bulletin of the Los Angeles Neurological Society, 16(2), 231-4. [PubMed:14839354] [WorldCat] - ↑

Németh, G., Hegedüs, K., & Molnár, L. (1988).

Akinetic mutism associated with bicingular lesions: clinicopathological and functional anatomical correlates. European archives of psychiatry and neurological sciences, 237(4), 218-22. [PubMed:2849547] [WorldCat] - ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2

Greenberg, B.D., Rauch, S.L., & Haber, S.N. (2010).

Invasive circuitry-based neurotherapeutics: stereotactic ablation and deep brain stimulation for OCD. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 35(1), 317-36. [PubMed:19759530] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Schoene-Bake, J.C., Parpaley, Y., Weber, B., Panksepp, J., Hurwitz, T.A., & Coenen, V.A. (2010).

Tractographic analysis of historical lesion surgery for depression. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 35(13), 2553-63. [PubMed:20736994] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 69.0 69.1

Milad, M.R., & Rauch, S.L. (2012).

Obsessive-compulsive disorder: beyond segregated cortico-striatal pathways. Trends in cognitive sciences, 16(1), 43-51. [PubMed:22138231] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Taylor, S.F., & Liberzon, I. (2007).

Neural correlates of emotion regulation in psychopathology. Trends in cognitive sciences, 11(10), 413-8. [PubMed:17928261] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Shin, L.M., & Liberzon, I. (2010).

The neurocircuitry of fear, stress, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 35(1), 169-91. [PubMed:19625997] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Goldstein, R.Z., Craig, A.D., Bechara, A., Garavan, H., Childress, A.R., Paulus, M.P., & Volkow, N.D. (2009).

The neurocircuitry of impaired insight in drug addiction. Trends in cognitive sciences, 13(9), 372-80. [PubMed:19716751] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Garavan, H., & Stout, J.C. (2005).

Neurocognitive insights into substance abuse. Trends in cognitive sciences, 9(4), 195-201. [PubMed:15808502] [WorldCat] [DOI]

(執筆者:吉田今日子、磯田昌岐 担当編集委員:伊佐正)