補足眼野

吉田 今日子、磯田 昌岐

関西医科大学

DOI:10.14931/bsd.2087 原稿受付日:2012年7月3日 原稿完成日:2015年12月22日

担当編集委員:田中 啓治(独立行政法人理化学研究所 脳科学総合研究センター)

英語名: supplementary eye field 独:supplementäres Augenfeld 英略語:SEF

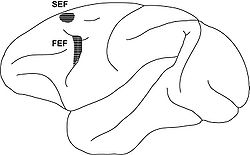

SEF, supplementary eye field(補足眼野)。FEF, frontal eye field(前頭眼野)。

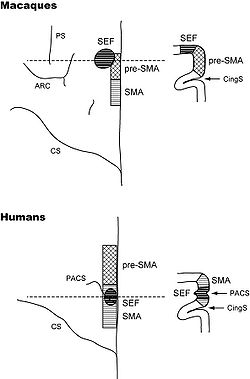

上段はサルの前頭葉、下段はヒトの前頭葉を示す。いずれも、左側は上から眺めた場合の模式図を示し(左半球)、右側は点線を通る冠状断面を示す。SMA, supplementary motor area;PS, principal sulcus(主溝);ARC, arcuate sulcus(弓状溝);CS, central sulcus(中心溝);PACS, paracentral sulcus(中心傍溝);CingS, cingulate sulcus(帯状溝)。

補足眼野は、大脳皮質に存在する眼球運動野である。前頭眼野や上丘に直接投射し、この領域を電気刺激すると比較的低閾値で急速眼球運動や滑動性眼球運動が誘発される。補足眼野の生理機能としては、とくに眼球運動の認知的制御が重要である。

補足眼野とは

補足眼野は大脳皮質前頭葉の背内側部に存在する眼球運動野である(図1)。1987年にSchlagらによってサルの脳において命名された[1]。しかし、既にその約半世紀以上も前に、脳外科医のPenfieldはヒトの手術中に補足運動野を電気刺激し、その前方部から眼球運動が誘発されることを報告していた[2] [3]。また、BrinkmanとPorterも、眼球運動に伴って活動する細胞をサルの補足運動野の吻側部に見出していた[4]。Schlagらは微小電気刺激法と単一神経細胞記録法を用いた系統的実験を行い、比較的低い強度(50μA以下)の電気刺激で急速眼球運動(サッケード、saccade)が誘発され、サッケード関連活動を示す神経細胞が多数存在する領域を同定し、補足眼野と命名した[1] [5]。「Evidence for a supplementary eye field」というタイトルで発表されたその論文には、前頭眼野とは異なる補足眼野の生理学的特徴として、(1) 電気刺激で誘発されるサッケードの潜時が前頭眼野よりも長い、(2) 誘発されるサッケードがしばしば特定の空間部位に収束する(goal-directedあるいはconverging)、(3) 神経活動の上昇が自発サッケードの開始に長く先行する、などが記載されている。

構造

肉眼解剖

前頭眼野(frontal eye field: FEF)とともに前頭葉の眼球運動中枢を構成する(図1)。ヒトの補足眼野は補足運動野内に存在し、上肢領域の前方に位置する[6] [7](図2)。解剖学的同定には中心傍溝がよい指標となる[8](図2)。一方、サルの補足眼野は補足運動野内には存在せず、前補足運動野と隣接してその背外側部に位置する[9](図2)。Matelliらの分類ではF7、特にその内側前方部分に相当する[10]。

入出力

補足眼野は、大脳皮質の眼球運動野である前頭眼野や外側頭頂間野(LIP野)との解剖学的結合に加え、前頭連合野との結合が豊富である[11] [12] [13] [14]。また、線条体、視床、上丘、脳幹諸核など、皮質下の視覚・眼球運動関連領野との結合が強い[11] [15] [16] [17]。補足眼野は、MST野、STSの多感覚領域、LIP野からの入力をうけるが、前頭眼野と比べると、その他の視覚前野からの入力は乏しい[11] [13]。特に、いわゆる腹側視覚系はほとんど補足眼野に入力しないようである[13]。一方、運動前野や補足運動野との結合は補足眼野の方が豊富である[11]。

生理機能

サッケード符号化の基準座標

前頭眼野や上丘(superior colliculus)を電気刺激すると一定のベクトル成分をもつサッケード(constant-vector saccades)が誘発されるのに対し、補足眼野の電気刺激ではconstant-vector saccades以外に、特定の空間部位へ収束するサッケード(goal-directed saccadesあるいはconverging saccades)が誘発される[1]。誘発サッケードの方向性に関する2領域間の機能的差異については異論もあるが[18]、その後の研究によっても、補足眼野内の刺激部位に応じてconstant-vector saccadesやgoal-directed saccadesが誘発されることが確認された[19]。これらの電気刺激結果は、補足眼野細胞が網膜中心座標に加え、非網膜中心座標(頭部・身体・外界中心座標の総称)を使ってサッケードをコードしていることを示唆する。頭部の運動に自由度をもたせて行った電気刺激実験の結果によれば、補足眼野で用いられる座標系は頭部中心座標が主体であった[20]。一方、Olsonらは補足眼野の細胞活動を解析し、同部のサッケードのコーディングが、標的となる視物体を中心とした座標系object-centered coordinateで行われることを発見した[21]。Olsonらの最新の研究結果は、補足眼野の基準座標系が細胞によって異なることを示唆している[22]。

電気刺激がサッケード遂行に及ぼす効果

電気刺激で誘発されるサッケードに関する上記の議論は、補足眼野で用いられる運動の基準座標と関連付けられたものであったが、それら以外にも補足眼野の電気刺激はサッケードの遂行やプランニングに対して顕著な効果をもたらす。サッケードの準備期間中で、GO信号が与えられる直前に電気刺激を行うと、生成すべきサッケードが刺激部位とは反対側へ向う場合にはその運動の反応時間が短縮する[23]。対照的に、GO信号の直後に加えた電気刺激では両側性にサッケードが抑制され(ただし同側優位のことが多い)、反応時間が延長する。これらの効果は補足眼野近傍に存在する前補足運動野への電気刺激効果と酷似しているが[24]、得られる効果の空間選択性は補足眼野の方が高い[25]。連続して提示される2つの視覚刺激の順序を記憶し、それに従って連続したサッケードを行うよう要求された課題では、記憶期間中に加えた電気刺激によって課題成績が悪化した[26]。さらに、サッケードの指令撤回課題(saccade countermanding task)遂行中に補足眼野を電気刺激すると、サッケードの生成を中止すべき試行において成績が向上した[27]。これは既に述べた電気刺激の反応時間遅延効果による可能性も考えられるが、同じ部位を同じパラメーターで電気刺激しても、視覚誘導性サッケード課題では反応時間の延長は認められなかった[27]。

サッケードの認知的制御

補足眼野は、サッケードの認知的制御への関与が大きいと考えられている。特に、視物体とサッケード方向の連合学習[28]、アンチサッケード(視物体とは反対方向へ向うサッケード)の生成[29]、コンフリクト(複数の運動プログラムが拮抗している状態)の検出[30](ただし、サッケード関連活動の修飾という形をとることが多い[31])、サッケード遂行後に受け取る報酬や報酬予測誤差の表現[30] [32] [33] [34]、サッケードの順序制御[35] [36] [37] [38] [39]、数百ミリ秒オーダーの待機時間経過処理[39], [40]、手と眼の協調運動制御[41]、報酬に基づくサッケード方向の選択過程[42]への関与が重要である。補足眼野の細胞応答は前頭眼野のそれよりもかなり状況依存的である。このような補足眼野の広範囲に及ぶ機能を一元的に説明する機能仮説は、現在までのところ提唱されていない。

補足眼野は、前頭前野のように上丘や脳幹へ直接投射するが[11] [15] [16]、サッケード生成への関与は前頭眼野よりも間接的であると考えられている。これは、補足眼野の電気刺激で誘発されるサッケードの閾値が前頭眼野のそれよりも高いこと[18] [43]、補足眼野の局所病変では単発サッケードの遂行がほとんど障害されないこと[44], [45]、サッケードの生成や中止の指示に対する補足眼野細胞の応答が、実際に生成や中止に関与するには遅すぎること[46]、といった研究結果により支持される。補足眼野は、サッケードの生成・開始に直接関与するというよりは、サッケードの内発的生成過程、あるいはプランニングやモニタリング過程など、より複雑で認知的な制御を必要とする行動局面において使われていると考えた方がよい。既に述べたように、単純なサッケードの発現に対する補足眼野病変の影響は極めて限定的である一方、より複雑で状況依存的なサッケードの発現に対しては顕著な障害効果をもたらす[44] [45] [47] [48]。また、動機づけにもとづく自発性サッケード生成においては、補足眼野の活動が前頭眼野の活動に先行することも、上記の考え方と合致する[6] [42]。

滑動性眼球運動の制御

眼球運動には、これまで述べてきたサッケード運動とは別に、比較的ゆっくりと動く視標を網膜中心窩で捉え、それを追跡する滑動性眼球運動(smooth pursuit)がある。補足眼野には滑動性眼球運動に伴って活動する細胞も存在する[49] [50] [51]。各細胞は運動方向に関するpreferred directionを有するが[49]、補足眼野全体でみると全ての方向がカバーされている[51]。一方、電気刺激を加えると反対側へ向かう滑動性眼球運動が誘発される[52]。また、サッケードや滑動性眼球運動が誘発されない部位であっても、予測的な滑動性眼球運動が促進されうる[53]。前頭眼野細胞と同様に、補足眼野の滑動性眼球運動関連細胞の多くは前庭入力を受ける[51]。一方、前頭眼野と比べ眼球速度や視線速度をコードする細胞、あるいは輻輳運動に関連する細胞の割合は少ない[51]。視覚刺激の色と運動方向の記憶にもとづいて眼球運動を行うか否かを判断し、行う場合には正しい方向に滑動性眼球運動を生成することを要求された場合、補足眼野細胞の多くは視覚刺激情報の記憶保持や運動の不実行に関連していた[54]。前頭眼野ではそのような細胞は少数で、方向選択的な滑動性眼球運動の実行と関連する細胞が多かった[55]。この課題を遂行中に両側の補足眼野の働きを一過性にブロックすると、滑動性眼球運動の初期成分やcatch-up saccadesが遅延し、運動方向の誤りが増加し、運動を行うべきか否かの判断ミスが増加した[54]。他方、前頭眼野の一過性機能ブロックでは滑動性眼球運動の速度が低下した。以上の結果から、滑動性眼球運動の制御においても前頭眼野と補足眼野の機能的異差があることが示唆される。

関連項目

参考文献

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2

Schlag, J., & Schlag-Rey, M. (1987).

Evidence for a supplementary eye field. Journal of neurophysiology, 57(1), 179-200. [PubMed:3559671] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ Penfield, W. & Welch, K.

The supplementary motor area in the cerebral cortex of man.

Transactions of the American Neurological Association 74, 179-184 (1949) - ↑

PENFIELD, W., & WELCH, K. (1951).

The supplementary motor area of the cerebral cortex; a clinical and experimental study. A.M.A. archives of neurology and psychiatry, 66(3), 289-317. [PubMed:14867993] [WorldCat] - ↑

Brinkman, C., & Porter, R. (1979).

Supplementary motor area in the monkey: activity of neurons during performance of a learned motor task. Journal of neurophysiology, 42(3), 681-709. [PubMed:107282] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Schlag, J., & Schlag-Rey, M. (1985).

Unit activity related to spontaneous saccades in frontal dorsomedial cortex of monkey. Experimental brain research, 58(1), 208-11. [PubMed:3987850] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 6.0 6.1

Yamamoto, J., Ikeda, A., Satow, T., Matsuhashi, M., Baba, K., Yamane, F., ..., & Shibasaki, H. (2004).

Human eye fields in the frontal lobe as studied by epicortical recording of movement-related cortical potentials. Brain : a journal of neurology, 127(Pt 4), 873-87. [PubMed:14960503] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Sumner, P., Nachev, P., Morris, P., Peters, A.M., Jackson, S.R., Kennard, C., & Husain, M. (2007).

Human medial frontal cortex mediates unconscious inhibition of voluntary action. Neuron, 54(5), 697-711. [PubMed:17553420] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Grosbras, M.H., Lobel, E., Van de Moortele, P.F., LeBihan, D., & Berthoz, A. (1999).

An anatomical landmark for the supplementary eye fields in human revealed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 9(7), 705-11. [PubMed:10554993] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tanji, J. (1994).

The supplementary motor area in the cerebral cortex. Neuroscience research, 19(3), 251-68. [PubMed:8058203] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Luppino, G., Matelli, M., Camarda, R.M., Gallese, V., & Rizzolatti, G. (1991).

Multiple representations of body movements in mesial area 6 and the adjacent cingulate cortex: an intracortical microstimulation study in the macaque monkey. The Journal of comparative neurology, 311(4), 463-82. [PubMed:1757598] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4

Huerta, M.F., & Kaas, J.H. (1990).

Supplementary eye field as defined by intracortical microstimulation: connections in macaques. The Journal of comparative neurology, 293(2), 299-330. [PubMed:19189718] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Schall, J.D., Morel, A., & Kaas, J.H. (1993).

Topography of supplementary eye field afferents to frontal eye field in macaque: implications for mapping between saccade coordinate systems. Visual neuroscience, 10(2), 385-93. [PubMed:7683486] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2

Schall, J.D., Morel, A., King, D.J., & Bullier, J. (1995).

Topography of visual cortex connections with frontal eye field in macaque: convergence and segregation of processing streams. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 15(6), 4464-87. [PubMed:7540675] [WorldCat] - ↑

Wang, Y., Isoda, M., Matsuzaka, Y., Shima, K., & Tanji, J. (2005).

Prefrontal cortical cells projecting to the supplementary eye field and presupplementary motor area in the monkey. Neuroscience research, 53(1), 1-7. [PubMed:15992955] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 15.0 15.1

Shook, B.L., Schlag-Rey, M., & Schlag, J. (1988).

Direct projection from the supplementary eye field to the nucleus raphe interpositus. Experimental brain research, 73(1), 215-8. [PubMed:2463179] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 16.0 16.1

Shook, B.L., Schlag-Rey, M., & Schlag, J. (1990).

Primate supplementary eye field: I. Comparative aspects of mesencephalic and pontine connections. The Journal of comparative neurology, 301(4), 618-42. [PubMed:2273101] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Shook, B.L., Schlag-Rey, M., & Schlag, J. (1991).

Primate supplementary eye field. II. Comparative aspects of connections with the thalamus, corpus striatum, and related forebrain nuclei. The Journal of comparative neurology, 307(4), 562-83. [PubMed:1869632] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 18.0 18.1

Russo, G.S., & Bruce, C.J. (1993).

Effect of eye position within the orbit on electrically elicited saccadic eye movements: a comparison of the macaque monkey's frontal and supplementary eye fields. Journal of neurophysiology, 69(3), 800-18. [PubMed:8385196] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Park, J., Schlag-Rey, M., & Schlag, J. (2006).

Frames of reference for saccadic command tested by saccade collision in the supplementary eye field. Journal of neurophysiology, 95(1), 159-70. [PubMed:16162836] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Martinez-Trujillo, J.C., Medendorp, W.P., Wang, H., & Crawford, J.D. (2004).

Frames of reference for eye-head gaze commands in primate supplementary eye fields. Neuron, 44(6), 1057-66. [PubMed:15603747] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Olson, C.R., & Gettner, S.N. (1995).

Object-centered direction selectivity in the macaque supplementary eye field. Science (New York, N.Y.), 269(5226), 985-8. [PubMed:7638625] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Moorman, D.E., & Olson, C.R. (2007).

Combination of neuronal signals representing object-centered location and saccade direction in macaque supplementary eye field. Journal of neurophysiology, 97(5), 3554-66. [PubMed:17329630] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fujii, N., Mushiake, H., Tamai, M., & Tanji, J. (1995).

Microstimulation of the supplementary eye field during saccade preparation. Neuroreport, 6(18), 2565-8. [PubMed:8741764] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Isoda, M. (2005).

Context-dependent stimulation effects on saccade initiation in the presupplementary motor area of the monkey. Journal of neurophysiology, 93(5), 3016-22. [PubMed:15703225] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Yang, S.N., Heinen, S.J., & Missal, M. (2008).

The effects of microstimulation of the dorsomedial frontal cortex on saccade latency. Journal of neurophysiology, 99(4), 1857-70. [PubMed:18216220] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Histed, M.H., & Miller, E.K. (2006).

Microstimulation of frontal cortex can reorder a remembered spatial sequence. PLoS biology, 4(5), e134. [PubMed:16620152] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 27.0 27.1

Stuphorn, V., & Schall, J.D. (2006).

Executive control of countermanding saccades by the supplementary eye field. Nature neuroscience, 9(7), 925-31. [PubMed:16732274] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Chen, L.L., & Wise, S.P. (1995).

Neuronal activity in the supplementary eye field during acquisition of conditional oculomotor associations. Journal of neurophysiology, 73(3), 1101-21. [PubMed:7608758] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Schlag-Rey, M., Amador, N., Sanchez, H., & Schlag, J. (1997).

Antisaccade performance predicted by neuronal activity in the supplementary eye field. Nature, 390(6658), 398-401. [PubMed:9389478] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 30.0 30.1

Stuphorn, V., Taylor, T.L., & Schall, J.D. (2000).

Performance monitoring by the supplementary eye field. Nature, 408(6814), 857-60. [PubMed:11130724] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Nakamura, K., Roesch, M.R., & Olson, C.R. (2005).

Neuronal activity in macaque SEF and ACC during performance of tasks involving conflict. Journal of neurophysiology, 93(2), 884-908. [PubMed:15295008] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Amador, N., Schlag-Rey, M., & Schlag, J. (2000).

Reward-predicting and reward-detecting neuronal activity in the primate supplementary eye field. Journal of neurophysiology, 84(4), 2166-70. [PubMed:11024104] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Uchida, Y., Lu, X., Ohmae, S., Takahashi, T., & Kitazawa, S. (2007).

Neuronal activity related to reward size and rewarded target position in primate supplementary eye field. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 27(50), 13750-5. [PubMed:18077686] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

So, N., & Stuphorn, V. (2012).

Supplementary eye field encodes reward prediction error. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 32(9), 2950-63. [PubMed:22378869] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Lu, X., Matsuzawa, M., & Hikosaka, O. (2002).

A neural correlate of oculomotor sequences in supplementary eye field. Neuron, 34(2), 317-25. [PubMed:11970872] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Isoda, M., & Tanji, J. (2002).

Cellular activity in the supplementary eye field during sequential performance of multiple saccades. Journal of neurophysiology, 88(6), 3541-5. [PubMed:12466467] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Isoda, M., & Tanji, J. (2003).

Contrasting neuronal activity in the supplementary and frontal eye fields during temporal organization of multiple saccades. Journal of neurophysiology, 90(5), 3054-65. [PubMed:12904333] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Berdyyeva, T.K., & Olson, C.R. (2009).

Monkey supplementary eye field neurons signal the ordinal position of both actions and objects. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 29(3), 591-9. [PubMed:19158286] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 39.0 39.1

Berdyyeva, T.K., & Olson, C.R. (2011).

Relation of ordinal position signals to the expectation of reward and passage of time in four areas of the macaque frontal cortex. Journal of neurophysiology, 105(5), 2547-59. [PubMed:21389312] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ohmae, S., Lu, X., Takahashi, T., Uchida, Y., & Kitazawa, S. (2008).

Neuronal activity related to anticipated and elapsed time in macaque supplementary eye field. Experimental brain research, 184(4), 593-8. [PubMed:18064442] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Mushiake, H., Fujii, N., & Tanji, J. (1996).

Visually guided saccade versus eye-hand reach: contrasting neuronal activity in the cortical supplementary and frontal eye fields. Journal of neurophysiology, 75(5), 2187-91. [PubMed:8734617] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 42.0 42.1

Coe, B., Tomihara, K., Matsuzawa, M., & Hikosaka, O. (2002).

Visual and anticipatory bias in three cortical eye fields of the monkey during an adaptive decision-making task. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 22(12), 5081-90. [PubMed:12077203] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Tehovnik, E.J., & Sommer, M.A. (1997).

Electrically evoked saccades from the dorsomedial frontal cortex and frontal eye fields: a parametric evaluation reveals differences between areas. Experimental brain research, 117(3), 369-78. [PubMed:9438704] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 44.0 44.1

Schiller, P.H., & Chou, I.H. (1998).

The effects of frontal eye field and dorsomedial frontal cortex lesions on visually guided eye movements. Nature neuroscience, 1(3), 248-53. [PubMed:10195151] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 45.0 45.1

Sommer, M.A., & Tehovnik, E.J. (1999).

Reversible inactivation of macaque dorsomedial frontal cortex: effects on saccades and fixations. Experimental brain research, 124(4), 429-46. [PubMed:10090655] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Stuphorn, V., Brown, J.W., & Schall, J.D. (2010).

Role of supplementary eye field in saccade initiation: executive, not direct, control. Journal of neurophysiology, 103(2), 801-16. [PubMed:19939963] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Gaymard, B., Pierrot-Deseilligny, C., & Rivaud, S. (1990).

Impairment of sequences of memory-guided saccades after supplementary motor area lesions. Annals of neurology, 28(5), 622-6. [PubMed:2260848] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Husain, M., Parton, A., Hodgson, T.L., Mort, D., & Rees, G. (2003).

Self-control during response conflict by human supplementary eye field. Nature neuroscience, 6(2), 117-8. [PubMed:12536212] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 49.0 49.1

Heinen, S.J. (1995).

Single neuron activity in the dorsomedial frontal cortex during smooth pursuit eye movements. Experimental brain research, 104(2), 357-61. [PubMed:7672029] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Heinen, S.J., & Liu, M. (1997).

Single-neuron activity in the dorsomedial frontal cortex during smooth-pursuit eye movements to predictable target motion. Visual neuroscience, 14(5), 853-65. [PubMed:9364724] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3

Fukushima, J., Akao, T., Takeichi, N., Kurkin, S., Kaneko, C.R., & Fukushima, K. (2004).

Pursuit-related neurons in the supplementary eye fields: discharge during pursuit and passive whole body rotation. Journal of neurophysiology, 91(6), 2809-25. [PubMed:14711976] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tian, J.R., & Lynch, J.C. (1995).

Slow and saccadic eye movements evoked by microstimulation in the supplementary eye field of the cebus monkey. Journal of neurophysiology, 74(5), 2204-10. [PubMed:8592211] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Missal, M., & Heinen, S.J. (2004).

Supplementary eye fields stimulation facilitates anticipatory pursuit. Journal of neurophysiology, 92(2), 1257-62. [PubMed:15014104] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 54.0 54.1

Shichinohe, N., Akao, T., Kurkin, S., Fukushima, J., Kaneko, C.R., & Fukushima, K. (2009).

Memory and decision making in the frontal cortex during visual motion processing for smooth pursuit eye movements. Neuron, 62(5), 717-32. [PubMed:19524530] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fukushima, J., Akao, T., Shichinohe, N., Kurkin, S., Kaneko, C.R., & Fukushima, K. (2011).

Neuronal activity in the caudal frontal eye fields of monkeys during memory-based smooth pursuit eye movements: comparison with the supplementary eye fields. Cerebral cortex (New York, N.Y. : 1991), 21(8), 1910-24. [PubMed:21209120] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI]