「シンタキシン」の版間の差分

| (3人の利用者による、間の246版が非表示) | |||

| 1行目: | 1行目: | ||

<div align="right"> | <div align="right"> | ||

<font size="+1">[http://researchmap.jp/tnishiki/?lang=japanese 西木 禎一]</font><br> | <font size="+1">[http://researchmap.jp/tnishiki/?lang=japanese 西木 禎一]</font><br> | ||

''岡山大学 | ''岡山大学 大学院医歯薬学総合研究科 細胞生理学分野''<br> | ||

</div> | </div> | ||

英語名:syntaxin, 英略語:STX | |||

同義語:p35, HPC-1, synaptocanalin | 同義語:p35, HPC-1, synaptocanalin | ||

{{box|text= | {{box | ||

|text= シンタキシンは、細胞内[[小胞輸送]]において膜の融合に関わるタンパク質ファミリーおよびそのメンバーである。[[ヒト]]では、少なくとも19種類のアイソフォームが同定されている。シンタキシンファミリーメンバーの大部分が脳にも発現しているが、この項ではニューロンの機能の大きな特徴である神経伝達物質の放出を担うアイソフォーム1について述べる。}} | |||

}} | |||

== シンタキシンとは == | == シンタキシンとは == | ||

シンタキシン1は、[[シナプス小胞]]タンパク質[[シナプトタグミン]]と結合する分子量約35,000の内在性[[膜タンパク質]]p35Aおよびp35Bとして[[ラット]]脳可溶化画分から同定された<ref><pubmed> 1321498 </pubmed></ref>。シンタキシン1のAとBは異なる遺伝子によりコードされているが、どちらも288個のアミノ酸からなり、両者のアミノ酸配列は約80%の相同性をもつ。[[シナプス]]小胞のドッキングと[[開口放出]]に関わるとの予測から、「順番に整理して一緒に並べること」を意味する古代ギリシャ語σψνταξισ (syntaxis) にちなみ命名された。ほぼ同時期に複数のグループにより同定されたので、HPC-1<ref><pubmed>1587842 </pubmed></ref>あるいはsynaptocanalin<ref><pubmed>9137572</pubmed></ref>とも呼ばれる。 | |||

シンタキシンファミリーは、SNARE (soluble ''N''-etylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptorの略) と総称される[[膜融合]]関連タンパク質スーパーファミリーの一員でもある。SNAREは、輸送小胞に局在するv-SNARE (vはvesicularのv) と標的膜に存在するt-SNARE (tはtarget-membraneのt) の2種類に大別される<ref><pubmed>8455717</pubmed></ref>。シンタキシン1はその局在(後述)からt-SNAREに属するとともに、SNAREモチーフの中央にグルタミン残基を持つことから、そのアミノ酸一文字表記にならいQ-SNAREとも分類される<ref><pubmed>9861047</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

== 構造 == | == 構造 == | ||

[[ファイル:Syntaxin Fig1.png|300px|サムネイル|右|''' | [[ファイル:Syntaxin Fig1.png|300px|サムネイル|右|'''図1. シンタキシンのドメイン構造.''']] | ||

シンタキシン1は、4つのドメインがリンカーでつながれた構造をしている(図1)。アミノ末端のNペプチドモチーフ(1-19)は、Munc-18との結合に関わる(後述)<ref><pubmed>21139055</pubmed></ref>。二番目のHabcと呼ばれるドメイン(~27-146)では、3本のαへリックスが逆平行に結合し束になっている<ref><pubmed>9753330</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>10913252</pubmed></ref>。Habcに続くリンカーは非常にフレキシブルで<ref><pubmed>12680753</pubmed></ref>、Habcは次のH3ドメインに折り重なることよりSNARE複合体の膜融合能を制御する負の調節ドメインとして働く<ref><pubmed>10535962</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

シンタキシン1のカルボキシ末端側3分の1は、膜融合能を発揮するのに必要最小限の領域である。SNAREモチーフを含むH3ドメイン(~185-254)は、SNAP-25ならびにシナプトブレビンと結合し、膜融合能をもつSNARE複合体を形成する<ref><pubmed>9100028</pubmed></ref>。続く膜貫通ドメイン(266-288)は、[[細胞膜]]に埋め込まれているが貫通はしない<ref><pubmed>12761168</pubmed></ref>。これら両ドメインを含む組換えフラグメントを全長のSNAP-25ととともに再構成した人工脂質小胞は、シナプトブレビンを再構成した人工脂質小胞と自発的に融合する<ref><pubmed>9529252</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

モノメリックなシンタキシン1は、活性化状態と不活性状態を移行する<ref><pubmed>14668446</pubmed></ref>。活性化状態では、HabcとH3が解離したいわゆる開いた構造をとり、SNAP-25およびシナプトブレビンと結合できる。これに対し、HabcがH3に折り重なった閉じた構造になると不活性型となり、SNARE複合体を形成できない<ref><pubmed>18458823</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>10449403 </pubmed></ref>。 | |||

== 生体内および細胞内分布 == | == 生体内および細胞内分布 == | ||

シンタキシン1は神経系に特異的に発現する。組織染色において[[大脳皮質]]、[[海馬]]、[[小脳]]、脊髄、網膜のシナプスが豊富な領域に観察される<ref><pubmed>8361334</pubmed></ref>。有郭乳頭味蕾<ref><pubmed>17447252</pubmed></ref>、[[蝸牛]]内のコルチ器<ref><pubmed>10103074</pubmed></ref>、松果体細胞<ref><pubmed>8593674</pubmed></ref> にも存在する。神経系だけでなく、発生学的にニューロンと同じ外胚葉由来の副腎髄質にも発現している<ref><pubmed>7818508</pubmed></ref>。中枢神経系および末梢神経系の両方において、1Aと1Bの分布は異なる<ref><pubmed>10197765</pubmed></ref> <ref><pubmed>8996803</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

ニューロンにおいてシンタキシン1は、主に[[シナプス前膜]] | ニューロンにおいてシンタキシン1は、主に[[シナプス前膜]]を含む細胞膜内面に局在する一方、シナプス小胞膜にも認められる<ref><pubmed>8301329</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>7698978</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>23821748 </pubmed></ref>。小脳皮質においては、ほとんどの[[グルタミン酸]]作動性終末と、一部の[[GABA作動性]]シナプスに局在する<ref><pubmed>22094010 </pubmed></ref>。その他にも、視索上核のオキシトシンニューロンでは[[軸索終末]]だけでなく細胞体や樹状突起に発現が見られるとともに<ref><pubmed>21988098</pubmed></ref>、ヒヨコの[[毛様体神経節]]のHeld杯状シナプス前部<ref><pubmed>15102922</pubmed></ref>、[[カエル]]の運動[[神経終末]]<ref><pubmed>8963446</pubmed></ref>にも存在する。アストロサイトにも発現している<ref><pubmed>9098527</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>21656854</pubmed></ref>。 | ||

== 翻訳後修飾 == | == 翻訳後修飾 == | ||

シンタキシン1は、PKCおよび[[CaMKII]]<ref><pubmed>8876242</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>9930733</pubmed></ref> 、カゼインキナーゼ1および2<ref><pubmed> 11846792</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed> 1321498 </pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed> 9930733 </pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed> 10844023 </pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed> 15822905 </pubmed></ref>によりリン酸化される。[[PKA]]については議論が分かれている<ref><pubmed> 8876242 </pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>9930733 </pubmed></ref>。リン酸化以外に、ニトロ化<ref><pubmed> 10913827 </pubmed></ref>、Sニトロシル化<ref><pubmed> Palmer, Biochem J 413:479, 2008</pubmed></ref>、[[パルミトイル化]]<ref><pubmed> 19508429 </pubmed></ref>を受け、ユビキチン-[[プロテアソーム]]経路により分解される<ref><pubmed>12121982</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

== 結合タンパク質 == | == 結合タンパク質 == | ||

''in vitro''においてシンタキシン1は、約50種類ものタンパク質と結合することが示されている。ここでは、神経伝達物質の放出に関与しているものを中心に取上げる。 | |||

=== SNARE(SNAP-25およびシナプトブレビン) === | === SNARE(SNAP-25およびシナプトブレビン) === | ||

シンタキシン1は、同じくt- | シンタキシン1は、同じくt-SNAREであるSNAP-25と自身のH3ドメインを介し結合する<ref><pubmed>9100028</pubmed></ref>。会合比により2種類の複合体が存在する。1:1で結合したt-SNAREヘテロニ量体は、v-SNAREであるシナプトブレビン(別名VAMP)と結合しSNARE複合体を形成する。一方、シンタキシン二分子にSNAP-25が一分子結合した2:1複合体(通称)は、シナプトブレビンと結合できない<ref><pubmed>9346956</pubmed></ref>。したがって、[[シナプス前終末]]の放出部位では、別の分子により1:1複合体の状態が維持されていると予想される。 | ||

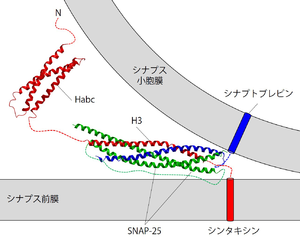

[[ファイル:Syntaxin Fig.png|300px|サムネイル|右|'''図2. 開口放出前に形成されるSNARE複合体の立体構造模式図.''' シンタキシンは赤で描いている。緑はSNAP-25を、青はシナプトブレビンをそれぞれ示す。円柱は膜貫通ドメインを表す。点線は執筆者が書き加えた領域である。]] | |||

[[ファイル:Syntaxin Fig.png|300px|サムネイル|右|''' | シンタキシン1、SNAP-25、およびシナプトブレビンが1:1:1の比で結合したSNARE複合体は、コイルドコイル構造をもつ<ref><pubmed>9759724</pubmed></ref>。よく目にするシナプス小胞膜と[[シナプス前]]膜との間で形成されているSNARE複合体の模式図は、シンタキシンのH3ドメインとSNAP-25およびシナプトブレビンの細胞質フラグメントからなる複合体の立体構造解析結果に膜貫通領域などを描き足したものである(図2)。組織を可溶化した後などに溶液中に存在するSNARE複合体は強固に結合しており、強力な界面活性剤に対しても耐性を持ち、SDS存在下でも煮沸しない限り解離しない<ref><pubmed>7957071</pubmed></ref>。 | ||

=== シナプトタグミン === | === シナプトタグミン === | ||

シンタキシン1は、H3ドメインを介して神経伝達物質放出のカルシウムイオンセンサーの最有力候補シナプトタグミン1と結合する<ref><pubmed>18275379</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>22068972</pubmed></ref>。カルシウムイオン非存在下では、シナプトタグミンのC<sub>2</sub>Bドメインと結合する<ref><pubmed>12496268</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>22008253 </pubmed></ref>。大腸菌で発現させた組換えタンパク質同士の結合は、結合実験に用いるフラグメントの大きさや付加するタグによって、特にカルシウムイオンの要求性に、大きな影響を受ける<ref><pubmed>8604041</pubmed></ref>。ある条件下ではシンタキシン1とシナプトタグミン1の結合はカルシウム依存性であり<ref><pubmed>7791877</pubmed></ref>、シナプトタグミンのC<sub>2</sub>Aドメインへのカルシウムイオンの結合が必須である<ref><pubmed>9010211</pubmed></ref>。しかし、C<sub>2</sub>Aのカルシウム結合能を欠失させた変異シナプトタグミンを発現させたニューロンで神経伝達物質の放出に異常が認められないことから<ref><pubmed>12110845</pubmed></ref>、シンタキシンとシナプトグミンのカルシウム依存性結合の伝達物質放出における意義は不明である。 | |||

===コンプレキシン === | ===コンプレキシン === | ||

シンタキシンは、コンプレキシン(別名シナフィン)とH3を介して結合する<ref><pubmed>7553862</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>9302098</pubmed></ref>。コンプレキシンは、SNARE複合体による膜融合を一時停止させる役割を持つとされるシナプス前終末タンパク質である<ref><pubmed>19164740</pubmed></ref>。コンプレキシンの中央部分とSNARE複合体の結合状態の立体構造が明らかにされている<ref><pubmed>11832227</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

=== Munc-18 === | === Munc-18 === | ||

小胞のドッキングあるいはプライミングに関与するMunc-18(別名n-Sec1)のシンタキシンへの結合は<ref><pubmed>8247129</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>8108429 </pubmed></ref>、当初SNARE複合体の形成を阻害するとされていた<ref><pubmed>8108429</pubmed></ref>。これは、単純化された結合実験において、シンタキシン1のNペプチドにMunc18が結合している時はその閉構造が安定化し<ref><pubmed>23561535</pubmed></ref>、SNAP-25と結合できないためである<ref><pubmed>18337752</pubmed></ref> 。しかしその後、Munc-18と結合したシンタキシン1でもMunc-13存在下では開構造へと変形し<ref><pubmed>10366611</pubmed></ref>、SNARE複合体を形成できることが明らかにされた(後述)<ref><pubmed>17002520</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>17301226</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>17264080</pubmed></ref>。このように、Munc-18は、シンタキシン1の開閉構造に応じた二種類の結合様式でモノメリックなシンタキシン1とSNARE複合体中のシンタキシン1の両方に結合することができる。シンタキシン1とMunc-18の結合は、両者のリン酸化<ref><pubmed>8631738</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>9478941</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>12730201</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>19748891</pubmed></ref>や、アラキドン酸<ref><pubmed>17363971</pubmed></ref>およびスフィンゴシン<ref><pubmed>19390577</pubmed></ref>により制御される。シンタキシンとMunc-18の複合体の立体構造も明らかにされている<ref><pubmed>10746715</pubmed></ref> 。 | |||

=== Munc-13 === | === Munc-13 === | ||

Munc-13は、シンタキシンを閉構造から開構造へ変換することで、Munc18と結合したシンタキシンをSNARE複合体が形成できるようにする<ref><pubmed>17645391</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>21499244</pubmed></ref> | Munc-13は、シンタキシンを閉構造から開構造へ変換することで、Munc18と結合したシンタキシンをSNARE複合体が形成できるようにする<ref><pubmed>17645391</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>21499244</pubmed></ref>。このタンパク質間相互作用は、シナプス小胞のドッキングおよびプライミングに関与しているとされている<ref><pubmed>18250196 </pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>11460165</pubmed></ref>。 | ||

=== カルシウムチャネル === | === [[カルシウムチャネル]] === | ||

シンタキシンは多様な[[カルシウムチャネル]]と結合する<ref><pubmed>10212477</pubmed></ref> | |||

<ref><pubmed>10414292</pubmed></ref> | <ref><pubmed>10414292</pubmed></ref> | ||

<ref><pubmed>12832834</pubmed></ref> | <ref><pubmed>12832834</pubmed></ref> | ||

。中でもN型 カルシウムチャネルとの結合は良く調べられていて<ref><pubmed>8119979</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>1334074</pubmed></ref>、チャネルの細胞質内ループ中のシンプリントsynprintと呼ばれる部位とシンタキシンのNペプチドがカルシウムイオン濃度依存性に結合する<ref><pubmed>7993624</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>12221094</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>8559250</pubmed></ref>。また、これとは別にシンタキシンの膜貫通領域とその直前の細胞質領域が調節に関与している<ref><pubmed>11087812</pubmed></ref>。。Gタンパク質によるカルシウムチャネルの機能調節は、シンタキシンとG<sub>β</sub>とG<sub>γ</sub>からなるヘテロ二量体との直接結合により促進される<ref><pubmed>10692440</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

<br> | |||

<br> | |||

その他にもシンタキシンは、[[CAPS]]、VAP-A、α-fodrin、CaMKII、granuphilin、staring、amisyn、D53、taxillin、各種伝達物質トランスポーター、Death-associated protein (DAP)キナーゼ、ある種のKチャネル、syntabulin、ミオシンVa、クラスC-Vps複合体、オトフェリン、HSP-70、IP3受容体、Mチャネル、DCC (deleted in colorectal cancer)、PRIP (phospholipase C-related but catalytically inactive protein)、CCCrel-1、cysteine-string protein (CSP) 、[[チューブリン]]、syncollin、presenilin-1、ダイナミン、α-SNAP、シナプトブレビン、syntaphilin、tomosyn、 | |||

あるいは[[dopamine transporter]]([[DAT]])/the receptor for activated C kinases (RACK1) と結合する。 | |||

== 機能 == | == 機能 == | ||

シナプス前膜に存在するシンタキシン1は、エンドサイトーシスを含め<ref><pubmed>23643538</pubmed></ref>シナプス小胞の循環のいくつかの過程に直接または間接的に関わる。その中でもカルシウム依存性の小胞開口放出過程における役割について最も研究が進んでおり、シンタキシン1はシナプス前膜と小胞膜との間でSNAP-25およびシナプトブレビンとSNARE複合体を形成し、両方の膜を限りなく近づけて融合させ神経伝達物質を開口放出させると考えられている<ref><pubmed>10219238</pubmed></ref>。[[マウス]]の内耳[[有毛細胞]]からの伝達物質放出には関与しないという例外はあるが<ref><pubmed>21378973</pubmed></ref>、実験材料として使われる多くの神経標本および開口放出のモデル細胞における伝達物質放出にはシンタキシン1が必須である<ref><pubmed>7818508</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>7609887</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>9692742</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>7612024</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>9342384</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

シンタキシン1は、開口放出に先立ちシナプス小胞や[[有芯小胞]]を放出部位へドッキングさせる。実際、カエルの[[神経筋接合部]]<ref><pubmed>14622203</pubmed></ref>ならびに副腎髄質クロマフィン細胞<ref><pubmed>17205130</pubmed></ref>においてシンタキシンを切断あるいは破壊すると小胞のドッキングが阻害される。一方、ニューロン間のシナプスではシンタキシンの機能を阻害してもドッキングに影響はない<ref><pubmed>14622203</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>17205130</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>9342384</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

刺激に応じた小胞の開口放出はカルシウム依存性だが、シンタキシン1を含むSNAREにはカルシウムイオン結合能はない。しかし、シンタキシン自身は、カルシウムチャネルへの結合を介して小胞を放出部位へドッキングさせる<ref><pubmed>18060067</pubmed></ref>。一方で、カルシウムチャネルの機能を抑制することから<ref><pubmed>8524397</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>10548106</pubmed></ref>、伝達物質放出のカルシウムイオンによる制御において相反する二種類の働きを併せ持つ<ref><pubmed>17215385</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

それ以外にも、開口放出時に形成されると考えられているフュージョンポアへの関与<ref><pubmed>15016962</pubmed></ref> 、神経突起の伸長<ref><pubmed>8698815</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>10900079</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>21593320</pubmed></ref>、学習と記憶に関与する可能性<ref><pubmed>8921297 </pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>9200718</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>9749751</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>20563839</pubmed></ref>が示唆されている。 | |||

== 疾患との関わり == | == 疾患との関わり == | ||

ボツリヌス中毒の主な症状である弛緩性麻痺は、運動神経終末からの[[アセチルコリン]]の放出阻害による。これは、中毒の原因である[[ボツリヌス菌]]が産生する毒素のもつタンパク質分解酵素活性によるSNAREの切断に起因する。7種類存在する[[ボツリヌス毒素]]の中、C型毒素はシンタキシ1をカルボキシ末端付近の1箇所、リシン残基とアラニン残基(1Aでは253番目と254番目、1Bでは252番目と253番目)の間で切断する<ref><pubmed>7901002</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>7737992</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

中枢ならびに末梢神経系疾患との関連性も示唆されている。統合失調症<ref><pubmed>15219469</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>19748077</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>21669024</pubmed></ref>、高機能[[自閉症]]<ref><pubmed>18593506</pubmed></ref>、脳虚血後<ref><pubmed>19344701</pubmed></ref>においてシンタキシン1の発現量が増加していることが報告されている。末梢神経障害による異痛症にシンタキシン1の発現低下が関与している可能性も言われている<ref><pubmed>21129445</pubmed></ref>。 | |||

== 遺伝子操作動物 == | == 遺伝子操作動物 == | ||

シンタキシン1Aの[[ノックアウトマウス]]は生育可能だが、[[ | シンタキシン1Aの[[ノックアウトマウス]]は生育可能だが、[[恐怖条件付け]]記憶の阻害に加え、[[セロトニン]]作動性神経系の異常と考えられる行動異常と[[視床下部-下垂体-副腎系]]の機能不全を呈す<ref><pubmed>16723534</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>20576034</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>21910766</pubmed></ref>。 | ||

これに対し、シンタキシン1Bのノックアウトマウスは生後2週間までしか生存できず、グルタミン酸あるいはGABAの放出においてシナプス小胞の正常な開口放出と即時放出可能プールの形成が阻害されている<ref><pubmed>24587181</pubmed></ref>。恒常的に開構造をとる変異シンタキシン1B遺伝子を強制発現させたノックインマウスは生育可能だが、2-3ヶ月齢で全身痙攣を呈し死にいたる<ref><pubmed>18703708</pubmed></ref>。[[ショウジョウバエ]]では、遺伝子破壊体<ref><pubmed>7834751</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>7546745</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>10433270</pubmed></ref><ref><pubmed>11095753</pubmed></ref>、温度感受性変異体<ref><pubmed>9728921</pubmed></ref>、SNAREモチーフ中に変異を導入した変異体<ref><pubmed>11717347</pubmed></ref>が作製されており、いずれもシナプス伝達が著しく阻害されている。 | |||

== 関連項目 == | == 関連項目 == | ||

* | * SNAP-25 | ||

* SNARE複合体 | |||

* | * エクソサイトーシス | ||

* | * コンプレキシン | ||

* | * シナプス顆粒 | ||

* | * シナプス前終末 | ||

* | * シナプトタグミン | ||

* | * シナプトブレビン | ||

* | * ボツリヌス毒素 | ||

* 膜融合 | |||

* | * 有芯顆粒 | ||

* | |||

* | |||

== 参考文献 == | == 参考文献 == | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

2015年12月22日 (火) 12:54時点における版

西木 禎一

岡山大学 大学院医歯薬学総合研究科 細胞生理学分野

英語名:syntaxin, 英略語:STX

同義語:p35, HPC-1, synaptocanalin

シンタキシンは、細胞内小胞輸送において膜の融合に関わるタンパク質ファミリーおよびそのメンバーである。ヒトでは、少なくとも19種類のアイソフォームが同定されている。シンタキシンファミリーメンバーの大部分が脳にも発現しているが、この項ではニューロンの機能の大きな特徴である神経伝達物質の放出を担うアイソフォーム1について述べる。

シンタキシンとは

シンタキシン1は、シナプス小胞タンパク質シナプトタグミンと結合する分子量約35,000の内在性膜タンパク質p35Aおよびp35Bとしてラット脳可溶化画分から同定された[1]。シンタキシン1のAとBは異なる遺伝子によりコードされているが、どちらも288個のアミノ酸からなり、両者のアミノ酸配列は約80%の相同性をもつ。シナプス小胞のドッキングと開口放出に関わるとの予測から、「順番に整理して一緒に並べること」を意味する古代ギリシャ語σψνταξισ (syntaxis) にちなみ命名された。ほぼ同時期に複数のグループにより同定されたので、HPC-1[2]あるいはsynaptocanalin[3]とも呼ばれる。

シンタキシンファミリーは、SNARE (soluble N-etylmaleimide sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptorの略) と総称される膜融合関連タンパク質スーパーファミリーの一員でもある。SNAREは、輸送小胞に局在するv-SNARE (vはvesicularのv) と標的膜に存在するt-SNARE (tはtarget-membraneのt) の2種類に大別される[4]。シンタキシン1はその局在(後述)からt-SNAREに属するとともに、SNAREモチーフの中央にグルタミン残基を持つことから、そのアミノ酸一文字表記にならいQ-SNAREとも分類される[5]。

構造

シンタキシン1は、4つのドメインがリンカーでつながれた構造をしている(図1)。アミノ末端のNペプチドモチーフ(1-19)は、Munc-18との結合に関わる(後述)[6]。二番目のHabcと呼ばれるドメイン(~27-146)では、3本のαへリックスが逆平行に結合し束になっている[7][8]。Habcに続くリンカーは非常にフレキシブルで[9]、Habcは次のH3ドメインに折り重なることよりSNARE複合体の膜融合能を制御する負の調節ドメインとして働く[10]。

シンタキシン1のカルボキシ末端側3分の1は、膜融合能を発揮するのに必要最小限の領域である。SNAREモチーフを含むH3ドメイン(~185-254)は、SNAP-25ならびにシナプトブレビンと結合し、膜融合能をもつSNARE複合体を形成する[11]。続く膜貫通ドメイン(266-288)は、細胞膜に埋め込まれているが貫通はしない[12]。これら両ドメインを含む組換えフラグメントを全長のSNAP-25ととともに再構成した人工脂質小胞は、シナプトブレビンを再構成した人工脂質小胞と自発的に融合する[13]。

モノメリックなシンタキシン1は、活性化状態と不活性状態を移行する[14]。活性化状態では、HabcとH3が解離したいわゆる開いた構造をとり、SNAP-25およびシナプトブレビンと結合できる。これに対し、HabcがH3に折り重なった閉じた構造になると不活性型となり、SNARE複合体を形成できない[15][16]。

生体内および細胞内分布

シンタキシン1は神経系に特異的に発現する。組織染色において大脳皮質、海馬、小脳、脊髄、網膜のシナプスが豊富な領域に観察される[17]。有郭乳頭味蕾[18]、蝸牛内のコルチ器[19]、松果体細胞[20] にも存在する。神経系だけでなく、発生学的にニューロンと同じ外胚葉由来の副腎髄質にも発現している[21]。中枢神経系および末梢神経系の両方において、1Aと1Bの分布は異なる[22] [23]。

ニューロンにおいてシンタキシン1は、主にシナプス前膜を含む細胞膜内面に局在する一方、シナプス小胞膜にも認められる[24][25][26]。小脳皮質においては、ほとんどのグルタミン酸作動性終末と、一部のGABA作動性シナプスに局在する[27]。その他にも、視索上核のオキシトシンニューロンでは軸索終末だけでなく細胞体や樹状突起に発現が見られるとともに[28]、ヒヨコの毛様体神経節のHeld杯状シナプス前部[29]、カエルの運動神経終末[30]にも存在する。アストロサイトにも発現している[31][32]。

翻訳後修飾

シンタキシン1は、PKCおよびCaMKII[33][34] 、カゼインキナーゼ1および2[35][36][37][38][39]によりリン酸化される。PKAについては議論が分かれている[40][41]。リン酸化以外に、ニトロ化[42]、Sニトロシル化[43]、パルミトイル化[44]を受け、ユビキチン-プロテアソーム経路により分解される[45]。

結合タンパク質

in vitroにおいてシンタキシン1は、約50種類ものタンパク質と結合することが示されている。ここでは、神経伝達物質の放出に関与しているものを中心に取上げる。

SNARE(SNAP-25およびシナプトブレビン)

シンタキシン1は、同じくt-SNAREであるSNAP-25と自身のH3ドメインを介し結合する[46]。会合比により2種類の複合体が存在する。1:1で結合したt-SNAREヘテロニ量体は、v-SNAREであるシナプトブレビン(別名VAMP)と結合しSNARE複合体を形成する。一方、シンタキシン二分子にSNAP-25が一分子結合した2:1複合体(通称)は、シナプトブレビンと結合できない[47]。したがって、シナプス前終末の放出部位では、別の分子により1:1複合体の状態が維持されていると予想される。

シンタキシン1、SNAP-25、およびシナプトブレビンが1:1:1の比で結合したSNARE複合体は、コイルドコイル構造をもつ[48]。よく目にするシナプス小胞膜とシナプス前膜との間で形成されているSNARE複合体の模式図は、シンタキシンのH3ドメインとSNAP-25およびシナプトブレビンの細胞質フラグメントからなる複合体の立体構造解析結果に膜貫通領域などを描き足したものである(図2)。組織を可溶化した後などに溶液中に存在するSNARE複合体は強固に結合しており、強力な界面活性剤に対しても耐性を持ち、SDS存在下でも煮沸しない限り解離しない[49]。

シナプトタグミン

シンタキシン1は、H3ドメインを介して神経伝達物質放出のカルシウムイオンセンサーの最有力候補シナプトタグミン1と結合する[50][51]。カルシウムイオン非存在下では、シナプトタグミンのC2Bドメインと結合する[52][53]。大腸菌で発現させた組換えタンパク質同士の結合は、結合実験に用いるフラグメントの大きさや付加するタグによって、特にカルシウムイオンの要求性に、大きな影響を受ける[54]。ある条件下ではシンタキシン1とシナプトタグミン1の結合はカルシウム依存性であり[55]、シナプトタグミンのC2Aドメインへのカルシウムイオンの結合が必須である[56]。しかし、C2Aのカルシウム結合能を欠失させた変異シナプトタグミンを発現させたニューロンで神経伝達物質の放出に異常が認められないことから[57]、シンタキシンとシナプトグミンのカルシウム依存性結合の伝達物質放出における意義は不明である。

コンプレキシン

シンタキシンは、コンプレキシン(別名シナフィン)とH3を介して結合する[58][59]。コンプレキシンは、SNARE複合体による膜融合を一時停止させる役割を持つとされるシナプス前終末タンパク質である[60]。コンプレキシンの中央部分とSNARE複合体の結合状態の立体構造が明らかにされている[61]。

Munc-18

小胞のドッキングあるいはプライミングに関与するMunc-18(別名n-Sec1)のシンタキシンへの結合は[62][63]、当初SNARE複合体の形成を阻害するとされていた[64]。これは、単純化された結合実験において、シンタキシン1のNペプチドにMunc18が結合している時はその閉構造が安定化し[65]、SNAP-25と結合できないためである[66] 。しかしその後、Munc-18と結合したシンタキシン1でもMunc-13存在下では開構造へと変形し[67]、SNARE複合体を形成できることが明らかにされた(後述)[68][69][70]。このように、Munc-18は、シンタキシン1の開閉構造に応じた二種類の結合様式でモノメリックなシンタキシン1とSNARE複合体中のシンタキシン1の両方に結合することができる。シンタキシン1とMunc-18の結合は、両者のリン酸化[71][72][73][74]や、アラキドン酸[75]およびスフィンゴシン[76]により制御される。シンタキシンとMunc-18の複合体の立体構造も明らかにされている[77] 。

Munc-13

Munc-13は、シンタキシンを閉構造から開構造へ変換することで、Munc18と結合したシンタキシンをSNARE複合体が形成できるようにする[78][79]。このタンパク質間相互作用は、シナプス小胞のドッキングおよびプライミングに関与しているとされている[80][81]。

カルシウムチャネル

シンタキシンは多様なカルシウムチャネルと結合する[82]

[83]

[84]

。中でもN型 カルシウムチャネルとの結合は良く調べられていて[85][86]、チャネルの細胞質内ループ中のシンプリントsynprintと呼ばれる部位とシンタキシンのNペプチドがカルシウムイオン濃度依存性に結合する[87][88][89]。また、これとは別にシンタキシンの膜貫通領域とその直前の細胞質領域が調節に関与している[90]。。Gタンパク質によるカルシウムチャネルの機能調節は、シンタキシンとGβとGγからなるヘテロ二量体との直接結合により促進される[91]。

その他にもシンタキシンは、CAPS、VAP-A、α-fodrin、CaMKII、granuphilin、staring、amisyn、D53、taxillin、各種伝達物質トランスポーター、Death-associated protein (DAP)キナーゼ、ある種のKチャネル、syntabulin、ミオシンVa、クラスC-Vps複合体、オトフェリン、HSP-70、IP3受容体、Mチャネル、DCC (deleted in colorectal cancer)、PRIP (phospholipase C-related but catalytically inactive protein)、CCCrel-1、cysteine-string protein (CSP) 、チューブリン、syncollin、presenilin-1、ダイナミン、α-SNAP、シナプトブレビン、syntaphilin、tomosyn、

あるいはdopamine transporter(DAT)/the receptor for activated C kinases (RACK1) と結合する。

機能

シナプス前膜に存在するシンタキシン1は、エンドサイトーシスを含め[92]シナプス小胞の循環のいくつかの過程に直接または間接的に関わる。その中でもカルシウム依存性の小胞開口放出過程における役割について最も研究が進んでおり、シンタキシン1はシナプス前膜と小胞膜との間でSNAP-25およびシナプトブレビンとSNARE複合体を形成し、両方の膜を限りなく近づけて融合させ神経伝達物質を開口放出させると考えられている[93]。マウスの内耳有毛細胞からの伝達物質放出には関与しないという例外はあるが[94]、実験材料として使われる多くの神経標本および開口放出のモデル細胞における伝達物質放出にはシンタキシン1が必須である[95][96][97][98][99]。

シンタキシン1は、開口放出に先立ちシナプス小胞や有芯小胞を放出部位へドッキングさせる。実際、カエルの神経筋接合部[100]ならびに副腎髄質クロマフィン細胞[101]においてシンタキシンを切断あるいは破壊すると小胞のドッキングが阻害される。一方、ニューロン間のシナプスではシンタキシンの機能を阻害してもドッキングに影響はない[102][103][104]。

刺激に応じた小胞の開口放出はカルシウム依存性だが、シンタキシン1を含むSNAREにはカルシウムイオン結合能はない。しかし、シンタキシン自身は、カルシウムチャネルへの結合を介して小胞を放出部位へドッキングさせる[105]。一方で、カルシウムチャネルの機能を抑制することから[106][107]、伝達物質放出のカルシウムイオンによる制御において相反する二種類の働きを併せ持つ[108]。

それ以外にも、開口放出時に形成されると考えられているフュージョンポアへの関与[109] 、神経突起の伸長[110][111][112]、学習と記憶に関与する可能性[113][114][115][116]が示唆されている。

疾患との関わり

ボツリヌス中毒の主な症状である弛緩性麻痺は、運動神経終末からのアセチルコリンの放出阻害による。これは、中毒の原因であるボツリヌス菌が産生する毒素のもつタンパク質分解酵素活性によるSNAREの切断に起因する。7種類存在するボツリヌス毒素の中、C型毒素はシンタキシ1をカルボキシ末端付近の1箇所、リシン残基とアラニン残基(1Aでは253番目と254番目、1Bでは252番目と253番目)の間で切断する[117][118]。

中枢ならびに末梢神経系疾患との関連性も示唆されている。統合失調症[119][120][121]、高機能自閉症[122]、脳虚血後[123]においてシンタキシン1の発現量が増加していることが報告されている。末梢神経障害による異痛症にシンタキシン1の発現低下が関与している可能性も言われている[124]。

遺伝子操作動物

シンタキシン1Aのノックアウトマウスは生育可能だが、恐怖条件付け記憶の阻害に加え、セロトニン作動性神経系の異常と考えられる行動異常と視床下部-下垂体-副腎系の機能不全を呈す[125][126][127]。 これに対し、シンタキシン1Bのノックアウトマウスは生後2週間までしか生存できず、グルタミン酸あるいはGABAの放出においてシナプス小胞の正常な開口放出と即時放出可能プールの形成が阻害されている[128]。恒常的に開構造をとる変異シンタキシン1B遺伝子を強制発現させたノックインマウスは生育可能だが、2-3ヶ月齢で全身痙攣を呈し死にいたる[129]。ショウジョウバエでは、遺伝子破壊体[130][131][132][133]、温度感受性変異体[134]、SNAREモチーフ中に変異を導入した変異体[135]が作製されており、いずれもシナプス伝達が著しく阻害されている。

関連項目

- SNAP-25

- SNARE複合体

- エクソサイトーシス

- コンプレキシン

- シナプス顆粒

- シナプス前終末

- シナプトタグミン

- シナプトブレビン

- ボツリヌス毒素

- 膜融合

- 有芯顆粒

参考文献

- ↑

Bennett, M.K., Calakos, N., & Scheller, R.H. (1992).

Syntaxin: a synaptic protein implicated in docking of synaptic vesicles at presynaptic active zones. Science (New York, N.Y.), 257(5067), 255-9. [PubMed:1321498] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Inoue, A., Obata, K., & Akagawa, K. (1992).

Cloning and sequence analysis of cDNA for a neuronal cell membrane antigen, HPC-1. The Journal of biological chemistry, 267(15), 10613-9. [PubMed:1587842] [WorldCat] - ↑

Abe, T., Saisu, H., & Horikawa, H.P. (1993).

Synaptocanalins (N-type Ca channel-associated proteins) form a complex with SNAP-25 and synaptotagmin. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 707, 373-5. [PubMed:9137572] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Söllner, T., Whiteheart, S.W., Brunner, M., Erdjument-Bromage, H., Geromanos, S., Tempst, P., & Rothman, J.E. (1993).

SNAP receptors implicated in vesicle targeting and fusion. Nature, 362(6418), 318-24. [PubMed:8455717] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fasshauer, D., Sutton, R.B., Brunger, A.T., & Jahn, R. (1998).

Conserved structural features of the synaptic fusion complex: SNARE proteins reclassified as Q- and R-SNAREs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 95(26), 15781-6. [PubMed:9861047] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Rathore, S.S., Bend, E.G., Yu, H., Hammarlund, M., Jorgensen, E.M., & Shen, J. (2010).

Syntaxin N-terminal peptide motif is an initiation factor for the assembly of the SNARE-Sec1/Munc18 membrane fusion complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 107(52), 22399-406. [PubMed:21139055] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fernandez, I., Ubach, J., Dulubova, I., Zhang, X., Südhof, T.C., & Rizo, J. (1998).

Three-dimensional structure of an evolutionarily conserved N-terminal domain of syntaxin 1A. Cell, 94(6), 841-9. [PubMed:9753330] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Lerman, J.C., Robblee, J., Fairman, R., & Hughson, F.M. (2000).

Structural analysis of the neuronal SNARE protein syntaxin-1A. Biochemistry, 39(29), 8470-9. [PubMed:10913252] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Margittai, M., Fasshauer, D., Jahn, R., & Langen, R. (2003).

The Habc domain and the SNARE core complex are connected by a highly flexible linker. Biochemistry, 42(14), 4009-14. [PubMed:12680753] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Parlati, F., Weber, T., McNew, J.A., Westermann, B., Söllner, T.H., & Rothman, J.E. (1999).

Rapid and efficient fusion of phospholipid vesicles by the alpha-helical core of a SNARE complex in the absence of an N-terminal regulatory domain. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 96(22), 12565-70. [PubMed:10535962] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Zhong, P., Chen, Y.A., Tam, D., Chung, D., Scheller, R.H., & Miljanich, G.P. (1997).

An alpha-helical minimal binding domain within the H3 domain of syntaxin is required for SNAP-25 binding. Biochemistry, 36(14), 4317-26. [PubMed:9100028] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Suga, K., Yamamori, T., & Akagawa, K. (2003).

Identification of the carboxyl-terminal membrane-anchoring region of HPC-1/syntaxin 1A with the substituted-cysteine-accessibility method and monoclonal antibodies. Journal of biochemistry, 133(3), 325-34. [PubMed:12761168] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Weber, T., Zemelman, B.V., McNew, J.A., Westermann, B., Gmachl, M., Parlati, F., ..., & Rothman, J.E. (1998).

SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell, 92(6), 759-72. [PubMed:9529252] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Margittai, M., Widengren, J., Schweinberger, E., Schröder, G.F., Felekyan, S., Haustein, E., ..., & Seidel, C.A. (2003).

Single-molecule fluorescence resonance energy transfer reveals a dynamic equilibrium between closed and open conformations of syntaxin 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(26), 15516-21. [PubMed:14668446] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Chen, X., Lu, J., Dulubova, I., & Rizo, J. (2008).

NMR analysis of the closed conformation of syntaxin-1. Journal of biomolecular NMR, 41(1), 43-54. [PubMed:18458823] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Dulubova, I., Sugita, S., Hill, S., Hosaka, M., Fernandez, I., Südhof, T.C., & Rizo, J. (1999).

A conformational switch in syntaxin during exocytosis: role of munc18. The EMBO journal, 18(16), 4372-82. [PubMed:10449403] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Inoue, A., & Akagawa, K. (1993).

Neuron specific expression of a membrane protein, HPC-1: tissue distribution, and cellular and subcellular localization of immunoreactivity and mRNA. Brain research. Molecular brain research, 19(1-2), 121-8. [PubMed:8361334] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Yang, R., Ma, H., Thomas, S.M., & Kinnamon, J.C. (2007).

Immunocytochemical analysis of syntaxin-1 in rat circumvallate taste buds. The Journal of comparative neurology, 502(6), 883-93. [PubMed:17447252] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Safieddine, S., & Wenthold, R.J. (1999).

SNARE complex at the ribbon synapses of cochlear hair cells: analysis of synaptic vesicle- and synaptic membrane-associated proteins. The European journal of neuroscience, 11(3), 803-12. [PubMed:10103074] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Redecker, P. (1996).

Synaptotagmin I, synaptobrevin II, and syntaxin I are coexpressed in rat and gerbil pinealocytes. Cell and tissue research, 283(3), 443-54. [PubMed:8593674] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Gutierrez, L.M., Quintanar, J.L., Viniegra, S., Salinas, E., Moya, F., & Reig, J.A. (1995).

Anti-syntaxin antibodies inhibit calcium-dependent catecholamine secretion from permeabilized chromaffin cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 206(1), 1-7. [PubMed:7818508] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Aguado, F., Majó, G., Ruiz-Montasell, B., Llorens, J., Marsal, J., & Blasi, J. (1999).

Syntaxin 1A and 1B display distinct distribution patterns in the rat peripheral nervous system. Neuroscience, 88(2), 437-46. [PubMed:10197765] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ruiz-Montasell, B., Aguado, F., Majó, G., Chapman, E.R., Canals, J.M., Marsal, J., & Blasi, J. (1996).

Differential distribution of syntaxin isoforms 1A and 1B in the rat central nervous system. The European journal of neuroscience, 8(12), 2544-52. [PubMed:8996803] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Koh, S., Yamamoto, A., Inoue, A., Inoue, Y., Akagawa, K., Kawamura, Y., ..., & Tashiro, Y. (1993).

Immunoelectron microscopic localization of the HPC-1 antigen in rat cerebellum. Journal of neurocytology, 22(11), 995-1005. [PubMed:8301329] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Garcia, E.P., McPherson, P.S., Chilcote, T.J., Takei, K., & De Camilli, P. (1995).

rbSec1A and B colocalize with syntaxin 1 and SNAP-25 throughout the axon, but are not in a stable complex with syntaxin. The Journal of cell biology, 129(1), 105-20. [PubMed:7698978] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Pertsinidis, A., Mukherjee, K., Sharma, M., Pang, Z.P., Park, S.R., Zhang, Y., ..., & Chu, S. (2013).

Ultrahigh-resolution imaging reveals formation of neuronal SNARE/Munc18 complexes in situ. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(30), E2812-20. [PubMed:23821748] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Benagiano, V., Lorusso, L., Flace, P., Girolamo, F., Rizzi, A., Bosco, L., ..., & Ambrosi, G. (2011).

VAMP-2, SNAP-25A/B and syntaxin-1 in glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses of the rat cerebellar cortex. BMC neuroscience, 12, 118. [PubMed:22094010] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tobin, V., Schwab, Y., Lelos, N., Onaka, T., Pittman, Q.J., & Ludwig, M. (2012).

Expression of exocytosis proteins in rat supraoptic nucleus neurones. Journal of neuroendocrinology, 24(4), 629-41. [PubMed:21988098] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Li, Q., Lau, A., Morris, T.J., Guo, L., Fordyce, C.B., & Stanley, E.F. (2004).

A syntaxin 1, Galpha(o), and N-type calcium channel complex at a presynaptic nerve terminal: analysis by quantitative immunocolocalization. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 24(16), 4070-81. [PubMed:15102922] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Boudier, J.A., Charvin, N., Boudier, J.L., Fathallah, M., Tagaya, M., Takahashi, M., & Seagar, M.J. (1996).

Distribution of components of the SNARE complex in relation to transmitter release sites at the frog neuromuscular junction. The European journal of neuroscience, 8(3), 545-52. [PubMed:8963446] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Jeftinija, S.D., Jeftinija, K.V., & Stefanovic, G. (1997).

Cultured astrocytes express proteins involved in vesicular glutamate release. Brain research, 750(1-2), 41-7. [PubMed:9098527] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Schubert, V., Bouvier, D., & Volterra, A. (2011).

SNARE protein expression in synaptic terminals and astrocytes in the adult hippocampus: a comparative analysis. Glia, 59(10), 1472-88. [PubMed:21656854] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hirling, H., & Scheller, R.H. (1996).

Phosphorylation of synaptic vesicle proteins: modulation of the alpha SNAP interaction with the core complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(21), 11945-9. [PubMed:8876242] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Risinger, C., & Bennett, M.K. (1999).

Differential phosphorylation of syntaxin and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) isoforms. Journal of neurochemistry, 72(2), 614-24. [PubMed:9930733] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Dubois, T., Kerai, P., Learmonth, M., Cronshaw, A., & Aitken, A. (2002).

Identification of syntaxin-1A sites of phosphorylation by casein kinase I and casein kinase II. European journal of biochemistry, 269(3), 909-14. [PubMed:11846792] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Bennett, M.K., Calakos, N., & Scheller, R.H. (1992).

Syntaxin: a synaptic protein implicated in docking of synaptic vesicles at presynaptic active zones. Science (New York, N.Y.), 257(5067), 255-9. [PubMed:1321498] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Risinger, C., & Bennett, M.K. (1999).

Differential phosphorylation of syntaxin and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) isoforms. Journal of neurochemistry, 72(2), 614-24. [PubMed:9930733] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Foletti, D.L., Lin, R., Finley, M.A., & Scheller, R.H. (2000).

Phosphorylated syntaxin 1 is localized to discrete domains along a subset of axons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 20(12), 4535-44. [PubMed:10844023] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

DeGiorgis, J.A., Jaffe, H., Moreira, J.E., Carlotti, C.G., Leite, J.P., Pant, H.C., & Dosemeci, A. (2005).

Phosphoproteomic analysis of synaptosomes from human cerebral cortex. Journal of proteome research, 4(2), 306-15. [PubMed:15822905] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hirling, H., & Scheller, R.H. (1996).

Phosphorylation of synaptic vesicle proteins: modulation of the alpha SNAP interaction with the core complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 93(21), 11945-9. [PubMed:8876242] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Risinger, C., & Bennett, M.K. (1999).

Differential phosphorylation of syntaxin and synaptosome-associated protein of 25 kDa (SNAP-25) isoforms. Journal of neurochemistry, 72(2), 614-24. [PubMed:9930733] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Prior, I.A., & Clague, M.J. (2000).

Detection of thiol modification following generation of reactive nitrogen species: analysis of synaptic vesicle proteins. Biochimica et biophysica acta, 1475(3), 281-6. [PubMed:10913827] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Palmer, Z.J., Duncan, R.R., Johnson, J.R., Lian, L.Y., Mello, L.V., Booth, D., ..., & Morgan, A. (2008).

S-nitrosylation of syntaxin 1 at Cys(145) is a regulatory switch controlling Munc18-1 binding. The Biochemical journal, 413(3), 479-91. [PubMed:18452404] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Prescott, G.R., Gorleku, O.A., Greaves, J., & Chamberlain, L.H. (2009).

Palmitoylation of the synaptic vesicle fusion machinery. Journal of neurochemistry, 110(4), 1135-49. [PubMed:19508429] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Chin, L.S., Vavalle, J.P., & Li, L. (2002).

Staring, a novel E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase that targets syntaxin 1 for degradation. The Journal of biological chemistry, 277(38), 35071-9. [PubMed:12121982] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Zhong, P., Chen, Y.A., Tam, D., Chung, D., Scheller, R.H., & Miljanich, G.P. (1997).

An alpha-helical minimal binding domain within the H3 domain of syntaxin is required for SNAP-25 binding. Biochemistry, 36(14), 4317-26. [PubMed:9100028] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fasshauer, D., Otto, H., Eliason, W.K., Jahn, R., & Brünger, A.T. (1997).

Structural changes are associated with soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive fusion protein attachment protein receptor complex formation. The Journal of biological chemistry, 272(44), 28036-41. [PubMed:9346956] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Sutton, R.B., Fasshauer, D., Jahn, R., & Brunger, A.T. (1998).

Crystal structure of a SNARE complex involved in synaptic exocytosis at 2.4 A resolution. Nature, 395(6700), 347-53. [PubMed:9759724] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hayashi, T., McMahon, H., Yamasaki, S., Binz, T., Hata, Y., Südhof, T.C., & Niemann, H. (1994).

Synaptic vesicle membrane fusion complex: action of clostridial neurotoxins on assembly. The EMBO journal, 13(21), 5051-61. [PubMed:7957071] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Chapman, E.R. (2008).

How does synaptotagmin trigger neurotransmitter release? Annual review of biochemistry, 77, 615-41. [PubMed:18275379] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Südhof, T.C. (2012).

Calcium control of neurotransmitter release. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in biology, 4(1), a011353. [PubMed:22068972] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Rickman, C., & Davletov, B. (2003).

Mechanism of calcium-independent synaptotagmin binding to target SNAREs. The Journal of biological chemistry, 278(8), 5501-4. [PubMed:12496268] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Masumoto, T., Suzuki, K., Ohmori, I., Michiue, H., Tomizawa, K., Fujimura, A., ..., & Matsui, H. (2012).

Ca(2+)-independent syntaxin binding to the C(2)B effector region of synaptotagmin. Molecular and cellular neurosciences, 49(1), 1-8. [PubMed:22008253] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Kee, Y., & Scheller, R.H. (1996).

Localization of synaptotagmin-binding domains on syntaxin. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 16(6), 1975-81. [PubMed:8604041] [WorldCat] - ↑

Li, C., Ullrich, B., Zhang, J.Z., Anderson, R.G., Brose, N., & Südhof, T.C. (1995).

Ca(2+)-dependent and -independent activities of neural and non-neural synaptotagmins. Nature, 375(6532), 594-9. [PubMed:7791877] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Shao, X., Li, C., Fernandez, I., Zhang, X., Südhof, T.C., & Rizo, J. (1997).

Synaptotagmin-syntaxin interaction: the C2 domain as a Ca2+-dependent electrostatic switch. Neuron, 18(1), 133-42. [PubMed:9010211] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Robinson, I.M., Ranjan, R., & Schwarz, T.L. (2002).

Synaptotagmins I and IV promote transmitter release independently of Ca(2+) binding in the C(2)A domain. Nature, 418(6895), 336-40. [PubMed:12110845] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

McMahon, H.T., Missler, M., Li, C., & Südhof, T.C. (1995).

Complexins: cytosolic proteins that regulate SNAP receptor function. Cell, 83(1), 111-9. [PubMed:7553862] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ishizuka, T., Saisu, H., Suzuki, T., Kirino, Y., & Abe, T. (1997).

Molecular cloning of synaphins/complexins, cytosolic proteins involved in transmitter release, in the electric organ of an electric ray (Narke japonica). Neuroscience letters, 232(2), 107-10. [PubMed:9302098] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Südhof, T.C., & Rothman, J.E. (2009).

Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science (New York, N.Y.), 323(5913), 474-7. [PubMed:19164740] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Chen, X., Tomchick, D.R., Kovrigin, E., Araç, D., Machius, M., Südhof, T.C., & Rizo, J. (2002).

Three-dimensional structure of the complexin/SNARE complex. Neuron, 33(3), 397-409. [PubMed:11832227] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hata, Y., Slaughter, C.A., & Südhof, T.C. (1993).

Synaptic vesicle fusion complex contains unc-18 homologue bound to syntaxin. Nature, 366(6453), 347-51. [PubMed:8247129] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Pevsner, J., Hsu, S.C., & Scheller, R.H. (1994).

n-Sec1: a neural-specific syntaxin-binding protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 91(4), 1445-9. [PubMed:8108429] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Pevsner, J., Hsu, S.C., & Scheller, R.H. (1994).

n-Sec1: a neural-specific syntaxin-binding protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 91(4), 1445-9. [PubMed:8108429] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Dawidowski, D., & Cafiso, D.S. (2013).

Allosteric control of syntaxin 1a by Munc18-1: characterization of the open and closed conformations of syntaxin. Biophysical journal, 104(7), 1585-94. [PubMed:23561535] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Burkhardt, P., Hattendorf, D.A., Weis, W.I., & Fasshauer, D. (2008).

Munc18a controls SNARE assembly through its interaction with the syntaxin N-peptide. The EMBO journal, 27(7), 923-33. [PubMed:18337752] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Sassa, T., Harada, S., Ogawa, H., Rand, J.B., Maruyama, I.N., & Hosono, R. (1999).

Regulation of the UNC-18-Caenorhabditis elegans syntaxin complex by UNC-13. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 19(12), 4772-7. [PubMed:10366611] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Zilly, F.E., Sørensen, J.B., Jahn, R., & Lang, T. (2006).

Munc18-bound syntaxin readily forms SNARE complexes with synaptobrevin in native plasma membranes. PLoS biology, 4(10), e330. [PubMed:17002520] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Dulubova, I., Khvotchev, M., Liu, S., Huryeva, I., Südhof, T.C., & Rizo, J. (2007).

Munc18-1 binds directly to the neuronal SNARE complex. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(8), 2697-702. [PubMed:17301226] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Rickman, C., Medine, C.N., Bergmann, A., & Duncan, R.R. (2007).

Functionally and spatially distinct modes of munc18-syntaxin 1 interaction. The Journal of biological chemistry, 282(16), 12097-103. [PubMed:17264080] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fujita, Y., Sasaki, T., Fukui, K., Kotani, H., Kimura, T., Hata, Y., ..., & Takai, Y. (1996).

Phosphorylation of Munc-18/n-Sec1/rbSec1 by protein kinase C: its implication in regulating the interaction of Munc-18/n-Sec1/rbSec1 with syntaxin. The Journal of biological chemistry, 271(13), 7265-8. [PubMed:8631738] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Shuang, R., Zhang, L., Fletcher, A., Groblewski, G.E., Pevsner, J., & Stuenkel, E.L. (1998).

Regulation of Munc-18/syntaxin 1A interaction by cyclin-dependent kinase 5 in nerve endings. The Journal of biological chemistry, 273(9), 4957-66. [PubMed:9478941] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Tian, J.H., Das, S., & Sheng, Z.H. (2003).

Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of syntaxin-1A by the death-associated protein (DAP) kinase regulates its interaction with Munc18. The Journal of biological chemistry, 278(28), 26265-74. [PubMed:12730201] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Rickman, C., & Duncan, R.R. (2010).

Munc18/Syntaxin interaction kinetics control secretory vesicle dynamics. The Journal of biological chemistry, 285(6), 3965-72. [PubMed:19748891] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Connell, E., Darios, F., Broersen, K., Gatsby, N., Peak-Chew, S.Y., Rickman, C., & Davletov, B. (2007).

Mechanism of arachidonic acid action on syntaxin-Munc18. EMBO reports, 8(4), 414-9. [PubMed:17363971] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Camoletto, P.G., Vara, H., Morando, L., Connell, E., Marletto, F.P., Giustetto, M., ..., & Ledesma, M.D. (2009).

Synaptic vesicle docking: sphingosine regulates syntaxin1 interaction with Munc18. PloS one, 4(4), e5310. [PubMed:19390577] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Misura, K.M., Scheller, R.H., & Weis, W.I. (2000).

Three-dimensional structure of the neuronal-Sec1-syntaxin 1a complex. Nature, 404(6776), 355-62. [PubMed:10746715] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hammarlund, M., Palfreyman, M.T., Watanabe, S., Olsen, S., & Jorgensen, E.M. (2007).

Open syntaxin docks synaptic vesicles. PLoS biology, 5(8), e198. [PubMed:17645391] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ma, C., Li, W., Xu, Y., & Rizo, J. (2011).

Munc13 mediates the transition from the closed syntaxin-Munc18 complex to the SNARE complex. Nature structural & molecular biology, 18(5), 542-9. [PubMed:21499244] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hammarlund, M., Watanabe, S., Schuske, K., & Jorgensen, E.M. (2008).

CAPS and syntaxin dock dense core vesicles to the plasma membrane in neurons. The Journal of cell biology, 180(3), 483-91. [PubMed:18250196] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Richmond, J.E., Weimer, R.M., & Jorgensen, E.M. (2001).

An open form of syntaxin bypasses the requirement for UNC-13 in vesicle priming. Nature, 412(6844), 338-41. [PubMed:11460165] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Seagar, M., Lévêque, C., Charvin, N., Marquèze, B., Martin-Moutot, N., Boudier, J.A., ..., & Takahashi, M. (1999).

Interactions between proteins implicated in exocytosis and voltage-gated calcium channels. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 354(1381), 289-97. [PubMed:10212477] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Catterall, W.A. (1999).

Interactions of presynaptic Ca2+ channels and snare proteins in neurotransmitter release. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 868, 144-59. [PubMed:10414292] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Zamponi, G.W. (2003).

Regulation of presynaptic calcium channels by synaptic proteins. Journal of pharmacological sciences, 92(2), 79-83. [PubMed:12832834] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Lévêque, C., el Far, O., Martin-Moutot, N., Sato, K., Kato, R., Takahashi, M., & Seagar, M.J. (1994).

Purification of the N-type calcium channel associated with syntaxin and synaptotagmin. A complex implicated in synaptic vesicle exocytosis. The Journal of biological chemistry, 269(9), 6306-12. [PubMed:8119979] [WorldCat] - ↑

Yoshida, A., Oho, C., Omori, A., Kuwahara, R., Ito, T., & Takahashi, M. (1992).

HPC-1 is associated with synaptotagmin and omega-conotoxin receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry, 267(35), 24925-8. [PubMed:1334074] [WorldCat] - ↑

Sheng, Z.H., Rettig, J., Takahashi, M., & Catterall, W.A. (1994).

Identification of a syntaxin-binding site on N-type calcium channels. Neuron, 13(6), 1303-13. [PubMed:7993624] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Jarvis, S.E., Barr, W., Feng, Z.P., Hamid, J., & Zamponi, G.W. (2002).

Molecular determinants of syntaxin 1 modulation of N-type calcium channels. The Journal of biological chemistry, 277(46), 44399-407. [PubMed:12221094] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Sheng, Z.H., Rettig, J., Cook, T., & Catterall, W.A. (1996).

Calcium-dependent interaction of N-type calcium channels with the synaptic core complex. Nature, 379(6564), 451-4. [PubMed:8559250] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Bezprozvanny, I., Zhong, P., Scheller, R.H., & Tsien, R.W. (2000).

Molecular determinants of the functional interaction between syntaxin and N-type Ca2+ channel gating. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 97(25), 13943-8. [PubMed:11087812] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Jarvis, S.E., Magga, J.M., Beedle, A.M., Braun, J.E., & Zamponi, G.W. (2000).

G protein modulation of N-type calcium channels is facilitated by physical interactions between syntaxin 1A and Gbetagamma. The Journal of biological chemistry, 275(9), 6388-94. [PubMed:10692440] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Xu, J., Luo, F., Zhang, Z., Xue, L., Wu, X.S., Chiang, H.C., ..., & Wu, L.G. (2013).

SNARE proteins synaptobrevin, SNAP-25, and syntaxin are involved in rapid and slow endocytosis at synapses. Cell reports, 3(5), 1414-21. [PubMed:23643538] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Chen, Y.A., Scales, S.J., Patel, S.M., Doung, Y.C., & Scheller, R.H. (1999).

SNARE complex formation is triggered by Ca2+ and drives membrane fusion. Cell, 97(2), 165-74. [PubMed:10219238] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Nouvian, R., Neef, J., Bulankina, A.V., Reisinger, E., Pangršič, T., Frank, T., ..., & Moser, T. (2011).

Exocytosis at the hair cell ribbon synapse apparently operates without neuronal SNARE proteins. Nature neuroscience, 14(4), 411-3. [PubMed:21378973] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Gutierrez, L.M., Quintanar, J.L., Viniegra, S., Salinas, E., Moya, F., & Reig, J.A. (1995).

Anti-syntaxin antibodies inhibit calcium-dependent catecholamine secretion from permeabilized chromaffin cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 206(1), 1-7. [PubMed:7818508] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Mochida, S., Saisu, H., Kobayashi, H., & Abe, T. (1995).

Impairment of syntaxin by botulinum neurotoxin C1 or antibodies inhibits acetylcholine release but not Ca2+ channel activity. Neuroscience, 65(3), 905-15. [PubMed:7609887] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Sugimori, M., Tong, C.K., Fukuda, M., Moreira, J.E., Kojima, T., Mikoshiba, K., & Llinás, R. (1998).

Presynaptic injection of syntaxin-specific antibodies blocks transmission in the squid giant synapse. Neuroscience, 86(1), 39-51. [PubMed:9692742] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Kushima, Y., Fujiwara, T., Morimoto, T., & Akagawa, K. (1995).

Involvement of HPC-1/syntaxin-1A antigen in transmitter release from PC12h cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 212(1), 97-103. [PubMed:7612024] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

O'Connor, V., Heuss, C., De Bello, W.M., Dresbach, T., Charlton, M.P., Hunt, J.H., ..., & Schäfer, T. (1997).

Disruption of syntaxin-mediated protein interactions blocks neurotransmitter secretion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 94(22), 12186-91. [PubMed:9342384] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Stanley, E.F., Reese, T.S., & Wang, G.Z. (2003).

Molecular scaffold reorganization at the transmitter release site with vesicle exocytosis or botulinum toxin C1. The European journal of neuroscience, 18(8), 2403-7. [PubMed:14622203] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

de Wit, H., Cornelisse, L.N., Toonen, R.F., & Verhage, M. (2006).

Docking of secretory vesicles is syntaxin dependent. PloS one, 1, e126. [PubMed:17205130] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Stanley, E.F., Reese, T.S., & Wang, G.Z. (2003).

Molecular scaffold reorganization at the transmitter release site with vesicle exocytosis or botulinum toxin C1. The European journal of neuroscience, 18(8), 2403-7. [PubMed:14622203] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

de Wit, H., Cornelisse, L.N., Toonen, R.F., & Verhage, M. (2006).

Docking of secretory vesicles is syntaxin dependent. PloS one, 1, e126. [PubMed:17205130] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

O'Connor, V., Heuss, C., De Bello, W.M., Dresbach, T., Charlton, M.P., Hunt, J.H., ..., & Schäfer, T. (1997).

Disruption of syntaxin-mediated protein interactions blocks neurotransmitter secretion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 94(22), 12186-91. [PubMed:9342384] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Cohen, R., Marom, M., & Atlas, D. (2007).

Depolarization-evoked secretion requires two vicinal transmembrane cysteines of syntaxin 1A. PloS one, 2(12), e1273. [PubMed:18060067] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Bezprozvanny, I., Scheller, R.H., & Tsien, R.W. (1995).

Functional impact of syntaxin on gating of N-type and Q-type calcium channels. Nature, 378(6557), 623-6. [PubMed:8524397] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Sutton, K.G., McRory, J.E., Guthrie, H., Murphy, T.H., & Snutch, T.P. (1999).

P/Q-type calcium channels mediate the activity-dependent feedback of syntaxin-1A. Nature, 401(6755), 800-4. [PubMed:10548106] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Keith, R.K., Poage, R.E., Yokoyama, C.T., Catterall, W.A., & Meriney, S.D. (2007).

Bidirectional modulation of transmitter release by calcium channel/syntaxin interactions in vivo. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 27(2), 265-9. [PubMed:17215385] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Han, X., Wang, C.T., Bai, J., Chapman, E.R., & Jackson, M.B. (2004).

Transmembrane segments of syntaxin line the fusion pore of Ca2+-triggered exocytosis. Science (New York, N.Y.), 304(5668), 289-92. [PubMed:15016962] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Igarashi, M., Kozaki, S., Terakawa, S., Kawano, S., Ide, C., & Komiya, Y. (1996).

Growth cone collapse and inhibition of neurite growth by Botulinum neurotoxin C1: a t-SNARE is involved in axonal growth. The Journal of cell biology, 134(1), 205-15. [PubMed:8698815] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Zhou, Q., Xiao, J., & Liu, Y. (2000).

Participation of syntaxin 1A in membrane trafficking involving neurite elongation and membrane expansion. Journal of neuroscience research, 61(3), 321-8. [PubMed:10900079] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Kabayama, H., Takeuchi, M., Taniguchi, M., Tokushige, N., Kozaki, S., Mizutani, A., ..., & Mikoshiba, K. (2011).

Syntaxin 1B suppresses macropinocytosis and semaphorin 3A-induced growth cone collapse. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 31(20), 7357-64. [PubMed:21593320] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Davis, S., Rodger, J., Hicks, A., Mallet, J., & Laroche, S. (1996).

Brain structure and task-specific increase in expression of the gene encoding syntaxin 1B during learning in the rat: a potential molecular marker for learning-induced synaptic plasticity in neural networks. The European journal of neuroscience, 8(10), 2068-74. [PubMed:8921297] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hicks, A., Davis, S., Rodger, J., Helme-Guizon, A., Laroche, S., & Mallet, J. (1997).

Synapsin I and syntaxin 1B: key elements in the control of neurotransmitter release are regulated by neuronal activation and long-term potentiation in vivo. Neuroscience, 79(2), 329-40. [PubMed:9200718] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Helme-Guizon, A., Davis, S., Israel, M., Lesbats, B., Mallet, J., Laroche, S., & Hicks, A. (1998).

Increase in syntaxin 1B and glutamate release in mossy fibre terminals following induction of LTP in the dentate gyrus: a candidate molecular mechanism underlying transsynaptic plasticity. The European journal of neuroscience, 10(7), 2231-7. [PubMed:9749751] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Guo, C.H., Senzel, A., Li, K., & Feng, Z.P. (2010).

De novo protein synthesis of syntaxin-1 and dynamin-1 in long-term memory formation requires CREB1 gene transcription in Lymnaea stagnalis. Behavior genetics, 40(5), 680-93. [PubMed:20563839] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Blasi, J., Chapman, E.R., Yamasaki, S., Binz, T., Niemann, H., & Jahn, R. (1993).

Botulinum neurotoxin C1 blocks neurotransmitter release by means of cleaving HPC-1/syntaxin. The EMBO journal, 12(12), 4821-8. [PubMed:7901002] [PMC] [WorldCat] - ↑

Schiavo, G., Shone, C.C., Bennett, M.K., Scheller, R.H., & Montecucco, C. (1995).

Botulinum neurotoxin type C cleaves a single Lys-Ala bond within the carboxyl-terminal region of syntaxins. The Journal of biological chemistry, 270(18), 10566-70. [PubMed:7737992] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Wong, A.H., Trakalo, J., Likhodi, O., Yusuf, M., Macedo, A., Azevedo, M.H., ..., & Kennedy, J.L. (2004).

Association between schizophrenia and the syntaxin 1A gene. Biological psychiatry, 56(1), 24-9. [PubMed:15219469] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Castillo, M.A., Ghose, S., Tamminga, C.A., & Ulery-Reynolds, P.G. (2010).

Deficits in syntaxin 1 phosphorylation in schizophrenia prefrontal cortex. Biological psychiatry, 67(3), 208-16. [PubMed:19748077] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Gil-Pisa, I., Munarriz-Cuezva, E., Ramos-Miguel, A., Urigüen, L., Meana, J.J., & García-Sevilla, J.A. (2012).

Regulation of munc18-1 and syntaxin-1A interactive partners in schizophrenia prefrontal cortex: down-regulation of munc18-1a isoform and 75 kDa SNARE complex after antipsychotic treatment. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 15(5), 573-88. [PubMed:21669024] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Nakamura, K., Anitha, A., Yamada, K., Tsujii, M., Iwayama, Y., Hattori, E., ..., & Mori, N. (2008).

Genetic and expression analyses reveal elevated expression of syntaxin 1A ( STX1A) in high functioning autism. The international journal of neuropsychopharmacology, 11(8), 1073-84. [PubMed:18593506] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Cao, F., Hata, R., Zhu, P., Niinobe, M., & Sakanaka, M. (2009).

Up-regulation of syntaxin1 in ischemic cortex after permanent focal ischemia in rats. Brain research, 1272, 52-61. [PubMed:19344701] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fukushima, T., Takasusuki, T., Tomitori, H., & Hori, Y. (2011).

Possible involvement of syntaxin 1A downregulation in the late phase of allodynia induced by peripheral nerve injury. Neuroscience, 175, 344-57. [PubMed:21129445] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fujiwara, T., Mishima, T., Kofuji, T., Chiba, T., Tanaka, K., Yamamoto, A., & Akagawa, K. (2006).

Analysis of knock-out mice to determine the role of HPC-1/syntaxin 1A in expressing synaptic plasticity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 26(21), 5767-76. [PubMed:16723534] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fujiwara, T., Snada, M., Kofuji, T., Yoshikawa, T., & Akagawa, K. (2010).

HPC-1/syntaxin 1A gene knockout mice show abnormal behavior possibly related to a disruption in 5-HTergic systems. The European journal of neuroscience, 32(1), 99-107. [PubMed:20576034] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fujiwara, T., Kofuji, T., & Akagawa, K. (2011).

Dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in STX1A knockout mice. Journal of neuroendocrinology, 23(12), 1222-30. [PubMed:21910766] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Mishima, T., Fujiwara, T., Sanada, M., Kofuji, T., Kanai-Azuma, M., & Akagawa, K. (2014).

Syntaxin 1B, but not syntaxin 1A, is necessary for the regulation of synaptic vesicle exocytosis and of the readily releasable pool at central synapses. PloS one, 9(2), e90004. [PubMed:24587181] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Gerber, S.H., Rah, J.C., Min, S.W., Liu, X., de Wit, H., Dulubova, I., ..., & Südhof, T.C. (2008).

Conformational switch of syntaxin-1 controls synaptic vesicle fusion. Science (New York, N.Y.), 321(5895), 1507-10. [PubMed:18703708] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Schulze, K.L., Broadie, K., Perin, M.S., & Bellen, H.J. (1995).

Genetic and electrophysiological studies of Drosophila syntaxin-1A demonstrate its role in nonneuronal secretion and neurotransmission. Cell, 80(2), 311-20. [PubMed:7834751] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Broadie, K., Prokop, A., Bellen, H.J., O'Kane, C.J., Schulze, K.L., & Sweeney, S.T. (1995).

Syntaxin and synaptobrevin function downstream of vesicle docking in Drosophila. Neuron, 15(3), 663-73. [PubMed:7546745] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Wu, M.N., Fergestad, T., Lloyd, T.E., He, Y., Broadie, K., & Bellen, H.J. (1999).

Syntaxin 1A interacts with multiple exocytic proteins to regulate neurotransmitter release in vivo. Neuron, 23(3), 593-605. [PubMed:10433270] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Stewart, B.A., Mohtashami, M., Trimble, W.S., & Boulianne, G.L. (2000).

SNARE proteins contribute to calcium cooperativity of synaptic transmission. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 97(25), 13955-60. [PubMed:11095753] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Littleton, J.T., Chapman, E.R., Kreber, R., Garment, M.B., Carlson, S.D., & Ganetzky, B. (1998).

Temperature-sensitive paralytic mutations demonstrate that synaptic exocytosis requires SNARE complex assembly and disassembly. Neuron, 21(2), 401-13. [PubMed:9728921] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Fergestad, T., Wu, M.N., Schulze, K.L., Lloyd, T.E., Bellen, H.J., & Broadie, K. (2001).

Targeted mutations in the syntaxin H3 domain specifically disrupt SNARE complex function in synaptic transmission. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 21(23), 9142-50. [PubMed:11717347] [PMC] [WorldCat]