ニューレキシン

渡辺 拓也、二井 健介

マサチューセッツ州立大学 メディカルスクール

DOI:10.14931/bsd.3927 原稿受付日:2013年6月4日 原稿完成日:2013年7月29日

担当編集委員:林 康紀(独立行政法人理化学研究所)

英語名:neurexin 英略称:Nrxn

ニューレキシンはシナプス前末端に存在する1回膜貫通型タンパク質であり、シナプス後部の膜タンパク質であるニューロリギン(Neuroligin: ニューロリギン)とシナプス間隙で結合し、シナプス構築や神経伝達物質の放出機構などに関わっている[1][2]。多くのスプライス変異体が存在し、グルタミン酸作動性・GABA作動性神経シナプスの構築の選別に影響すると考えられている[3] [4]。また、自閉症や統合失調症の発症に関与していると考えられている[5] [6] [7] [8] [9] 。

歴史

ニューレキシンが最初にクロゴケグモの毒成分であるα-ラトロトキシンの受容体として発見され、その後、他のニューレキシンが同定された[10]。

矢印:選択的スプライシング部位 SP:シグナルペプチド、LNS: laminin, neurexin, sex-hormone binding protein domain、EGF: 上皮成長因子様ドメイン、CHO: 糖鎖結合部位、TM:膜貫通領域、PDZ-BD: PDZドメイン結合部位

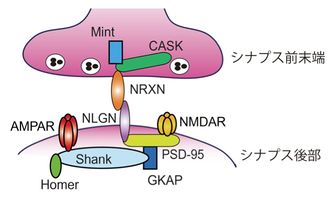

ニューレキシンとニューロリギンはシナプス前末端とシナプス後部間で結合している。ニューレキシンとニューロリギンはそれぞれシナプス前末端とシナプス後部のシナプス局在分子と直接・間接的に結合している。

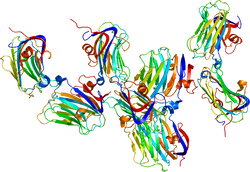

| 動画. βニューレキシンとニューロリギン複合体の3次元構造 2分子のニューレキシンと2分子のニューロリギンがカルシウム依存的に相互作用する。 |

| Neurexin 2 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||

| Symbols | NRXN2; FLJ40892; KIAA0921 | ||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 600566 MGI: 1096362 HomoloGene: 86984 GeneCards: NRXN2 Gene | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

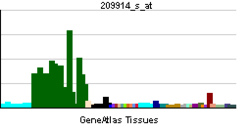

| RNA expression pattern | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| More reference expression data | |||||||||||||

| Orthologs | |||||||||||||

| Species | Human | Mouse | |||||||||||

| Entrez | 9379 | 18190 | |||||||||||

| Ensembl | ENSG00000110076 | ENSMUSG00000033768 | |||||||||||

| UniProt | P58401 | E9PUM9 | |||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | NM_015080 | NM_001205234 | |||||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | NP_055895 | NP_001192163 | |||||||||||

| Location (UCSC) |

Chr 11: 64.37 – 64.49 Mb |

Chr 19: 6.42 – 6.54 Mb | |||||||||||

| PubMed search | [3] | [4] | |||||||||||

| Neurexin 3 | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||

| Symbols | NRXN3; C14orf60 | ||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 600567 MGI: 1096389 HomoloGene: 88711 GeneCards: NRXN3 Gene | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

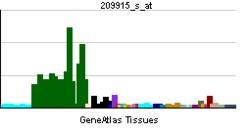

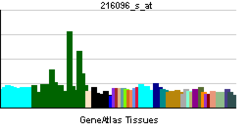

| RNA expression pattern | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| More reference expression data | |||||||||||||

| Orthologs | |||||||||||||

| Species | Human | Mouse | |||||||||||

| Entrez | 9369 | 18191 | |||||||||||

| Ensembl | ENSG00000021645 | ENSMUSG00000066392 | |||||||||||

| UniProt | Q9HDB5 | n/a | |||||||||||

| RefSeq (mRNA) | NM_001105250 | NM_172544 | |||||||||||

| RefSeq (protein) | NP_001098720 | NP_766132 | |||||||||||

| Location (UCSC) |

Chr 14: 78.71 – 80.33 Mb |

Chr 12: 89.31 – 90.74 Mb | |||||||||||

| PubMed search | [5] | [6] | |||||||||||

サブファミリー

哺乳類ではニューレキシンは3つの遺伝子(ニューレキシン1、2、3)から成り、プロモーターの違いから、長鎖のαニューレキシン(上流プロモーター)、短鎖のβニューレキシン(下流プロモーター)の2つのアイソフォームに転写される。従って、3つのαニューレキシン(1α、2α、3α)と3つのβニューレキシン(1β、2β、3β)からなる。

さらに、αニューレキシンは選択的スプライシング部位を5つ[alternative splice site (SS)1から5]、βニューレキシンは2つ(SS4と5)有しており、3000以上のスプライス変異体が存在する[11] [1] [12] [13]。特にSS4の選択的スプライシングは神経活動によって、調節されている[14]。

ショウジョウバエや線虫、ミツバチ、アメフラシなどの無脊椎動物においてもαニューレキシン遺伝子が同定されている[13] [15] [16]。また、線虫ではβニューレキシンも同定されている[17]。

構造

αニューレキシンは細胞外側に6つのLNSドメイン[laminin, neurexin, sex-hormone binding protein (LNS)ドメインまたはLaminin G ドメイン]とLNSドメインを隔てる3つの上皮成長因子様ドメイン(epidermal growth factor-like domain)を有している。一方、βニューレキシンのLNSドメインは一つである。両ニューレキシンの細胞内C末端領域にはPDZドメイン[postsynaptic density (PSD) -95/ discs large/ zona-occludens-1ドメイン]結合部位を有する[2] [11](図1)。

βニューレキシン の細胞外構造およびβニューレキシンとニューロリギン複合体の3次元構造が明らかとなっている(動画)[18]。

発現

ニューレキシンは脳に高レベルで発現しており、海馬においては細胞種の違いによって異なるアイソフォームの発現が認められている(例えば、海馬CA1錐体細胞と歯状回顆粒細胞ではニューレキシン3αの発現が認められないのに対して、介在細胞ではニューレキシン3αが高発現している)[19]。また、脳以外の臓器にも発現しており、ニューレキシン1(α, β)と3(α, β)のmRNAは心臓、肺、腎臓、胎盤にも発現している[20] [21]。また、血管においてもニューレキシンの発現が認められている[22]。

| ニューレキシン1 | ニューレキシン2 | ニューレキシン3 |

結合タンパク質

細胞外ドメイン

これまでに5つのタンパク質 [ニューロリギン、dystroglycan、neurexophilins、Leucine-rich repeat transmembrane neuronal proteins (LRRTMs)、Cbln]が同定されている[23] [24] [25] [26] [27] [28] [29] [30] [31] [3]。

ニューロリギンとの結合において、ニューレキシンのスプライス変異体は、細胞間の認識や接着ならびにシナプス構築などの過程に重要な役割を有していることが示されており、現在までにSS4の挿入の有無が結合選択性に影響することが報告されている(ニューロリギンを参照)。

βニューレキシン1(4-)(SS4非挿入体)は、splicing site B(SSB)の挿入の有無に関わらずニューロリギン1[NL1(-), NL1A, NL1B, NL1AB]ならびにニューロリギン2[NL2(-)とNL2A]と高親和性に結合するが、βニューレキシン1(4+)(SS4挿入体)のSSB挿入体ニューロリギン1(NL1B, NL1AB)との結合親和性は低い(表1)[29] [30] [31] [3]。一方、αニューレキシンはSS4の有無に関わらずニューロリギン1-SSB挿入体とは結合しないが[29]、αニューレキシンのLNS6ドメインのみではニューロリギン1-SSB挿入体と結合する[30]。LRRTMsは、α-,βニューレキシン(4-)とのみ結合する[32]。Cbln1とCbln2はα-,βニューレキシン(4+)と結合するが、ニューレキシン(4-)とは結合しない[28]。

Dystroglycanはα-、βニューレキシンとスプライス変異体依存的に結合する[23]。また、neurexophilinはαニューレキシンとスプライス変異体非依存的に結合する[24] [33]。

| αニューレキシン(+SS4) | αニューレキシン(-SS4) | βニューレキシン(+SS4) | βニューレキシン(-SS4) | |

| ニューロリギン1(-) | + | + | +++ | ++++ |

| ニューロリギン1A | + | + | +++ | ++++ |

| ニューロリギン1B | - | - | ++ | ++++ |

| ニューロリギン1AB | - | - | ++ | ++++ |

| ニューロリギン2 | + | + | ++ | ++++ |

| ニューロリギン3 | + | + | + | ++ |

| ニューロリギン4 | + | |||

| Cbln | + | - | + | - |

| LRRTMs | - | + | - | + |

細胞内ドメイン

細胞内C末端領域のPDZドメイン結合部位を介し、シナプトタグミン(synaptotagmin)[36]やCASK[37]などのシナプス前末端局在タンパク質と結合している。

機能

神経

ニューレキシンは主にシナプス前末端に局在し、シナプス後部に局在する結合タンパク質との相互作用によりグルタミン酸作動性(興奮性)およびGABA作動性(抑制性)シナプスの形成・成熟・機能を制御していると考えられている。

ニューレキシンを強制発現させた株化細胞と初代培養神経細胞を共培養することにより、ニューレキシンがシナプス後部の分化に果たす役割が明らかになっている。非神経細胞へのβニューレキシン強制発現は、共培養した神経細胞上の抑制性、興奮性シナプス後部の分化を誘導する。一方、αニューレキシンの強制発現は抑制性シナプス後部の分化を誘導する[38] [4] [39] [31]。βニューレキシン(4+)は、興奮性シナプス後部タンパク質であるニューロリギン1/3/4とPSD-95のクラスター形成能を低下させるが、抑制性シナプス後部タンパク質であるニューロリギン2とgephyrinのクラスター形成能には影響しない[3]。このことから、βニューレキシン のSS4挿入の有無は、興奮性・抑制性神経シナプスの構築の選別に影響すると考えられている。

ニューレキシンとニューロリギンをシナプス前・後細胞にそれぞれ強制発現させた機能解析により、αニューレキシン1とニューロリギン2は機能的抑制性シナプス形成に重要であるが、βニューレキシン1とニューロリギン2の組み合わせは重要ではないことが示唆されている[40]。

以上より、特異的なニューレキシンとニューロリギンの結合の組み合わせが興奮性、抑制性シナプスの仕分けに重要であると考えられている。また、ニューロリギンノックアウトとノックインマウスの解析により、抑制性シナプス前細胞の種類に依存して抑制性シナプスの機能異常が見られることが明らかになっている[41] [42]。これは抑制性細胞の種類によって、発現又は機能しているニューレキシンアイソフォームが異なることを示唆している。

LRRTMはα-, βニューレキシン(4-)と結合し、興奮性シナプス形成を制御している[25]。

αニューレキシンはCa2+チャネルと共にシナプス伝達物質放出機構を調節することが示唆されている[43]。

遺伝子改変マウス

αニューレキシン1 knockoutマウス

- 統合失調症患者で認められるプレパルスインヒビションの低下を示す。海馬において興奮性シナプス伝達障害が認められるが、抑制性シナプス伝達障害はない[44]。αニューレキシン1 ヘテロKOマウスは、新規環境に対する反応性の増加を示し、特に雄性マウスにおいてその行動が認められる[45]。

αニューレキシン triple Knockoutマウス

- 呼吸器系に障害が認められる。KOマウスはGABA作動性神経終末の数を減少させるが、グルタミン酸作動性神経終末には変化を示さない。さらに、KOマウスはCa2+チャネルの機能低下が原因となり、神経伝達物質放出の障害を示すことが報告されている[43]。

血管

βニューレキシンに対する抗体の血管への付加は、血管新生を抑制する。また、ノルアドレナリン誘導血管収縮も減弱させており、血管平滑筋のβニューレキシンはCa2+チャネル調節因子として血管緊張調整に関与している[22] [46]。αニューレキシンの細胞外ドメインの類似断片は、受容体型チロシンキナーゼTie2を介して血管新生を促進する[47]。

腎臓

ニューレキシンは、糸球体足細胞によって得られるスリット膜に発現しており、スリット膜の構成タンパク質であるCD2APと結合している。スリット膜は、糸球体におけるタンパク質通過防止機能を有しており、ニューレキシンはタンパク質尿のバリアー機能に関与すると考えられている[20]。

疾患との関連

自閉症

患者の中にはニューレキシン1と2に変異[ミスセンス変異[5], truncating mutation[6], 一塩基多型[7]]を有するものがいる。

統合失調症

ニューレキシン1での変異 [truncating mutation[6]、コピー数変異[8] [9]] が統合失調症患者で発見されている。

ニューレキシン類似タンパク質

CASPRs(contactin-associated proteins: ニューレキシン4としても知られている)はαニューレキシンと類似の構造を有するが、αニューレキシンには無い細胞外ドメインを有している。ニューレキシンの様に細胞接着分子として機能している[48]。また、CASPR1はAMPA型グルタミン酸受容体の輸送を調節することが報告されている[49]。また、CASPR2の遺伝子変異は自閉症と関連していると考えられている[50]。

関連項目

参考文献

- ↑ 1.0 1.1

Südhof, T.C. (2008).

Neuroligins and neurexins link synaptic function to cognitive disease. Nature, 455(7215), 903-11. [PubMed:18923512] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 2.0 2.1

Craig, A.M., & Kang, Y. (2007).

Neurexin-neuroligin signaling in synapse development. Current opinion in neurobiology, 17(1), 43-52. [PubMed:17275284] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3

Graf, E.R., Kang, Y., Hauner, A.M., & Craig, A.M. (2006).

Structure function and splice site analysis of the synaptogenic activity of the neurexin-1 beta LNS domain. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 26(16), 4256-65. [PubMed:16624946] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 4.0 4.1

Kang, Y., Zhang, X., Dobie, F., Wu, H., & Craig, A.M. (2008).

Induction of GABAergic postsynaptic differentiation by alpha-neurexins. The Journal of biological chemistry, 283(4), 2323-34. [PubMed:18006501] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 5.0 5.1

Feng, J., Schroer, R., Yan, J., Song, W., Yang, C., Bockholt, A., ..., & Sommer, S.S. (2006).

High frequency of neurexin 1beta signal peptide structural variants in patients with autism. Neuroscience letters, 409(1), 10-3. [PubMed:17034946] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2

Gauthier, J., Siddiqui, T.J., Huashan, P., Yokomaku, D., Hamdan, F.F., Champagne, N., ..., & Rouleau, G.A. (2011).

Truncating mutations in NRXN2 and NRXN1 in autism spectrum disorders and schizophrenia. Human genetics, 130(4), 563-73. [PubMed:21424692] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 7.0 7.1

Liu, Y., Hu, Z., Xun, G., Peng, Y., Lu, L., Xu, X., ..., & Xia, K. (2012).

Mutation analysis of the NRXN1 gene in a Chinese autism cohort. Journal of psychiatric research, 46(5), 630-4. [PubMed:22405623] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 8.0 8.1

Ikeda, M., Aleksic, B., Kirov, G., Kinoshita, Y., Yamanouchi, Y., Kitajima, T., ..., & Iwata, N. (2010).

Copy number variation in schizophrenia in the Japanese population. Biological psychiatry, 67(3), 283-6. [PubMed:19880096] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 9.0 9.1

Yue, W., Yang, Y., Zhang, Y., Lu, T., Hu, X., Wang, L., ..., & Zhang, D. (2011).

A case-control association study of NRXN1 polymorphisms with schizophrenia in Chinese Han population. Behavioral and brain functions : BBF, 7, 7. [PubMed:21477380] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Missler, M., & Südhof, T.C. (1998).

Neurexins: three genes and 1001 products. Trends in genetics : TIG, 14(1), 20-6. [PubMed:9448462] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 11.0 11.1

Lisé, M.F., & El-Husseini, A. (2006).

The neuroligin and neurexin families: from structure to function at the synapse. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS, 63(16), 1833-49. [PubMed:16794786] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Baudouin, S., & Scheiffele, P. (2010).

SnapShot: Neuroligin-neurexin complexes. Cell, 141(5), 908, 908.e1. [PubMed:20510934] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 13.0 13.1

Tabuchi, K., & Südhof, T.C. (2002).

Structure and evolution of neurexin genes: insight into the mechanism of alternative splicing. Genomics, 79(6), 849-59. [PubMed:12036300] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Iijima, T., Wu, K., Witte, H., Hanno-Iijima, Y., Glatter, T., Richard, S., & Scheiffele, P. (2011).

SAM68 regulates neuronal activity-dependent alternative splicing of neurexin-1. Cell, 147(7), 1601-14. [PubMed:22196734] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Biswas, S., Russell, R.J., Jackson, C.J., Vidovic, M., Ganeshina, O., Oakeshott, J.G., & Claudianos, C. (2008).

Bridging the synaptic gap: neuroligins and neurexin I in Apis mellifera. PloS one, 3(10), e3542. [PubMed:18974885] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Choi, Y.B., Li, H.L., Kassabov, S.R., Jin, I., Puthanveettil, S.V., Karl, K.A., ..., & Kandel, E.R. (2011).

Neurexin-neuroligin transsynaptic interaction mediates learning-related synaptic remodeling and long-term facilitation in aplysia. Neuron, 70(3), 468-81. [PubMed:21555073] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Haklai-Topper, L., Soutschek, J., Sabanay, H., Scheel, J., Hobert, O., & Peles, E. (2010).

The neurexin superfamily of Caenorhabditis elegans. Gene expression patterns : GEP, 11(1-2), 144-50. [PubMed:21055481] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Araç, D., Boucard, A.A., Ozkan, E., Strop, P., Newell, E., Südhof, T.C., & Brunger, A.T. (2007).

Structures of neuroligin-1 and the neuroligin-1/neurexin-1 beta complex reveal specific protein-protein and protein-Ca2+ interactions. Neuron, 56(6), 992-1003. [PubMed:18093522] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Ullrich, B., Ushkaryov, Y.A., & Südhof, T.C. (1995).

Cartography of neurexins: more than 1000 isoforms generated by alternative splicing and expressed in distinct subsets of neurons. Neuron, 14(3), 497-507. [PubMed:7695896] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 20.0 20.1

Saito, A., Miyauchi, N., Hashimoto, T., Karasawa, T., Han, G.D., Kayaba, M., ..., & Kawachi, H. (2011).

Neurexin-1, a presynaptic adhesion molecule, localizes at the slit diaphragm of the glomerular podocytes in kidneys. American journal of physiology. Regulatory, integrative and comparative physiology, 300(2), R340-8. [PubMed:21048075] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Occhi, G., Rampazzo, A., Beffagna, G., & Antonio Danieli, G. (2002).

Identification and characterization of heart-specific splicing of human neurexin 3 mRNA (NRXN3). Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 298(1), 151-5. [PubMed:12379233] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 22.0 22.1

Bottos, A., Destro, E., Rissone, A., Graziano, S., Cordara, G., Assenzio, B., ..., & Arese, M. (2009).

The synaptic proteins neurexins and neuroligins are widely expressed in the vascular system and contribute to its functions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(49), 20782-7. [PubMed:19926856] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 23.0 23.1

Sugita, S., Saito, F., Tang, J., Satz, J., Campbell, K., & Südhof, T.C. (2001).

A stoichiometric complex of neurexins and dystroglycan in brain. The Journal of cell biology, 154(2), 435-45. [PubMed:11470830] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 24.0 24.1

Petrenko, A.G., Ullrich, B., Missler, M., Krasnoperov, V., Rosahl, T.W., & Südhof, T.C. (1996).

Structure and evolution of neurexophilin. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 16(14), 4360-9. [PubMed:8699246] [WorldCat] - ↑ 25.0 25.1

Ko, J., Fuccillo, M.V., Malenka, R.C., & Südhof, T.C. (2009).

LRRTM2 functions as a neurexin ligand in promoting excitatory synapse formation. Neuron, 64(6), 791-8. [PubMed:20064387] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

de Wit, J., Sylwestrak, E., O'Sullivan, M.L., Otto, S., Tiglio, K., Savas, J.N., ..., & Ghosh, A. (2009).

LRRTM2 interacts with Neurexin1 and regulates excitatory synapse formation. Neuron, 64(6), 799-806. [PubMed:20064388] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Uemura, T., Lee, S.J., Yasumura, M., Takeuchi, T., Yoshida, T., Ra, M., ..., & Mishina, M. (2010).

Trans-synaptic interaction of GluRdelta2 and Neurexin through Cbln1 mediates synapse formation in the cerebellum. Cell, 141(6), 1068-79. [PubMed:20537373] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2

Matsuda, K., & Yuzaki, M. (2011).

Cbln family proteins promote synapse formation by regulating distinct neurexin signaling pathways in various brain regions. The European journal of neuroscience, 33(8), 1447-61. [PubMed:21410790] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3

Boucard, A.A., Chubykin, A.A., Comoletti, D., Taylor, P., & Südhof, T.C. (2005).

A splice code for trans-synaptic cell adhesion mediated by binding of neuroligin 1 to alpha- and beta-neurexins. Neuron, 48(2), 229-36. [PubMed:16242404] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2

Reissner, C., Klose, M., Fairless, R., & Missler, M. (2008).

Mutational analysis of the neurexin/neuroligin complex reveals essential and regulatory components. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(39), 15124-9. [PubMed:18812509] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2

Chih, B., Gollan, L., & Scheiffele, P. (2006).

Alternative splicing controls selective trans-synaptic interactions of the neuroligin-neurexin complex. Neuron, 51(2), 171-8. [PubMed:16846852] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 32.0 32.1

Siddiqui, T.J., Pancaroglu, R., Kang, Y., Rooyakkers, A., & Craig, A.M. (2010).

LRRTMs and neuroligins bind neurexins with a differential code to cooperate in glutamate synapse development. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 30(22), 7495-506. [PubMed:20519524] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Missler, M., Hammer, R.E., & Südhof, T.C. (1998).

Neurexophilin binding to alpha-neurexins. A single LNS domain functions as an independently folding ligand-binding unit. The Journal of biological chemistry, 273(52), 34716-23. [PubMed:9856994] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Koehnke, J., Katsamba, P.S., Ahlsen, G., Bahna, F., Vendome, J., Honig, B., ..., & Jin, X. (2010).

Splice form dependence of beta-neurexin/neuroligin binding interactions. Neuron, 67(1), 61-74. [PubMed:20624592] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Leone, P., Comoletti, D., Ferracci, G., Conrod, S., Garcia, S.U., Taylor, P., ..., & Marchot, P. (2010).

Structural insights into the exquisite selectivity of neurexin/neuroligin synaptic interactions. The EMBO journal, 29(14), 2461-71. [PubMed:20543817] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hata, Y., Davletov, B., Petrenko, A.G., Jahn, R., & Südhof, T.C. (1993).

Interaction of synaptotagmin with the cytoplasmic domains of neurexins. Neuron, 10(2), 307-15. [PubMed:8439414] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Hata, Y., Butz, S., & Südhof, T.C. (1996).

CASK: a novel dlg/PSD95 homolog with an N-terminal calmodulin-dependent protein kinase domain identified by interaction with neurexins. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 16(8), 2488-94. [PubMed:8786425] [WorldCat] - ↑

Graf, E.R., Zhang, X., Jin, S.X., Linhoff, M.W., & Craig, A.M. (2004).

Neurexins induce differentiation of GABA and glutamate postsynaptic specializations via neuroligins. Cell, 119(7), 1013-26. [PubMed:15620359] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Nam, C.I., & Chen, L. (2005).

Postsynaptic assembly induced by neurexin-neuroligin interaction and neurotransmitter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102(17), 6137-42. [PubMed:15837930] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Futai, K., Doty, C.D., Baek, B., Ryu, J., & Sheng, M. (2013).

Specific trans-synaptic interaction with inhibitory interneuronal neurexin underlies differential ability of neuroligins to induce functional inhibitory synapses. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 33(8), 3612-23. [PubMed:23426688] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Gibson, J.R., Huber, K.M., & Südhof, T.C. (2009).

Neuroligin-2 deletion selectively decreases inhibitory synaptic transmission originating from fast-spiking but not from somatostatin-positive interneurons. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 29(44), 13883-97. [PubMed:19889999] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Földy, C., Malenka, R.C., & Südhof, T.C. (2013).

Autism-associated neuroligin-3 mutations commonly disrupt tonic endocannabinoid signaling. Neuron, 78(3), 498-509. [PubMed:23583622] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑ 43.0 43.1

Missler, M., Zhang, W., Rohlmann, A., Kattenstroth, G., Hammer, R.E., Gottmann, K., & Südhof, T.C. (2003).

Alpha-neurexins couple Ca2+ channels to synaptic vesicle exocytosis. Nature, 423(6943), 939-48. [PubMed:12827191] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Etherton, M.R., Blaiss, C.A., Powell, C.M., & Südhof, T.C. (2009).

Mouse neurexin-1alpha deletion causes correlated electrophysiological and behavioral changes consistent with cognitive impairments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106(42), 17998-8003. [PubMed:19822762] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Laarakker, M.C., Reinders, N.R., Bruining, H., Ophoff, R.A., & Kas, M.J. (2012).

Sex-dependent novelty response in neurexin-1α mutant mice. PloS one, 7(2), e31503. [PubMed:22348092] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Bottos, A., Rissone, A., Bussolino, F., & Arese, M. (2011).

Neurexins and neuroligins: synapses look out of the nervous system. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS, 68(16), 2655-66. [PubMed:21394644] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Graziano, S., Marchiò, S., Bussolino, F., & Arese, M. (2013).

A peptide from the extracellular region of the synaptic protein α Neurexin stimulates angiogenesis and the vascular specific tyrosine kinase Tie2. Biochemical and biophysical research communications, 432(4), 574-9. [PubMed:23485462] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Bellen, H.J., Lu, Y., Beckstead, R., & Bhat, M.A. (1998).

Neurexin IV, caspr and paranodin--novel members of the neurexin family: encounters of axons and glia. Trends in neurosciences, 21(10), 444-9. [PubMed:9786343] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Santos, S.D., Iuliano, O., Ribeiro, L., Veran, J., Ferreira, J.S., Rio, P., ..., & Carvalho, A.L. (2012).

Contactin-associated protein 1 (Caspr1) regulates the traffic and synaptic content of α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA)-type glutamate receptors. The Journal of biological chemistry, 287(9), 6868-77. [PubMed:22223644] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI] - ↑

Peñagarikano, O., & Geschwind, D.H. (2012).

What does CNTNAP2 reveal about autism spectrum disorder? Trends in molecular medicine, 18(3), 156-63. [PubMed:22365836] [PMC] [WorldCat] [DOI]